freyar

Extradimensional Explorer

Well, we can actually go back to Neptune's discovery in the 1840s. That was based on deviations of Uranus's orbit compared to what it would have been just from orbiting the sun (and the influences of the inner planets). That's a fairly simple system: you're looking mostly at the influence of one planet (Neptune) on one other (Uranus). So the predicted location of Neptune was pretty precise. (I didn't know this before, but apparently Galileo spotted Neptune in an early telescope but probably couldn't have measured its motion compared to background stars.)

Pluto's discovery was also based on deviations of Uranus's orbit from what you'd expect after including the effects of Neptune. So that problem is harder, since you have to account for two planets (Neptune and Pluto) acting on Uranus. So I believe the predicted position for Pluto was a lot less precise. Combined with the fact that Pluto is pretty dim made it a lot harder to find Pluto.

What we have in the present case is some unexplained behavior of a lot of Kuiper belt objects. (Pluto and Sedna are dwarf planets and also large Kuiper belt objects.) Apparently, a lot of these are clustered in their orbits, and it's not known why. The two planet hunters have done a lot of simulations of what would happen if you took an initially uniform Kuiper belt full of planetoids and also had a big planet orbiting through it. What they say is that a planet with 10x the earth's mass and a certain orbit (and currently near the far point of its orbit) can explain this clustering (and do a better job than previous hypotheses). So you can see that this is a much harder problem than finding Pluto: you have to look at the effects on lots of objects, you don't know exactly what else is out there, and you have to assume the big planet is the biggest effect. Then you have to add in the fact that the objects you've measured haven't actually been discovered that long ago, so you haven't mapped much of their orbits. So I don't think the prediction is terribly precise, and it's pretty dim, too.

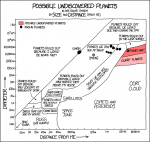

Here is a brief commentary on why finding this thing is hard.

Pluto's discovery was also based on deviations of Uranus's orbit from what you'd expect after including the effects of Neptune. So that problem is harder, since you have to account for two planets (Neptune and Pluto) acting on Uranus. So I believe the predicted position for Pluto was a lot less precise. Combined with the fact that Pluto is pretty dim made it a lot harder to find Pluto.

What we have in the present case is some unexplained behavior of a lot of Kuiper belt objects. (Pluto and Sedna are dwarf planets and also large Kuiper belt objects.) Apparently, a lot of these are clustered in their orbits, and it's not known why. The two planet hunters have done a lot of simulations of what would happen if you took an initially uniform Kuiper belt full of planetoids and also had a big planet orbiting through it. What they say is that a planet with 10x the earth's mass and a certain orbit (and currently near the far point of its orbit) can explain this clustering (and do a better job than previous hypotheses). So you can see that this is a much harder problem than finding Pluto: you have to look at the effects on lots of objects, you don't know exactly what else is out there, and you have to assume the big planet is the biggest effect. Then you have to add in the fact that the objects you've measured haven't actually been discovered that long ago, so you haven't mapped much of their orbits. So I don't think the prediction is terribly precise, and it's pretty dim, too.

Here is a brief commentary on why finding this thing is hard.