ThorinTeague

Creative/Father/Professor

Heath's Geekverse recently did a video on this, and I had an old writing that has been sitting on the backburner that I thought I'd share for comment and constructive criticism.

Here is a link to the second post.

Here is a TL;DR summary:

A man named Joseph Campbell studied mythological hero stories from around the world and published a book asserting that all these stories have certain traits in common. This book is called “The Hero With 1000 Faces.” He believed in a “monomyth,” meaning that each hero story can be thought of as a retelling of the same myth. In narratology and comparative mythology, the monomyth, or the hero’s journey, is the common template of a broad category of tales and lore that involves a hero who goes on an adventure, and in a decisive crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed. When applied with judgment, wisdom, and flexibility, the Hero’s journey concepts are widely agreed to add unparalleled depth and resonance to your Hero story.

I have watched well meaning but ultimately self-important academics [read: irony] try to pigeonhole many stories into this framework for which it is not appropriate (for example, The Big Lebowski─preposterous!) I’m going to tell you, and this will run contrary to what some would say, that the Hero’s Journey monomyth simply doesn’t work for everything. But it’s perfect for hero mythologies and adventure stories, so for us, it is going to be extremely valuable.

Let us now explore this notion that all hero stories are interconnected by a few universal structural elements we can find in mythology, movies, novels, and epic poetry. I’m going to give here a condensed version of the Hero’s Journey monomythical structure and do my best to keep it easily relatable to playing RPG’s.

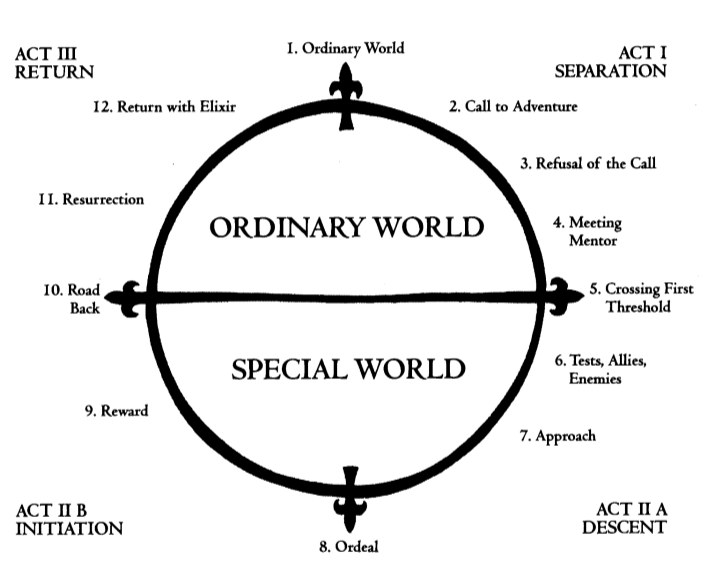

The hero’s journey is like a cycle. It begins and ends in the hero’s ordinary world, but in between it passes through some extraordinary, sometimes magical places. The version I am presenting here is slightly altered by Christian Vogler as written in “The Writer’s Journey,” which he wrote for writers. I feel Vogler’s approach applies more directly, is more accessible than Campbell, and I will be leaning the Vogler text a bit more for citations in this section. With storytelling, and more so with RPG’s, you should not feel constrained by this structure. Moving or removing plot points, changing anything, or ignoring this structure entirely is fine.

Image Credit: Lewis Jorstad at thenovelsmithy.com

Also, this could be either a micro or macro framework--or both. That is to say, the hero(s) can go through this cycle in one adventure, as well as throughout the course of a full length campaign that runs from level one to character retirement.

Spoilers ahead: I’m about to ruin every Disney/adventure/scifi film ever made, book written, or story told, anywhere, ever. Vogler was a close advisor to Disney and crew, and his notes that circulated as memos throughout Disney, which they treat as gospel, became the basis for The Writer’s Journey.

The first important detail is that the Hero is reluctant. The hero has to be pushed out of the ordinary world. She or he should be happy and comfortable at their home (referred to in the cycle as “the ordinary world”). The ordinary world in which we begin is a place called “home” to the hero. It is a comfortable and familiar place for the main character, who is about to be the fish-out-of-water. Salvatore turned the ordinary world on its ear for Drizzt Do’Urden, who left his violent and chaotic underground home of Menzoberranzan for the (to him) alien and hostile surface world.

Then, something happens that forces them to action. This is also called a “hook.” The PC’s may or may not “bite the hook,” that is up to them. The hero in a monomyth does not always immediately bite the hook (the next step is called Refusal of the Call). The hero is presented with a problem, a job, a proposition, a cry for help, or any number of calls. This can take many forms in a campaign. Something is out of balance with the “universe,” figuratively or literally, and the quintessential princess must be rescued and returned for balance to be restored. Could be as simple as getting hired, conscripted to an army, or as epic as losing their family to a goblin raid. In revenge stories, there is a wrong that must be righted or avenged. Gathering allies begins if it has not already begun. After this point, the hero can no longer remain in the ordinary world.

The Call establishes what’s at stake for the hero and her or his ordinary world. The stakes could be expressed in the form of a question: Will Rowyn survive? How can the princess be rescued? Why has there been an unending storm blotting out the sun and how do we restore sunlight?

The archetypical hero of every myth is an initiate being introduced to the mysteries of life, the universe, and death. The hero’s experience will change them forever.

While a key part of the monomyth, PC’s are not obligated to refuse the call to adventure, and shouldn’t force the PC to make one choice or another. But for completeness sake, the hero will refuse the call to action at this point in the adventure for any number of reasons. Refusal is ultimately about fear. Feelings of inadequacy, obligations preventing her or him from accepting the call, fear, or any other number of internal stonewalling factors creating an obstacle between the hero and the call to action. Sometimes outside influence is required to spur the hero into committing at last to action. This influence can take the form of further harm to the ordinary world or something or someone the hero cares about, putting the natural balance in even further disarray, or the encouragement of a mentor figure. These obstacles will have to be overcome, but not without help. Which brings us to...

The hero’s mentor is an elderly parent figure that will give advice and gifts, and generally prepare the hero for their journey. This character in these types of stories is traditionally a wizard (literally or essentially). The character is protective of the hero and prepares the hero to face the unknown by providing gifts, advice, and sometimes magical aid. This character (the most common supporting character) in mythology represents the relationship between parent and child, or God and man. It is a nurturing and caring figure, concerned for the well being of the hero but also wise with the knowledge that the hero must begin, and ultimately complete, her or his own journey.

This is the moment of departure for the adventure. At this point, the hero crosses over into a world outside of, and completely alien to, their home. Our hero has entered the outside world for the first time. In this magical world the majority of the action of acts 2 and 3 take place. The rules, parameters, inhabitants, and limits of the world beyond this threshold are all unknown. This is a likely milestone for the hero to meet the threshold guardian or gatekeeper. The gatekeeper can take many forms, and does not necessarily need to be killed--or even defeated. But the hero does need to get past him or her, whether the gatekeeper is willing or not. Heimdall is a quintessential gatekeeper, and a perfect example.

The hero will now begin learning about the outside world by being tested for worthiness to continue, as the road ahead is perilous and not for the faint of heart. It is common for the hero in these stories to fail one or more of these tests. It is archetypical for tests to come in threes. Any final allies the hero may need to add to the group will be procured by this stage.

Taverns, inns, saloons, and other gathering places for adventurers are a great place for this stage. They are useful for the hero to gather information about the world and their mission, and both enemies and allies may be found at such places.

The hero, nearing the center of the story and the special magical world, experiences full and final separation from her or his known world and idea of self. Entering this stage of the journey is analogous to undergoing change. This stage can and often does involve enemies, dangers, grief, or other such setbacks. It is also a stage of discovery and power.

The hero will now prepare and at last journey into the inner sanctum of the enemy, the unknown, or whatever form the antagonist has taken. Crossing this threshold and entering the lair is another key part of the monomyth. Many of these throughout human history used underground settings, such as the Labyrinth and the Abyss.

The hero faces the greatest challenge yet. The hero often meets the villain in this stage if she or he hasn’t already. The hero has the proverbial “darkest hour,” where she or he will face death and come back from the brink. The audience (players) will be in the most suspense, not knowing if their heroes will live or die.

This critical moment in the hero’s journey should be an emotional rollercoaster. This moment requires the hero to die, literally or figuratively, so that she or he can come back again. This is a huge source of energy and punch for the monomyth, and one of the primary driving engines that makes it work and makes it resonate so profoundly with most if not all people.The experiences of the lead up stages have brought us (or should have brought us) to identify, empathize, and invest in the character. The GM and players are now made to experience the brink-of-death moment right along with the hero, and if the storyteller has done a good job, the experience will confer the utmost concern and anxiety to all interested parties. That’s why the investment is so crucial. This is where everything either comes together, or falls apart.

The hero has survived death, slain the BBEG, and “seized the elixir” (the reward). Players and GM now have cause to celebrate. This is the appropriate point in the monomyth and in any sensible fantasy adventure for the hero to take possession of the reward of the story, be it monetary, material, spiritual, knowledge, magic, or anything else. The hero has risked or sacrificed her or his life on behalf of the community in the ordinary world, and truly earned the title of “hero.”

The hero may not be safe just yet. Sometimes, the BBEG is not killed in The Ordeal, and will be in hot pursuit during The Road Back. Some of the greatest chase scenes come in this phase.

The magical special world is being left behind, but the hero is now forever changed.

The ancient warriors returned to the village with blood on their hands and had to purify themselves before returning to their people. Having faced and overcome the ordeal, the hero comes back, reborn (figuratively or literally in the case of Fantasy RPG’s), having been fully purified and ready to reenter the ordinary world (go home).

The hero receives the final reward for defeating the "BBEG," and (again, in the archetypical mythical structure), returns with this gift to improve her or his ordinary world. The journey is meaningless without a reward to bring back. The reward can be experience or knowledge, too. But ultimately this elixir has the power to heal and restore balance to the universe.

The Hero’s Journey is an approximate framework that should guide but not railroad your adventure. Within this framework there should be room for surprises, unexpected decisions, and room for the story to grow organically from player choices. Feel free to experiment with moving or omitting some of these plot points to see how that affects the feel of the adventure.

My philosophy and feelings on roleplaying are that it is a story and a creative outlet as well as a game. An invulnerable (or more often, near or functionally invulnerable) character is not one that participants are as likely to attach to in a story, because most people cannot relate. A character that has weaknesses and uniqueness is more likely to garner an emotional response from the audience.

We are required to get emotionally attached to the characters to have a story. When a participant in a story says, “Gee, I hope my favorite character escapes this danger!”, and that character is up against something that appears more powerful, insurmountable, and so on, tension is created. This dramatic tension is the engine that drives every great hero story—no exceptions.

If that character is superpowered, or in some way seems unkillable, the tension falls like a house of cards. Without the tension, there is no story. Without the tension, there is no adventure or risk. Without any real risk, the rewards are mere participation trophies; the conclusion is foregone; the reward is inevitable. This is something I hope to avoid in many aspects throughout the game, as it is often a campaign killer, or requires some heavy-handed and cheap-feeling contrivance to reduce the players’ equipment or power in order to allow the story to continue.

Here is a link to the second post.

Here is a TL;DR summary:

- The hero's journey has a formulaic narrative structure that can we can profit from by applying it to our heroic fantasy RPG's.

- The hero's journey requires flawed, imperfect, [semi/demi]human heroes that we can empathize and identify with.

- The hero's journey is divided into the standard 3 acts of traditional narrative.

- Each act contains 2-4 standard story beats.

- This formula does not need to be constraining (or used at all) but it is known to be extremely effective.

The Hero's Journey Monomythical Story Arc

A man named Joseph Campbell studied mythological hero stories from around the world and published a book asserting that all these stories have certain traits in common. This book is called “The Hero With 1000 Faces.” He believed in a “monomyth,” meaning that each hero story can be thought of as a retelling of the same myth. In narratology and comparative mythology, the monomyth, or the hero’s journey, is the common template of a broad category of tales and lore that involves a hero who goes on an adventure, and in a decisive crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed. When applied with judgment, wisdom, and flexibility, the Hero’s journey concepts are widely agreed to add unparalleled depth and resonance to your Hero story.

I have watched well meaning but ultimately self-important academics [read: irony] try to pigeonhole many stories into this framework for which it is not appropriate (for example, The Big Lebowski─preposterous!) I’m going to tell you, and this will run contrary to what some would say, that the Hero’s Journey monomyth simply doesn’t work for everything. But it’s perfect for hero mythologies and adventure stories, so for us, it is going to be extremely valuable.

Let us now explore this notion that all hero stories are interconnected by a few universal structural elements we can find in mythology, movies, novels, and epic poetry. I’m going to give here a condensed version of the Hero’s Journey monomythical structure and do my best to keep it easily relatable to playing RPG’s.

The hero’s journey is like a cycle. It begins and ends in the hero’s ordinary world, but in between it passes through some extraordinary, sometimes magical places. The version I am presenting here is slightly altered by Christian Vogler as written in “The Writer’s Journey,” which he wrote for writers. I feel Vogler’s approach applies more directly, is more accessible than Campbell, and I will be leaning the Vogler text a bit more for citations in this section. With storytelling, and more so with RPG’s, you should not feel constrained by this structure. Moving or removing plot points, changing anything, or ignoring this structure entirely is fine.

Image Credit: Lewis Jorstad at thenovelsmithy.com

Also, this could be either a micro or macro framework--or both. That is to say, the hero(s) can go through this cycle in one adventure, as well as throughout the course of a full length campaign that runs from level one to character retirement.

Spoilers ahead: I’m about to ruin every Disney/adventure/scifi film ever made, book written, or story told, anywhere, ever. Vogler was a close advisor to Disney and crew, and his notes that circulated as memos throughout Disney, which they treat as gospel, became the basis for The Writer’s Journey.

ACT I

The Ordinary World

The first important detail is that the Hero is reluctant. The hero has to be pushed out of the ordinary world. She or he should be happy and comfortable at their home (referred to in the cycle as “the ordinary world”). The ordinary world in which we begin is a place called “home” to the hero. It is a comfortable and familiar place for the main character, who is about to be the fish-out-of-water. Salvatore turned the ordinary world on its ear for Drizzt Do’Urden, who left his violent and chaotic underground home of Menzoberranzan for the (to him) alien and hostile surface world.

The Call to Adventure (AKA Hook)

Then, something happens that forces them to action. This is also called a “hook.” The PC’s may or may not “bite the hook,” that is up to them. The hero in a monomyth does not always immediately bite the hook (the next step is called Refusal of the Call). The hero is presented with a problem, a job, a proposition, a cry for help, or any number of calls. This can take many forms in a campaign. Something is out of balance with the “universe,” figuratively or literally, and the quintessential princess must be rescued and returned for balance to be restored. Could be as simple as getting hired, conscripted to an army, or as epic as losing their family to a goblin raid. In revenge stories, there is a wrong that must be righted or avenged. Gathering allies begins if it has not already begun. After this point, the hero can no longer remain in the ordinary world.

The Call establishes what’s at stake for the hero and her or his ordinary world. The stakes could be expressed in the form of a question: Will Rowyn survive? How can the princess be rescued? Why has there been an unending storm blotting out the sun and how do we restore sunlight?

The archetypical hero of every myth is an initiate being introduced to the mysteries of life, the universe, and death. The hero’s experience will change them forever.

Refusal of the Call

While a key part of the monomyth, PC’s are not obligated to refuse the call to adventure, and shouldn’t force the PC to make one choice or another. But for completeness sake, the hero will refuse the call to action at this point in the adventure for any number of reasons. Refusal is ultimately about fear. Feelings of inadequacy, obligations preventing her or him from accepting the call, fear, or any other number of internal stonewalling factors creating an obstacle between the hero and the call to action. Sometimes outside influence is required to spur the hero into committing at last to action. This influence can take the form of further harm to the ordinary world or something or someone the hero cares about, putting the natural balance in even further disarray, or the encouragement of a mentor figure. These obstacles will have to be overcome, but not without help. Which brings us to...

Meeting with the Mentor

The hero’s mentor is an elderly parent figure that will give advice and gifts, and generally prepare the hero for their journey. This character in these types of stories is traditionally a wizard (literally or essentially). The character is protective of the hero and prepares the hero to face the unknown by providing gifts, advice, and sometimes magical aid. This character (the most common supporting character) in mythology represents the relationship between parent and child, or God and man. It is a nurturing and caring figure, concerned for the well being of the hero but also wise with the knowledge that the hero must begin, and ultimately complete, her or his own journey.

ACT II

Crossing the First Threshold

This is the moment of departure for the adventure. At this point, the hero crosses over into a world outside of, and completely alien to, their home. Our hero has entered the outside world for the first time. In this magical world the majority of the action of acts 2 and 3 take place. The rules, parameters, inhabitants, and limits of the world beyond this threshold are all unknown. This is a likely milestone for the hero to meet the threshold guardian or gatekeeper. The gatekeeper can take many forms, and does not necessarily need to be killed--or even defeated. But the hero does need to get past him or her, whether the gatekeeper is willing or not. Heimdall is a quintessential gatekeeper, and a perfect example.

Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The hero will now begin learning about the outside world by being tested for worthiness to continue, as the road ahead is perilous and not for the faint of heart. It is common for the hero in these stories to fail one or more of these tests. It is archetypical for tests to come in threes. Any final allies the hero may need to add to the group will be procured by this stage.

Taverns, inns, saloons, and other gathering places for adventurers are a great place for this stage. They are useful for the hero to gather information about the world and their mission, and both enemies and allies may be found at such places.

Approach to the Innermost Cave

The hero, nearing the center of the story and the special magical world, experiences full and final separation from her or his known world and idea of self. Entering this stage of the journey is analogous to undergoing change. This stage can and often does involve enemies, dangers, grief, or other such setbacks. It is also a stage of discovery and power.

The hero will now prepare and at last journey into the inner sanctum of the enemy, the unknown, or whatever form the antagonist has taken. Crossing this threshold and entering the lair is another key part of the monomyth. Many of these throughout human history used underground settings, such as the Labyrinth and the Abyss.

The Ordeal

The hero faces the greatest challenge yet. The hero often meets the villain in this stage if she or he hasn’t already. The hero has the proverbial “darkest hour,” where she or he will face death and come back from the brink. The audience (players) will be in the most suspense, not knowing if their heroes will live or die.

This critical moment in the hero’s journey should be an emotional rollercoaster. This moment requires the hero to die, literally or figuratively, so that she or he can come back again. This is a huge source of energy and punch for the monomyth, and one of the primary driving engines that makes it work and makes it resonate so profoundly with most if not all people.The experiences of the lead up stages have brought us (or should have brought us) to identify, empathize, and invest in the character. The GM and players are now made to experience the brink-of-death moment right along with the hero, and if the storyteller has done a good job, the experience will confer the utmost concern and anxiety to all interested parties. That’s why the investment is so crucial. This is where everything either comes together, or falls apart.

Reward

The hero has survived death, slain the BBEG, and “seized the elixir” (the reward). Players and GM now have cause to celebrate. This is the appropriate point in the monomyth and in any sensible fantasy adventure for the hero to take possession of the reward of the story, be it monetary, material, spiritual, knowledge, magic, or anything else. The hero has risked or sacrificed her or his life on behalf of the community in the ordinary world, and truly earned the title of “hero.”

ACT III

The Road Back

The hero may not be safe just yet. Sometimes, the BBEG is not killed in The Ordeal, and will be in hot pursuit during The Road Back. Some of the greatest chase scenes come in this phase.

The magical special world is being left behind, but the hero is now forever changed.

The Resurrection

The ancient warriors returned to the village with blood on their hands and had to purify themselves before returning to their people. Having faced and overcome the ordeal, the hero comes back, reborn (figuratively or literally in the case of Fantasy RPG’s), having been fully purified and ready to reenter the ordinary world (go home).

Return with the Elixir

The hero receives the final reward for defeating the "BBEG," and (again, in the archetypical mythical structure), returns with this gift to improve her or his ordinary world. The journey is meaningless without a reward to bring back. The reward can be experience or knowledge, too. But ultimately this elixir has the power to heal and restore balance to the universe.

The Hero’s Journey is an approximate framework that should guide but not railroad your adventure. Within this framework there should be room for surprises, unexpected decisions, and room for the story to grow organically from player choices. Feel free to experiment with moving or omitting some of these plot points to see how that affects the feel of the adventure.

My philosophy and feelings on roleplaying are that it is a story and a creative outlet as well as a game. An invulnerable (or more often, near or functionally invulnerable) character is not one that participants are as likely to attach to in a story, because most people cannot relate. A character that has weaknesses and uniqueness is more likely to garner an emotional response from the audience.

We are required to get emotionally attached to the characters to have a story. When a participant in a story says, “Gee, I hope my favorite character escapes this danger!”, and that character is up against something that appears more powerful, insurmountable, and so on, tension is created. This dramatic tension is the engine that drives every great hero story—no exceptions.

If that character is superpowered, or in some way seems unkillable, the tension falls like a house of cards. Without the tension, there is no story. Without the tension, there is no adventure or risk. Without any real risk, the rewards are mere participation trophies; the conclusion is foregone; the reward is inevitable. This is something I hope to avoid in many aspects throughout the game, as it is often a campaign killer, or requires some heavy-handed and cheap-feeling contrivance to reduce the players’ equipment or power in order to allow the story to continue.

Last edited: