G

Guest 7015810

Guest

1 Introduction

Gary Gygax stated that Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) started with Gygax and Perren’s Chainmail, which Dave

Arneson then used to create his Blackmoor campaign:

"From the Chainmail fantasy rules [Arneson] drew ideas for a far more complex and exciting game, and

thus began a campaign which still thrives as of this writing!" (Dungeons & Dragons, 1974) [1]

"In case you don't know the history of D&D, it all began with the fantasy rules in Chainmail. Dave A.

took those rules and changed them into a prototype of what is now D&D." (Alarums & Excursions, 1975) [2]

“The D&D game was drawn from [Chainmail’s] rules, and that is indisputable. Chainmail was the

progenitor of D&D, but the child grew to excel its parent.” (Heroic Worlds, 1991) [3]

In his widely read The Dragon article, “Gary Gygax on Dungeons & Dragons: Origins of the Game,” Gygax

characterized Arneson’s campaign as an “amended Chainmail fantasy campaign.” [4] However, in the same article, Gygax seemed to indicate that Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign was already underway when Chainmail was first published:

[Arneson] began a local medieval campaign for the Twin Cities gamers […] The medieval rules,

CHAINMAIL (Gygax and Perren) were published in Domesday Book prior to publication by Guidon

Games. […] Between the time they appeared in Domesday Book and their publication by Guidon

Games, I revised and expanded the rules for 1:20 and added 1:1 scale games, jousting, and fantasy. […]

When the whole appeared as CHAINMAIL, Dave began using the fantasy rules for his campaign […] [5]

As Gygax had noted, predecessors of the mass-combat, man-to-man, and jousting rules of Chainmail had been previously published in Gygax’s and Rob Kuntz’s medieval newsletter Domesday Book in 1970. However, the Fantasy Supplement was not; it was first published as part of the Chainmail booklet.

This article contains several sections. In section 2, some background is given on three rulesets. In section 3, an analysis using the rulesets will be presented that suggests that Dave Arneson, the little-known coauthor of D&D, contributed material to the Fantasy Supplement from his Blackmoor campaign. In the section 4, this result will be cross-checked . In section 5, what Arneson may have sent to Gygax is detailed.

2 Background

Some background is needed on three sets of rules:

“Rules for Middle Earth”

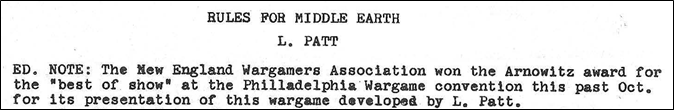

These rules were written by Leonard Patt and based on Lord of the Rings. They were demonstrated by the New England Wargamers Association (NEWA) at the Miniature Figure Collectors of America convention on October 10th, 1970. [6] The rules include dragons, dwarves, elves, ents, hobbits, orcs, and trolls. Additionally, rules are included for playing heroes, anti-heroes (evil heroes), and wizards. The rules even include the “Fire ball” spell. “Rules for Middle Earth” was first published in The Courier around November of 1970 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The beginning of Rules for Middle Earth by Leonard Patt, which was first published in NEWA's The Courier around November of 1970.

Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement

The 16-page Fantasy Supplement at the back of Chainmail is a set of skirmish wargaming rules (where one figure represents one creature) when used by itself, although it also includes stats for having Fantasy creatures battle armies using the mass-combat rules of Chainmail. The Fantasy Supplement includes all the creatures from Patt’s Rules for Middle Earth and shares textual similarities (in some cases verbatim) with Patt’s rules as well. [7] The Fantasy Supplement consists of three parts: a set of creature descriptions, the Fantasy Reference Table (a table listing stats for the creatures), and the Fantasy Combat Table (a table for resolving combat between two creatures). Gygax claimed authorship of the Fantasy Supplement and Jeff Perren is not known to have disputed that claim. [8][9][10] The Fantasy Supplement was first published around May of 1971 as part of the Chainmail booklet (see Figure 2).

The First Fantasy Campaign

The First Fantasy Campaign by Dave Arneson was first published in 1977, but contains material from Arneson’s original Blackmoor campaign dating back to the early 70’s. Arneson said “First Fantasy Campaign, which I did for Judges Guild, is literally my original campaign notes without any plots or real organization.” [11] The booklet (see Figure 2) appears to contain a mix of material from different points in time throughout Arneson’s campaign.

Figure 2: the first printings of Chainmail and The First Fantasy Campaign

3 The Analysis

3.1 Overview

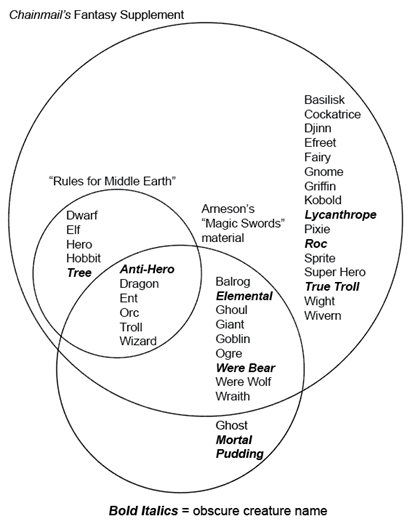

This analysis focuses on comparing lists of creature names that Arneson used during the Blackmoor campaign with the creature names contained in both Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement. Each list of creature names forms a set; by comparing these sets, relationships between them will be determined. It is important to note that absolute dates do not play a role in this type of analysis; only the relative order in which the lists of creature name were created is relevant. The basis for this analysis is the Venn diagram shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: A Venn diagram of creature names appearing in Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, "Rules for Middle Earth," and Arneson's "Magic Swords" material

This analysis begins with the definition of the term “obscure creature name.” An obscure creature name is a word or phrase that is highly unusual in the context of being the name of a creature. For example, “tree” is not an obscure word, but in the context of being a creature name, it qualifies as being an obscure creature name.

3.2 The Relationships Between the Rulesets Based on Figure 3

Patt and Arneson

Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appear to be related, as they both share the obscure creature name “Anti-Hero.” Arneson lived in Minnesota at the time, while Patt lived in New England. Since Arneson did not publish any mention of Blackmoor prior to April of 1971, [12] and then only to his local group in his own newsletter, while Patt published in The Courier around November of 1970, the odds of Arneson not drawing material from Patt’s rules appears to be negligible (The Courier was a well-known early wargaming magazine that was distributed both to subscribers and to hobby stores). Note that Arneson could have drawn from Patt’s material by drawing from Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement, since that text includes the “Anti-Hero” as well; Whether Arneson’s material and Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement came first will be determined in section 3.3.

Patt and Gygax

Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Gygax’s “Fantasy Supplement” are also clearly related, as they share two obscure creature names, “Anti-Hero” and “Tree.” Since the Fantasy Supplement was published around May 15, 1971 and Patt’s rules was published around November of 1970, the chance that both sets of rules share both the Anti-Hero and the Tree by coincidence is negligible. Since Patt’s rules predate the Fantasy Supplement by approximately six months, Gygax appears to have drawn from Patt’s rules.

Arneson and Gygax

Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material and Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement are also clearly related, as they share three obscure creature names, “Anti-Hero,” “Elemental,” and “Were Bear.” However, since the “Magic Swords” material is undated, it isn’t immediately clear which came first.

3.3 Determining Which Came First, Arneson’s Material or Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement

Another section of The First Fantasy Campaign provides additional information that can help determine whether Arneson’s material or Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement came first. In the “Magic Protection Points” section on page 44, Arneson states:

"Having gone over all my records the surest indication is that the point values given in 1st Edition Chainmail formed the basis for my system. Exceptions occurred were due to the addition of new Creatures beyond those given in Chainmail and thus necessitating changes. Here is what I then came up with.

GROUP I CREATURES- Balrog, Dragon, Elemental, Ent, Giant, True Troll, Wraith

GROUP II- Lycanthrope, Hero, SuperHero, Roc, Troll, Ogre, Ghoul

GROUP III- Orcs, Elves, Dwarves, Gnomes, Kobolds, Goblins, Elves, Fairies, Sprites, Pixies, Hobbits"

Arneson wrote that he developed this creature list after Chainmail was published. Notably, the “Magic Protection Points” material above includes different creatures than Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material. Since the “Magic Protection Points” material includes all three obscure creature names from Chainmail (Lycanthrope, Roc, True Troll), the “Magic Protection Points” material does indeed appear to have come after Chainmail. Taking into account that the “Magic Protection Points” material must follow the publication of Chainmail, the three sets of creature names could have been produced in only three different orders, as shown as three cases below:

Case A

1) Chainmail 2) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material 3) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material

Case B

1) Chainmail 2) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material 3) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material

Case C

1) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material 2) Chainmail 3) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material

Case A is shown in Table 1, Case B is shown in Table 2, and Case C is shown in Table 7. Creatures that are unique to Chainmail are boldfaced in the "Magic Protection Points" columns.

Case A (Chainmail, “Magic Swords,” “Magic Protection Points,” as shown in Table 1)

This would mean that, starting with the creatures in Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, Arneson then:

Table 1: Assumed Order: 1) Chainmail 2) “Magic Swords” 3) “Magic Protection Points”

Case B (Chainmail, “Magic Protection Points,” “Magic Swords,” as shown in Table 2)

This would mean that, starting with Chainmail, Arneson then:

Table 2: Assumed Order: 1) Chainmail 2) “Magic Protection Points” 3) “Magic Swords”

Case C (“Magic Swords,” Chainmail, “Magic Protection Points,” as shown in Table 3)

This would mean that, starting from the “Magic Swords” material, Gygax:

Table 3: Assumed Order: 1) “Magic Swords” 2) Chainmail 3) “Magic Protection Points”

4 Cross-Checking the Analysis

4.1 Case C is Consistent with the First Dungeon Adventure Occurring Around Christmas of 1970

Dave Arneson stated in The First Fantasy Campaign (1977):

The Dungeon was first established in the Winter and Spring of 1970-71 and it grew from there. [13]

Original Blackmoor player Greg Svenson has published his recollections of the first dungeon adventure in The First Dungeon Adventure. [14] He wrote:

I have the unique experience of being the sole survivor of the first dungeon adventure in the history of “Dungeons & Dragons,” indeed in the history of role-playing in general. This is the story of that first dungeon adventure.

During the Christmas break of 1970-71, our gaming group was meeting in Dave Arneson's basement in St. Paul, Minnesota. […] [15]

When asked about his dating, Svenson said that another player had “confirmed the timing when I talked to him at Dave Arneson's funeral in 2009.” [16] During the first dungeon adventure, the party found a magic sword:

We found a magic sword on the ground. […] one of the players tried to pick it up. He received a shock and was thrown across the room. The same thing happened to the second player to try. When Bill tried to pick it up he was successful. We were all impressed and Dave declared Bill our leader and elevated him to “hero” status. [17]

Since the players found a magic sword during the first dungeon adventure, the “Magic Swords” material almost certainly must have existed by Svenson’s Christmas break of 1970-71. Since Chainmail was not published until approximately May of 1971,[18] and Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material includes material from Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, the order given by Arneson and Svenson (which was confirmed by a third player) would be 1) the “Magic Swords” material, 2) Chainmail, and 3) the “Magic Protection Points” material—the same order given by Case C in section 3.

4.2 Case C is Consistent with Arneson’s Dating of the “Magic Swords” Material

Arneson said in an introduction to the Magic Swords section (p. 64) of The First Fantasy Campaign:

Prior to setting up Blackmoor I spent a considerable effort in setting up an entire family of Magical swords. The swords, indeed comprise most of the early magical artifacts. [19]

If the “Magic Swords” material predated Blackmoor, it would predate the “Magic Protection Points” material; this is consistent with Case C.

4.3 Case C is Consistent with “Lycanthrope” Frequently Appearing in The First Fantasy Campaign

“Lycanthrope” appears 25 times in The First Fantasy Campaign, while “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” only appear once (in the “Magic Swords” material). This suggests that “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” were only used for a short period of time, while “Lycanthrope” was used for a much longer period of time. As shown in Case 3’s Table 3, “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” would have been Arneson’s early creature names, which Arneson soon replaced with Gygax’s “Lycanthrope” grouping term for Werebears and Werewolves after he began using Chainmail. Therefore, Arneson would have used “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” for less than a year (no longer than from when he first encountered Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” to when he started using Chainmail), while he would have used the term “Lycanthrope” for years. Arneson noted on page 87 of The First Fantasy Campaign that the Bleakwood section “was for special convention demonstrations but was only used at Gencon VIII”; Gen Con VIII took place in August of 1975, demonstrating that The First Fantasy Campaign includes material from years of play (during most of which Arneson appears to have used the term “Lycanthrope,” thus accounting for its great frequency in The First Fantasy Campaign compared to “Were Bears” and “Were Wolves”)

5 What Arneson May Have Sent to Gygax

Based on the above analysis, Arneson appears to have sent Gygax material that included all the creature names from the “Magic Swords” material appearing in The First Fantasy Campaign. Note that this does not necessarily mean that Arneson actually sent Gygax the “Magic Swords” material; the creature names and powers from the “Magic Swords” material could have also been included in a list of creature descriptions or in table similar to the Fantasy Reference Table instead. However, since Gygax did include magic swords in Chainmail, whereas Patt had not included them in “Rules for Middle Earth,” Arneson almost certainly included some material at least referencing magic swords with the material that he sent to Gygax.

Arneson having a list of creature names in the “Magic Swords” material implies that he also had some game-related information to go along with those creature names, such as stats and/or descriptions. Assuming that this is the case, Gygax likely incorporated much of that material into Chainmail after editing it (this is what Gygax appears to have done with material he incorporated into Chainmail from both Domesday Book and from Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth”). Therefore, Arneson’s material in Chainmail is likely to be largely intact, and this appears to be supported by the creature names from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appearing in Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement largely verbatim. Arneson also provided a list of abilities in the “Magic Swords” material:

Cause Morale Check

Combat Increase

Evil Detection

Intelligence Increase

Invisibility

Invisibility Detection

Magic Ability

Magic Detection

Paralize

Raise Morale

See in Darkness

Strength

Just as in the case of creature names, these appear verbatim or nearly verbatim in both the creature descriptions and in the Fantasy Reference Table. For example, the Wraith creature description reads:

"WRAITHS (Nazgul etc.): Wraiths can see in darkness, raise the morale of friendly troops as if they were Heroes, cause the enemy to check morale as if they were Super Heroes, and paralize any enemy man […]"

The Fantasy Supplement is comprised of three parts: 1) creature descriptions, 2) the Fantasy Reference Table, and 3) the Fantasy Combat Table. It appears likely that Arneson sent Gygax earlier versions of all three of them.

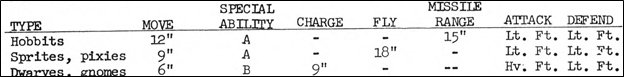

5.1 Creature Descriptions

Arneson included a set of creature descriptions at the back of The First Fantasy Campaign that are similar to those in Chainmail. They appear to date sometime between when he started using Chainmail and when D&D was published (since they include material from Chainmail but not D&D). This alone doesn’t indicate that Arneson probably sent Gygax creature descriptions, but there is another piece of evidence indicating that he probably did: the “Giant” entry is missing from the creature descriptions of Chainmail, but included on both the Fantasy Reference Table and the Fantasy Combat Table. Since the ATTACK and DEFEND stats for using the Giant with the mass-combat rules of Chainmail were listed as “Special” (see Figure 4), Gygax would have needed to have specified them in the creature description for the Giant (just like the other creatures listed as “Special”). However, Arneson had no such need, and likely would not have bothered with writing a creature description for the Giant (which was simply a large human). Supporting this is the fact that the Giant is the only creature listed on the Fantasy Reference Table with no special ability. Therefore, what appears likely to have happened is that Gygax prepared his creature descriptions from a set of creature descriptions that Arneson had provided and simply didn’t notice that Arneson had not provided a creature description for the Giant. If Gygax had written his creature descriptions based on the earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table that Arneson appears to have sent him (see below), he likely wouldn’t have omitted the Giant, since it appears to have been listed there. Therefore, it appears that Arneson gave Gygax creature descriptions. Arneson’s creature descriptions almost certainly would have included ability names that he had also listed in his “Magic Swords” material (e.g., see the Wraith description above). Gygax likely then expanded them into the creature descriptions seen in the Fantasy Supplement.

Figure 4: A portion from the Fantasy Reference Table

5.2 Fantasy Reference Table

The Fantasy Reference Table (see Figure 5) bears a resemblance to the “Figure Characteristics” table from Arneson’s and Hoffa’s 1969 ruleset Strategos A (see Table 4); a reformatted version of the Strategos A table is shown as Table 5 (compare Table 5 to Figure 5). Arneson’s original reference table that he appears to have sent to Gygax likely didn’t include the last two columns of ATTACK and DEFEND stats for using the fantasy creatures with the mass-combat rules of Chainmail; Gygax appears to have added those. When Table 4 from Strategos A is reformatted slightly, it more closely resembles the Fantasy Reference Table (compare Figure 5 and Table 5 below).

Additional evidence that Arneson sent Gygax an earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table is shown in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, the first six abilities on the Fantasy Reference Table appear to have a corresponding ability in the list of abilities included in the “Magic Swords” material of The First Fantasy Campaign. Since Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appears to predate the Fantasy Supplement per the analysis in section 3, Gygax appears to have drawn the first six abilities on the Fantasy Reference Table from material from Arneson. Given the resemblance of the Fantasy Reference Table to Arneson’s and Hoffa’s Strategos A table, it appears likely that Arneson provided an earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table that Gygax then drew from.

Table 4: The top of the "Figure Characteristics" table from Arneson's and Hoffa’s Strategos A (1969)

Figure 5: The top of the Fantasy Reference Table from Chainmail

Table 5: A Version of Table 4 Reformatted to Look Like the Fantasy Reference Table in Figure 5

Table 6: Abilities from Arneson's "Magic Swords" material vs. the Abilities Listed in the Fantasy Reference Table

5.3 Fantasy Combat Table

Arneson said:

So we quickly came up with twenty or thirty [monsters]. We tried setting them up in a matrix, but that didn’t work because it was quickly taking up an entire wall. [20]

Although Arneson was likely speaking figuratively regarding “taking up an entire wall,” the problem he appears to have had was that if he included n creatures in his matrix, he’d need to fill out n2 entries in the table. For example, if he had 5 monsters, he’d need to fill out 25 entries; with 10 monsters, 100 entries; with 20 monsters, 400 entries; with 30 monsters, 900 entries. He explained the problem plainly: “The combat matrix became a thing of the past. There were over 30 critters, and the 30x30 matrix became unwieldy.” [21] Arneson’s description of his “combat matrix” clearly matches the format of the Fantasy Combat Table from Chainmail, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: The Fantasy Combat Table from Chainmail

Most of the creatures on the Fantasy Combat Table were likely on Arneson’s original “combat matrix.” The creatures shown on the Fantasy Combat Table that are unique to Chainmail (Lycanthrope, Roc, and Wight), couldn’t have been on Arneson’s original table. Since Arneson didn’t include “Tree” in either the “Magic Swords” or “Magic Protection Points” tables, he likely didn’t include it in the “combat matrix” either.

Gygax included ATTACK and DEFEND stats (see Figure 5) on the Fantasy Reference Table for resolving battles between men and fantasy creatures such as dragons using Chainmail’s mass-combat rules; this appears to be the reason there is no Man entry in the Fantasy Combat Table, nor the humanoids Goblin and Orc. Arneson probably used the term Mortal for Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Hobbits (since Patt’s rules included these races, but no Mortal, while Arneson’s rules included Mortal, but none of the others). Therefore, Arneson’s Fantasy Combat Table likely had a Mortal entry.

Gygax added every creature from Patt’s rules and all but the Ghost, Mortal, and Pudding from Arneson’s. The Mortal, per above, was likely a grouping term for Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Hobbits, and since Gygax effectively included all four (Men being in the other sections of Chainmail), he wouldn’t have needed the Mortal. Gygax may have eliminated Pudding for a variety of reasons (e.g., it wasn’t a creature typically associated with the Fantasy genre). It is more difficult to explain why he didn’t include the Ghost, as he had included the Ghoul. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that Gygax simply changed the name of the Ghost to Wight.

6 References

Gary Gygax stated that Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) started with Gygax and Perren’s Chainmail, which Dave

Arneson then used to create his Blackmoor campaign:

"From the Chainmail fantasy rules [Arneson] drew ideas for a far more complex and exciting game, and

thus began a campaign which still thrives as of this writing!" (Dungeons & Dragons, 1974) [1]

"In case you don't know the history of D&D, it all began with the fantasy rules in Chainmail. Dave A.

took those rules and changed them into a prototype of what is now D&D." (Alarums & Excursions, 1975) [2]

“The D&D game was drawn from [Chainmail’s] rules, and that is indisputable. Chainmail was the

progenitor of D&D, but the child grew to excel its parent.” (Heroic Worlds, 1991) [3]

In his widely read The Dragon article, “Gary Gygax on Dungeons & Dragons: Origins of the Game,” Gygax

characterized Arneson’s campaign as an “amended Chainmail fantasy campaign.” [4] However, in the same article, Gygax seemed to indicate that Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign was already underway when Chainmail was first published:

[Arneson] began a local medieval campaign for the Twin Cities gamers […] The medieval rules,

CHAINMAIL (Gygax and Perren) were published in Domesday Book prior to publication by Guidon

Games. […] Between the time they appeared in Domesday Book and their publication by Guidon

Games, I revised and expanded the rules for 1:20 and added 1:1 scale games, jousting, and fantasy. […]

When the whole appeared as CHAINMAIL, Dave began using the fantasy rules for his campaign […] [5]

As Gygax had noted, predecessors of the mass-combat, man-to-man, and jousting rules of Chainmail had been previously published in Gygax’s and Rob Kuntz’s medieval newsletter Domesday Book in 1970. However, the Fantasy Supplement was not; it was first published as part of the Chainmail booklet.

This article contains several sections. In section 2, some background is given on three rulesets. In section 3, an analysis using the rulesets will be presented that suggests that Dave Arneson, the little-known coauthor of D&D, contributed material to the Fantasy Supplement from his Blackmoor campaign. In the section 4, this result will be cross-checked . In section 5, what Arneson may have sent to Gygax is detailed.

2 Background

Some background is needed on three sets of rules:

“Rules for Middle Earth”

These rules were written by Leonard Patt and based on Lord of the Rings. They were demonstrated by the New England Wargamers Association (NEWA) at the Miniature Figure Collectors of America convention on October 10th, 1970. [6] The rules include dragons, dwarves, elves, ents, hobbits, orcs, and trolls. Additionally, rules are included for playing heroes, anti-heroes (evil heroes), and wizards. The rules even include the “Fire ball” spell. “Rules for Middle Earth” was first published in The Courier around November of 1970 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The beginning of Rules for Middle Earth by Leonard Patt, which was first published in NEWA's The Courier around November of 1970.

Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement

The 16-page Fantasy Supplement at the back of Chainmail is a set of skirmish wargaming rules (where one figure represents one creature) when used by itself, although it also includes stats for having Fantasy creatures battle armies using the mass-combat rules of Chainmail. The Fantasy Supplement includes all the creatures from Patt’s Rules for Middle Earth and shares textual similarities (in some cases verbatim) with Patt’s rules as well. [7] The Fantasy Supplement consists of three parts: a set of creature descriptions, the Fantasy Reference Table (a table listing stats for the creatures), and the Fantasy Combat Table (a table for resolving combat between two creatures). Gygax claimed authorship of the Fantasy Supplement and Jeff Perren is not known to have disputed that claim. [8][9][10] The Fantasy Supplement was first published around May of 1971 as part of the Chainmail booklet (see Figure 2).

The First Fantasy Campaign

The First Fantasy Campaign by Dave Arneson was first published in 1977, but contains material from Arneson’s original Blackmoor campaign dating back to the early 70’s. Arneson said “First Fantasy Campaign, which I did for Judges Guild, is literally my original campaign notes without any plots or real organization.” [11] The booklet (see Figure 2) appears to contain a mix of material from different points in time throughout Arneson’s campaign.

Figure 2: the first printings of Chainmail and The First Fantasy Campaign

3 The Analysis

3.1 Overview

This analysis focuses on comparing lists of creature names that Arneson used during the Blackmoor campaign with the creature names contained in both Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement. Each list of creature names forms a set; by comparing these sets, relationships between them will be determined. It is important to note that absolute dates do not play a role in this type of analysis; only the relative order in which the lists of creature name were created is relevant. The basis for this analysis is the Venn diagram shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: A Venn diagram of creature names appearing in Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, "Rules for Middle Earth," and Arneson's "Magic Swords" material

This analysis begins with the definition of the term “obscure creature name.” An obscure creature name is a word or phrase that is highly unusual in the context of being the name of a creature. For example, “tree” is not an obscure word, but in the context of being a creature name, it qualifies as being an obscure creature name.

3.2 The Relationships Between the Rulesets Based on Figure 3

Patt and Arneson

Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appear to be related, as they both share the obscure creature name “Anti-Hero.” Arneson lived in Minnesota at the time, while Patt lived in New England. Since Arneson did not publish any mention of Blackmoor prior to April of 1971, [12] and then only to his local group in his own newsletter, while Patt published in The Courier around November of 1970, the odds of Arneson not drawing material from Patt’s rules appears to be negligible (The Courier was a well-known early wargaming magazine that was distributed both to subscribers and to hobby stores). Note that Arneson could have drawn from Patt’s material by drawing from Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement, since that text includes the “Anti-Hero” as well; Whether Arneson’s material and Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement came first will be determined in section 3.3.

Patt and Gygax

Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” and Gygax’s “Fantasy Supplement” are also clearly related, as they share two obscure creature names, “Anti-Hero” and “Tree.” Since the Fantasy Supplement was published around May 15, 1971 and Patt’s rules was published around November of 1970, the chance that both sets of rules share both the Anti-Hero and the Tree by coincidence is negligible. Since Patt’s rules predate the Fantasy Supplement by approximately six months, Gygax appears to have drawn from Patt’s rules.

Arneson and Gygax

Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material and Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement are also clearly related, as they share three obscure creature names, “Anti-Hero,” “Elemental,” and “Were Bear.” However, since the “Magic Swords” material is undated, it isn’t immediately clear which came first.

3.3 Determining Which Came First, Arneson’s Material or Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement

Another section of The First Fantasy Campaign provides additional information that can help determine whether Arneson’s material or Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement came first. In the “Magic Protection Points” section on page 44, Arneson states:

"Having gone over all my records the surest indication is that the point values given in 1st Edition Chainmail formed the basis for my system. Exceptions occurred were due to the addition of new Creatures beyond those given in Chainmail and thus necessitating changes. Here is what I then came up with.

GROUP I CREATURES- Balrog, Dragon, Elemental, Ent, Giant, True Troll, Wraith

GROUP II- Lycanthrope, Hero, SuperHero, Roc, Troll, Ogre, Ghoul

GROUP III- Orcs, Elves, Dwarves, Gnomes, Kobolds, Goblins, Elves, Fairies, Sprites, Pixies, Hobbits"

Arneson wrote that he developed this creature list after Chainmail was published. Notably, the “Magic Protection Points” material above includes different creatures than Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material. Since the “Magic Protection Points” material includes all three obscure creature names from Chainmail (Lycanthrope, Roc, True Troll), the “Magic Protection Points” material does indeed appear to have come after Chainmail. Taking into account that the “Magic Protection Points” material must follow the publication of Chainmail, the three sets of creature names could have been produced in only three different orders, as shown as three cases below:

Case A

1) Chainmail 2) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material 3) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material

Case B

1) Chainmail 2) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material 3) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material

Case C

1) Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material 2) Chainmail 3) Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material

Case A is shown in Table 1, Case B is shown in Table 2, and Case C is shown in Table 7. Creatures that are unique to Chainmail are boldfaced in the "Magic Protection Points" columns.

Case A (Chainmail, “Magic Swords,” “Magic Protection Points,” as shown in Table 1)

This would mean that, starting with the creatures in Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, Arneson then:

- added the Werebear and Werewolf sub-entries from Chainmail, but not the main Lycanthrope entry from Chainmail

- changed the spelling of the Werebear and Werewolf entries to the non-standard spellings “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf”

- added the Ghost, Mortal, and Pudding, all three of which were not in Chainmail

- didn’t add any creatures that are unique to Chainmail

- adding multiple creatures unique to Chainmail

- deleting the Ghost, the Mortal, and the Pudding

Table 1: Assumed Order: 1) Chainmail 2) “Magic Swords” 3) “Magic Protection Points”

| Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement | Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” Material | Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” Material |

| Anti-Hero | Anti-Hero | |

| Balrog | Balrog | Balrog |

| Dragon | Dragon | Dragon |

| Dwarf | Dwarf | |

| Gnome | Gnome | |

| Elemental | Elemental | Elemental |

| Elf | Elf | |

| Fairy | Fairy | |

| Ent | Ent | Ent |

| Tree | ||

| Ghost | ||

| Ghoul | Ghoul | Ghoul |

| Giant | Giant | Giant |

| Goblin | Goblin | Goblin |

| Kobold | Kobold | |

| Hero | Hero | |

| Hobbit | Hobbit | |

| Lycanthrope | Lycanthrope | |

| Werebear | Were Bear | |

| Werewolf | Were Wolf | |

| Mortal | ||

| Ogre | Ogre | Ogre |

| Orc | Orc | Orc |

| Pudding | ||

| Roc | Roc | |

| Sprite | Sprite | |

| Pixie | Pixie | |

| Super Hero | Super Hero | |

| Troll | Troll | Troll |

| True Troll | True Troll | |

| Wraith | Wraith | Wraith |

| Wizard | Evil Wizard |

This would mean that, starting with Chainmail, Arneson then:

- added multiple creatures unique to Chainmail

- didn’t include the Werebear and Werewolf sub-entries from the Lycanthrope entry from Chainmail

- deleting all the creatures unique to Chainmail

- adding back the Werebear and Werewolf, but changing them to the non-standard spellings Were Bear and Were Wolf

