The history of tabletop role-playing games is often dominated by Dungeons & Dragons and companies who hold brand licenses. But there is another company that created not one but three types of new games: Flying Buffalo. In this series we take a look at each of these innovations and how they influenced the game industry. For Flying Buffalo, it all begins with play-by-mail.

[h=3]The Origins of Play-by-Mail[/h]Playing games with another player at a distance have been in existence for as long as there was communication between two parties. Correspondence chess -- in which chess players send each others' moves on a board they replicate at each location -- has been around for centuries. Diplomacy was the only multiplayer play-by-mail game with a referee that was regularly moderated, but not as a business, since the 1960s. But it wasn't until Flying Buffalo got started that play-by-mail games were moderated by computers, allowing considerably more complex games to be played out.

Founder Rick Loomis was frustrated playing games like Diplomacy, particularly with how it related to "fog of war" -- keeping players in the dark about each others' locations. So he mad up a new one:

While serving in the Army, Loomis came up with his answer to the first problem by removing the requirement for a referee:

The second and third issues were finally tackled by the advent of new technology: Computers.

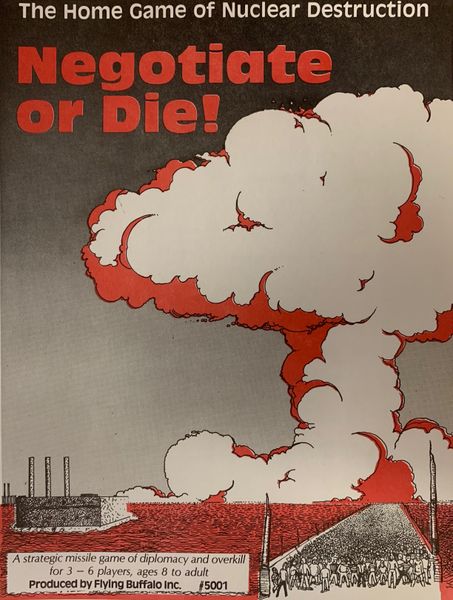

[h=3]The Computer Revolution[/h]With his new game in hand, Loomis mailed postcards to the play-by-mail ads in Avalon Hill's The General magazine. He soon found that his Nuclear Destruction game had over 200 players in it.

Back then, using a computer for play-by-mail was revolutionary, as described by Jon Peterson in Playing at the World:

Other companies soon joined in the fun:

[h=3]The Buffalo Takes Off[/h]Loomis considered incorporating the word "Simulations" into the title of his new company at first, as he described in Flying Buffalo Quarterly #79:

[h=3]The RPG Legacy of PBM[/h]Play-by-mail has several advantages unique to the form: it offers a ready supply of opponents, is easier to schedule due to the asynchronous nature of each turn, and can handle more players than a tabletop game over the span of several years. And yet, it's entirely possible to play a role-playing game in the PBM format, albeit at a much slower pace.

Flying Buffalo was keenly aware of the popularity of Dungeons & Dragons and its impact on play-by-mail. The opportunities seemed endless and, for the right company, potentially lucrative. It turns out that there was a demand for play-by-mail role-playing games, but not everyone was up to the challenge:

Play-by-mail continues on in a wide variety of formats, with the "mail" replaced by web, email, or even browser-based social games that take place on Twitter:

The role-playing game revolution was not lost on Loomis. In the next installment we'll look at Flying Buffalo's tabletop RPG innovation...a D&D-inspired game titled Tunnels & Trolls.

Founder Rick Loomis was frustrated playing games like Diplomacy, particularly with how it related to "fog of war" -- keeping players in the dark about each others' locations. So he mad up a new one:

In high school, I invented a multi-player wargame with hidden movement that was a lot of fun, but had a couple of serious problems. (1) no one else wanted to do all the work of refereeing it (so I hardly ever got to play, since I had to be the referee) (2) it took a long time to play, as the players turned in their moves one at a time so the referee could calculate the results of all his moves and attacks, before sending the next player his turn and (3) if there were more countries in the game than I could find players for, what did we do with the extra countries?

For the problem of unplayed countries, I came up with the idea of the "popularity index" where each player would have an "index" in all the non-played countries. You could raise your "index" by actions in the game such as giving money to the non-player, and the player with the highest "index" on a given turn could give orders to the non-played country. Since all my friends who used to play my complicated games in high school were scattered who-knows-where by now, I invented a simpler game (Nuclear Destruction) that made use of these indexes, so I could see how it worked.

[h=3]The Computer Revolution[/h]With his new game in hand, Loomis mailed postcards to the play-by-mail ads in Avalon Hill's The General magazine. He soon found that his Nuclear Destruction game had over 200 players in it.

I met my friend Steve MacGregor and he agreed to write a computer program for my new game. We rented time on a CDC 3300 computer that wasn't far from Fort Shafter. (In Hawaii. One might wonder why I was wasting time with computers instead of hanging out on the beach watching babes in bikinis, but I really wanted to be able to play these games myself and if the computer did the moderating, I could play too!) Plus we could use simultaneous movement with the computer keeping track of everything, and that would speed the games up enormously.

While individual hobbyists could not afford their own computers in the early 1970s, one hobbyist built a business on multi-commander play-by-mail games administered by a minicomputer: Rick Loomis of Flying Buffalo. His Nuclear Destruction (1970), a simulation of international nuclear stockpiling, diplomacy and conflict, inspired many other for-profit postal wargames ( typically costing a fee of around twenty-five cents per turn); a critical selling point, as an advertisement in the January 1974 American Wargamer touted, was that these “games are moderated by a fair and impartial Raytheon 704 computer.” Aside from primitive games like Pong, this was as close as a gamer could come to playing on a computer in the early 1970s.

Other companies soon joined in the fun:

Loomis witnessed the rise of an entire industry. Many of those companies failed; in his article, Loomis discusses the challenges of running a PBM company:The typical PBM game uses a system of turns. Each turn corresponds to one "move" by all players, so if you use the chess analogy, sending a move to an opponent and getting his reponse would be one "turn." However, with PBM games you generally don't send moves directly to your opponent. Instead, the PBM company (in this case Agents of Gaming, or AOG) acts as a mediator, resolving your moves and sending you reports of what happened as a result...During each turn, you send in a report to the moderator, who enters it into the computer, "runs" the turn, prints out your report and sends it to you. For most games, this happens over a two-week period (though one- or three-week schedules are available for some variants). Each such turn costs a "turn fee," which varies depending on the PBM company, the complexity of the game, the size and intricacy of the reports and orders, and other factors.

Loomis uses the slogan "We Created the Play By Mail Industry" because he stakes his claim on being the first person to run a play-by-mail server as a full-time job. Built on that success, Flying Buffalo was incorporated in 1972.It sounds so easy: get a personal computer, write a program to run your game, put an ad in a few magazines, then sit back and let your computer do all the work while you bank a few extra bucks each week. Unfortunately there are so many problems that are not initially apparent: program bugs, equipment breakdowns, answering rules questions, answering complaints, [see the letter to the editor in this issue of FBQ] opening letters, entering moves into the computer, correcting mistakes [both mistakes that YOU made, and mistakes that the customer made], moves that arrive late, moves that have unreadable game numbers or return addresses, keeping track of how much money everyone owes, deciding what to do about someone who hasn’t paid the money he owes but is still sending in game turns [here at FBI we “write off” $2000 to $4000 a year in accounts of people who were allowed to go ‘a little bit’ negative, and then ended up quitting without ever paying us], handling bounced checks, and on and on. It is easy for a newcomer to get swamped, and then there is a tendancy to put everything off.

[h=3]The Buffalo Takes Off[/h]Loomis considered incorporating the word "Simulations" into the title of his new company at first, as he described in Flying Buffalo Quarterly #79:

Computers continued to influence the development of play-by-mail games with the spread of new communication channels, particularly the Internet:Most of the game companies, clubs, organizations, or magazines which I knew about either had the word “Simulations” or some kind of German word in their title, representing the interest among adolescent male wargamers in WWII Germany (Panzerfaust magazine, International Kriegspiel Society, games called Kriegspiel, Panzerblitz, and Blitzkrieg, etc.) I considered naming my company something like “SImulated Simulations, Inc” or “Kriegblitzpanzerspiel Inc” but instead decided to get something more distinctive. I actually coined the “Flying Buffalo” title as the name of the stamp and coin shop I was going to start when I got out of the army. (From Flying Eagle pennies and Buffalo nickels - Rick’s Coin Shop is so boring!) Steve and I started using that name for fun, but soon discovered that it made us very distinctive. When I went to the computer center to pick up our run for the day, the clerk at the window didn’t have to go look us up to see whether it had been done yet. He knew as soon as I mentioned our name whether it was done, and where it was.

Play by mail gaming shares many similarities with board gaming, as well, the turn based aspect a signature feature of many PBM games. Unlike many modern-day massively multiplayer online games of various types, postal games tended - and still tend - to deliver a more personalized gaming experience, one that did not leave the player lost in a tsunami of player pools that number in the millions, for some of the more heavily populated massively multiplayer online games, particularly where MMORPGs of note are concerned. Combining a beer & pretzels sort of appeal with a community of both commercial and non-commercial game moderators, PBM left an indelible mark upon the history of gaming. Rich gaming experiences that were unique to postal gaming helped elevate the hobby and the industry to such a place in the public eye that good old correspondence gaming soon carved out a place for itself in the pantheon of gaming genres.

Flying Buffalo was keenly aware of the popularity of Dungeons & Dragons and its impact on play-by-mail. The opportunities seemed endless and, for the right company, potentially lucrative. It turns out that there was a demand for play-by-mail role-playing games, but not everyone was up to the challenge:

.I suppose the most notorious of the “disappearing pbm companies” was Lords of Valetia. This was announced via a flyer and then a full page ad in Strategy and Tactics magazine. It was a hand-run, fantasy role-playing game announced just as D&D was getting popular. I understand that he immediately got 1000 players and was swamped. Unfortunately, it was run by one college student, entirely by hand. There was a long delay and then another group announced they had taken it over. They actually ran several turns for many people. (Mike Stackpole says he got five or six turns). Then they ran into trouble also, and a fellow named Elmer Hinton, who called himself “Gamemasters Publishers Association” offered to take it over. They eagerly handed it over to him, and he published several newsletters and took out many full page ads in magazines like The Space Gamer and The Dragon. Unfortunately I’m not sure whether anyone actually got any turns from Elmer. He was going to put the whole thing on a computer, and had lots of other grandiose plans that never quite got anywhere

Whether one says PBM, PBM games, PBM gaming, play by mail, play-by-mail, postal games, postal gaming, play by post, correspondence games, or correspondence gaming, they are all variations on the exact, same thing. Later (as in newer or more recent) variations on the core genre that is postal gaming have manifested themselves as PBeM (play by e-mail), PBM (play by web - as in the World Wide Web), PBI (play by Internet), TBG (turn based gaming), and even BBG (browser based games).

SaveSave

Last edited: