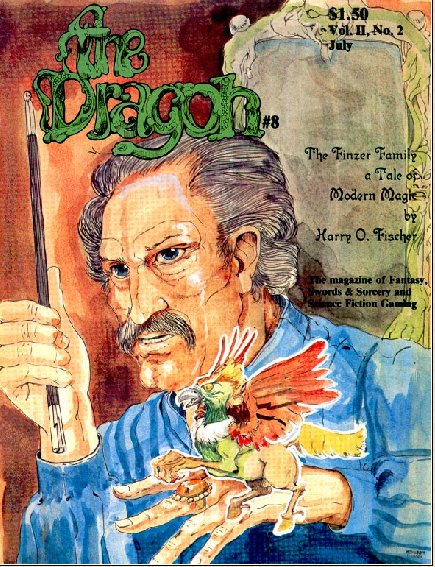

The Dragon Issue 8 was published in July 1977. It is 32 pages long, with a cover price of $1.50. In this issue, Gygax massively expands the world of Dungeons & Dragons.

Tim Kask's editorial is all about fiction, which is one aspect of the magazine he loved. He is pleased to present a lengthy story by Harry O. Fischer called "The Finzer Family." Fischer was a college friend of Fritz Leiber, and together they created the world of Nehwon, and the city of Lankhmar, as a backdrop for their war games.

Leiber, of course, went on to become one of the fathers of the sword and sorcery genre, writing a whole string of stories about Lankhmar featuring his characters Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Fischer was much less prolific, and "The Finzer Family" is one of only two stories he ever published.

James Ward returns this issue, with additional material for Metamorphosis Alpha. More importantly, he shares a one-page sneak preview of a new game called Gamma World. This post-apocalyptic science fantasy RPG would be published a few months later, and TSR would abandon Metamorphosis Alpha as a result.

This issue also has a comprehensive article about designing towns and villages in D&D, and Rob Kuntz describes a realistic method of valuing gems and jewellery. These articles are fun stuff for those who like a lot of detail in their campaigns.

By far the most important article is "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D" by Gary Gygax. Here, Gygax defines the cosmology that has underpinned Dungeons & Dragons down to the present day.

The idea of planes (defined as different realities or alternate dimensions) has long been a trope in fantasy fiction, and Gygax's conception of them seems to have been heavily influenced by writer Michael Moorcock. The planes were briefly mentioned in the original D&D rules with a spell called "Contact Higher Planes." The planes were not named or described there, though, simply given a number. The first time a plane is named is in the Greyhawk supplement for OD&D, which mentions the "astral plane" in relation to the aptly named "Astral Spell."

Gygax hints at the planes again in The Strategic Review #6, in an article that lays out his two-axis alignment system (Good vs. Evil, Law vs. Chaos) for the first time. It includes a diagram that matches several metaphysical locations (Heaven, Paradise, Elysium, Limbo, the Abyss, Hades, Hell, and Nirvana) to a position on his alignment graph. But the article gives no further information about these places.

This brings us to the article in The Dragon #8, in which Gygax states:

It is striking to see how much of this cosmology has survived to the present day. The accompanying graphic is essentially the "great wheel" representation of the planes that has since become standard, with the prime material plane at the center surrounded by inner and outer planes. There is a co-existent ethereal plane and also an astral plane that ties the inner and outer planes together. There are sixteen outer planes, and most of their names are the same as the modern names (or are related).

The fact that we are still adventuring in essentially the same multiverse over forty years later shows me what an elegant, evocative, and clever piece of game design this is. It also speaks volumes about Gygax's design sensibilities and the greatness of his vision for the game. In my view, this is one of the most important articles ever published in the magazine.

Next issue sees the introduction of one of D&D's most beloved characters—and the strange story of the man who created him.

This article was contributed by M.T. Black as part of EN World's Columnist (ENWC) program.M.T. Black is a game designer and DMs Guild Adept. Please follow him on Twitter @mtblack2567 and sign up to his mailing list. We are always on the lookout for freelance columnists! If you have a pitch, please contact us!

Tim Kask's editorial is all about fiction, which is one aspect of the magazine he loved. He is pleased to present a lengthy story by Harry O. Fischer called "The Finzer Family." Fischer was a college friend of Fritz Leiber, and together they created the world of Nehwon, and the city of Lankhmar, as a backdrop for their war games.

Leiber, of course, went on to become one of the fathers of the sword and sorcery genre, writing a whole string of stories about Lankhmar featuring his characters Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Fischer was much less prolific, and "The Finzer Family" is one of only two stories he ever published.

James Ward returns this issue, with additional material for Metamorphosis Alpha. More importantly, he shares a one-page sneak preview of a new game called Gamma World. This post-apocalyptic science fantasy RPG would be published a few months later, and TSR would abandon Metamorphosis Alpha as a result.

This issue also has a comprehensive article about designing towns and villages in D&D, and Rob Kuntz describes a realistic method of valuing gems and jewellery. These articles are fun stuff for those who like a lot of detail in their campaigns.

By far the most important article is "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D" by Gary Gygax. Here, Gygax defines the cosmology that has underpinned Dungeons & Dragons down to the present day.

The idea of planes (defined as different realities or alternate dimensions) has long been a trope in fantasy fiction, and Gygax's conception of them seems to have been heavily influenced by writer Michael Moorcock. The planes were briefly mentioned in the original D&D rules with a spell called "Contact Higher Planes." The planes were not named or described there, though, simply given a number. The first time a plane is named is in the Greyhawk supplement for OD&D, which mentions the "astral plane" in relation to the aptly named "Astral Spell."

Gygax hints at the planes again in The Strategic Review #6, in an article that lays out his two-axis alignment system (Good vs. Evil, Law vs. Chaos) for the first time. It includes a diagram that matches several metaphysical locations (Heaven, Paradise, Elysium, Limbo, the Abyss, Hades, Hell, and Nirvana) to a position on his alignment graph. But the article gives no further information about these places.

This brings us to the article in The Dragon #8, in which Gygax states:

"For game purposes the DM is to assume the existence of an infinite number of co-existing planes. The normal plane for human-type life forms is the Prime Material Plane. A number of planes actually touch this one and are reached with relative ease. These planes are the Negative and Positive Material Planes, the Elemental Planes (air, earth, fire, water), the Etherial Plane (which co-exists in exactly the same space as the Prime Material Plane), and the Astral Plane (which warps the dimension we know as length [distance]). Typical higher planes are the Seven Heavens, the Twin Paradises, and Elysium. The plane of ultimate Law is Nirvana, while the plane of ultimate Chaos (entropy) is Limbo. Typical lower planes are the Nine Hells, Hades’ three glooms, and the 666 layers of the Abyss."

It is striking to see how much of this cosmology has survived to the present day. The accompanying graphic is essentially the "great wheel" representation of the planes that has since become standard, with the prime material plane at the center surrounded by inner and outer planes. There is a co-existent ethereal plane and also an astral plane that ties the inner and outer planes together. There are sixteen outer planes, and most of their names are the same as the modern names (or are related).

The fact that we are still adventuring in essentially the same multiverse over forty years later shows me what an elegant, evocative, and clever piece of game design this is. It also speaks volumes about Gygax's design sensibilities and the greatness of his vision for the game. In my view, this is one of the most important articles ever published in the magazine.

Next issue sees the introduction of one of D&D's most beloved characters—and the strange story of the man who created him.

This article was contributed by M.T. Black as part of EN World's Columnist (ENWC) program.M.T. Black is a game designer and DMs Guild Adept. Please follow him on Twitter @mtblack2567 and sign up to his mailing list. We are always on the lookout for freelance columnists! If you have a pitch, please contact us!