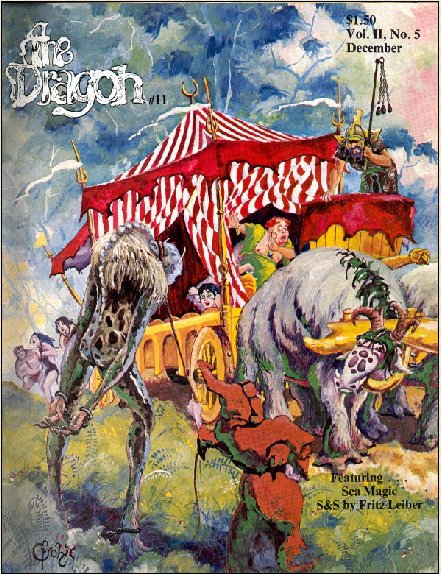

The Dragon Issue 11 was published in December 1977. It is 38 pages long, with a cover price of $1.50. This issue saw the introduction of an important new column.

Editor Tim Kask is once more talking about fiction, with a new Fritz Lieber story this issue and upcoming stories from Andre Norton and L. Sprague de Camp. Kask also proudly mentions that one of the Gardner Fox stories they published, "Shadow of a Demon," was included in Lin Carter's anthology "The Year's Best Fantasy Stories: 3". Kask loved publishing good fiction, though the readers were generally a little less enthusiastic.

He also mentions that last issue's board game, "Snit Smashing," was so well received that a sequel, "Snit's Revenge," was being included this month. These games really cemented Tom Wham's reputation as a designer.

Kask finishes his editorial with more good news for the fans--The Dragon is going to be published monthly! This was more evidence of the magazine's growth and popularity.

On to the issue itself, which contains plenty of interesting articles. There are two new combat sub-systems offered up. The quarter-staff rules by Jim Ward are a bit clunky and were never heard from again. Rob Kuntz's brawling rules are more elegant--certainly better than the grappling rules that eventually appeared in AD&D.

We also get another "Seal of the Imperium" column from M.A.R Barker. If I'm not mistaken, it is the last thing he ever published with TSR, although Dragon would continue to publish "Empire of the Petal Throne" articles for the next couple of years.

There is a short but profound article by Thomas Filmore called "The Play's The Thing..." It urges players to spend time developing the backstory and personality of their characters. He writes:

This seems like very basic and obvious stuff in 2018 but these ideas were still all being worked out back in 1977. I can't find much else by Thomas Filmore, but this little article is still quoted right down to the present day.

We also have another Gygax article, this one with the peculiar title of "View from the Telescope Wondering Which End is Which". In this piece, he defends TSRs right to protect its intellectual property and also denies they are behaving in an anti-competitive manner. He writes:

It's hard to disagree with anything he has written here, but TSR would soon develop a reputation for being overly litigious. And the great irony is that Gygax himself would become the favored target of TSR's lawyers in the not too distant future.

In my view, the most important article in the magazine is "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" by Robert J. Kuntz, who I find one of the most fascinating and enigmatic figures from the early history of the game.

As a teenager in Lake Geneva, Kuntz developed a passion for gaming and soon became Gary Gygax's precocious protege. He was there at the birth of D&D itself, being part of the original playtest group that ran from 1972 up until the first publication of the game in 1974. He went on to author important works such as the "Greyhawk" supplement and "Deities and Demigods". Kuntz was TSR's sixth fulltime employee, but he quit when it became clear that the job involved more administration than game design.

After leaving TSR, Kuntz continued to contribute to the hobby as a freelancer. His publishing record is impressive but spotty, and he has noted elsewhere that publication is not high on his list of priorities. His career has had a strangely nomadic quality about it. He shows up every now and again with original designs and opinions (sometimes brilliant, sometimes obtuse) and then disappears again, like a ghost from the dawn of the hobby. He is a genuinely interesting and original character.

"From the Sorcerer's Scroll" was intended as a regular column wherein he would publish new material (such as magic items and player options) as well as answer player questions. The first column, however, focused mostly on the business aspect of D&D, discussing things like the upcoming product schedule and how the game was faring overseas.

As it happened, Kuntz would only go on to author two more of these columns before Gygax took over (possibly because Kuntz left TSR). Gygax soon put his stamp on the column, using it to share new game material, and also to ruminate on game design philosophy and the state of the RPG industry. In my view, it is the most consistently interesting column in the early issues of Dragon and often provides fascinating insights into the development of the hobby. I do wish that Rob Kuntz had penned a few more of them, though!

In the next issue, great Cthulhu rises from the depths and clashes with D&D!

This article was contributed by M.T. Black as part of EN World's Columnist (ENWC) program.M.T. Black is a game designer and DMs Guild Adept. Please follow him on Twitter @mtblack2567 and sign up to his mailing list. We are always on the lookout for freelance columnists! If you have a pitch, please contact us!

Editor Tim Kask is once more talking about fiction, with a new Fritz Lieber story this issue and upcoming stories from Andre Norton and L. Sprague de Camp. Kask also proudly mentions that one of the Gardner Fox stories they published, "Shadow of a Demon," was included in Lin Carter's anthology "The Year's Best Fantasy Stories: 3". Kask loved publishing good fiction, though the readers were generally a little less enthusiastic.

He also mentions that last issue's board game, "Snit Smashing," was so well received that a sequel, "Snit's Revenge," was being included this month. These games really cemented Tom Wham's reputation as a designer.

Kask finishes his editorial with more good news for the fans--The Dragon is going to be published monthly! This was more evidence of the magazine's growth and popularity.

On to the issue itself, which contains plenty of interesting articles. There are two new combat sub-systems offered up. The quarter-staff rules by Jim Ward are a bit clunky and were never heard from again. Rob Kuntz's brawling rules are more elegant--certainly better than the grappling rules that eventually appeared in AD&D.

We also get another "Seal of the Imperium" column from M.A.R Barker. If I'm not mistaken, it is the last thing he ever published with TSR, although Dragon would continue to publish "Empire of the Petal Throne" articles for the next couple of years.

There is a short but profound article by Thomas Filmore called "The Play's The Thing..." It urges players to spend time developing the backstory and personality of their characters. He writes:

"When you roll up your next character, try investing more in him than just the six die rolls. Try to create a colorful background for him. Give him a purpose and reason for being where and what he is. Could it be that he is a rich bastard, always getting his way due to position and wealth and expects to do so now? Or was he a serf that rose up and killed one of his Lord’s men and is now an adventurer/outlaw? How would your character react to authority, what does he want in life? Does he have a drinking problem? Does he chase women? Is he brave? Greedy? Tricky? Just what does he want from adventuring? By investing a few minutes into developing your character, you can extend the game down hundreds of new avenues."

This seems like very basic and obvious stuff in 2018 but these ideas were still all being worked out back in 1977. I can't find much else by Thomas Filmore, but this little article is still quoted right down to the present day.

We also have another Gygax article, this one with the peculiar title of "View from the Telescope Wondering Which End is Which". In this piece, he defends TSRs right to protect its intellectual property and also denies they are behaving in an anti-competitive manner. He writes:

"So to restate our position, TSR does not object to honest competition. We will not praise our imitators, but neither will we try to drive them out of business. Frankly, we are too busy running our own affairs to worry overmuch about competitors. TSR co-operates with certain firms in order to produce D&D associated products, offerings which add to the game. For this co-operation and for the right to display the D&D logo, we receive a small royalty to compensate us for our past and present expenditures in time and money. Under no circumstances will we permit individuals or companies to make unauthorised use of our materials."

It's hard to disagree with anything he has written here, but TSR would soon develop a reputation for being overly litigious. And the great irony is that Gygax himself would become the favored target of TSR's lawyers in the not too distant future.

In my view, the most important article in the magazine is "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" by Robert J. Kuntz, who I find one of the most fascinating and enigmatic figures from the early history of the game.

As a teenager in Lake Geneva, Kuntz developed a passion for gaming and soon became Gary Gygax's precocious protege. He was there at the birth of D&D itself, being part of the original playtest group that ran from 1972 up until the first publication of the game in 1974. He went on to author important works such as the "Greyhawk" supplement and "Deities and Demigods". Kuntz was TSR's sixth fulltime employee, but he quit when it became clear that the job involved more administration than game design.

After leaving TSR, Kuntz continued to contribute to the hobby as a freelancer. His publishing record is impressive but spotty, and he has noted elsewhere that publication is not high on his list of priorities. His career has had a strangely nomadic quality about it. He shows up every now and again with original designs and opinions (sometimes brilliant, sometimes obtuse) and then disappears again, like a ghost from the dawn of the hobby. He is a genuinely interesting and original character.

"From the Sorcerer's Scroll" was intended as a regular column wherein he would publish new material (such as magic items and player options) as well as answer player questions. The first column, however, focused mostly on the business aspect of D&D, discussing things like the upcoming product schedule and how the game was faring overseas.

As it happened, Kuntz would only go on to author two more of these columns before Gygax took over (possibly because Kuntz left TSR). Gygax soon put his stamp on the column, using it to share new game material, and also to ruminate on game design philosophy and the state of the RPG industry. In my view, it is the most consistently interesting column in the early issues of Dragon and often provides fascinating insights into the development of the hobby. I do wish that Rob Kuntz had penned a few more of them, though!

In the next issue, great Cthulhu rises from the depths and clashes with D&D!

This article was contributed by M.T. Black as part of EN World's Columnist (ENWC) program.M.T. Black is a game designer and DMs Guild Adept. Please follow him on Twitter @mtblack2567 and sign up to his mailing list. We are always on the lookout for freelance columnists! If you have a pitch, please contact us!