- adding the Ghost, Mortal and Pudding

Table 2: Assumed Order: 1) Chainmail 2) “Magic Protection Points” 3) “Magic Swords”

| Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement | Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” Material | Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” Material |

| Anti-Hero | Anti-Hero | |

| Balrog | Balrog | Balrog |

| Dragon | Dragon | Dragon |

| Dwarf | Dwarf | |

| Gnome | Gnome | |

| Elemental | Elemental | Elemental |

| Elf | Elf | |

| Fairy | Fairy | |

| Ent | Ent | Ent |

| Tree | ||

| Ghost | ||

| Ghoul | Ghoul | Ghoul |

| Giant | Giant | Giant |

| Goblin | Goblin | Goblin |

| Kobold | Kobold | |

| Hero | Hero | |

| Hobbit | Hobbit | |

| Lycanthrope | Lycanthrope | |

| Werebear | Were Bear | |

| Werewolf | Were Wolf | |

| Mortal | ||

| Ogre | Ogre | Ogre |

| Orc | Orc | Orc |

| Pudding | ||

| Roc | Roc | |

| Sprite | Sprite | |

| Pixie | Pixie | |

| Super Hero | Super Hero | |

| Troll | Troll | Troll |

| True Troll | True Troll | |

| Wraith | Wraith | Wraith |

| Wizard | Evil Wizard |

This would mean that, starting from the “Magic Swords” material, Gygax:

- added the Elemental, Ghoul, Giant, Goblin, Were Bear, Were Wolf, Ogre, and Wraith from material Arneson had provided to Gygax

- corrected Arneson’s non-standard spellings of “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” to Werebear and Werewolf

- added the grouping term “Lycanthrope” for the Werebear and the Werewolf

- dropped the Ghost, Mortal, and Pudding creatures that Arneson had created

- replacing the Werebear and the Werewolf with Gygax’s grouping term, Lycanthrope

- stopping use of the Ghost, Mortal, and Pudding

- starting to use creatures unique to Chainmail

Table 3: Assumed Order: 1) “Magic Swords” 2) Chainmail 3) “Magic Protection Points”

| Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” Material | Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement | Creatures from Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” Material |

| Anti-Hero | Anti-Hero | |

| Balrog | Balrog | Balrog |

| Dragon | Dragon | Dragon |

| Dwarf | Dwarf | |

| Gnome | Gnome | |

| Elemental | Elemental | Elemental |

| Elf | Elf | |

| Fairy | Fairy | |

| Ent | Ent | Ent |

| Tree | ||

| Ghost | ||

| Ghoul | Ghoul | Ghoul |

| Giant | Giant | Giant |

| Goblin | Goblin | Goblin |

| Kobold | Kobold | |

| Hero | Hero | |

| Hobbit | Hobbit | |

| Lycanthrope | Lycanthrope | |

| Were Bear | Werebear | |

| Were Wolf | Werewolf | |

| Mortal | ||

| Ogre | Ogre | Ogre |

| Orc | Orc | Orc |

| Pudding | ||

| Roc | Roc | |

| Sprite | Sprite | |

| Pixie | Pixie | |

| Super Hero | Super Hero | |

| Troll | Troll | Troll |

| True Troll | True Troll | |

| Wraith | Wraith | Wraith |

| Evil Wizard | Wizard |

4.1 Case C is Consistent with the First Dungeon Adventure Occurring Around Christmas of 1970

Dave Arneson stated in The First Fantasy Campaign (1977):

The Dungeon was first established in the Winter and Spring of 1970-71 and it grew from there. [13]

Original Blackmoor player Greg Svenson has published his recollections of the first dungeon adventure in The First Dungeon Adventure. [14] He wrote:

I have the unique experience of being the sole survivor of the first dungeon adventure in the history of “Dungeons & Dragons,” indeed in the history of role-playing in general. This is the story of that first dungeon adventure.

During the Christmas break of 1970-71, our gaming group was meeting in Dave Arneson's basement in St. Paul, Minnesota. […] [15]

When asked about his dating, Svenson said that another player had “confirmed the timing when I talked to him at Dave Arneson's funeral in 2009.” [16] During the first dungeon adventure, the party found a magic sword:

We found a magic sword on the ground. […] one of the players tried to pick it up. He received a shock and was thrown across the room. The same thing happened to the second player to try. When Bill tried to pick it up he was successful. We were all impressed and Dave declared Bill our leader and elevated him to “hero” status. [17]

Since the players found a magic sword during the first dungeon adventure, the “Magic Swords” material almost certainly must have existed by Svenson’s Christmas break of 1970-71. Since Chainmail was not published until approximately May of 1971,[18] and Arneson’s “Magic Protection Points” material includes material from Chainmail’s Fantasy Supplement, the order given by Arneson and Svenson (which was confirmed by a third player) would be 1) the “Magic Swords” material, 2) Chainmail, and 3) the “Magic Protection Points” material—the same order given by Case C in section 3.

4.2 Case C is Consistent with Arneson’s Dating of the “Magic Swords” Material

Arneson said in an introduction to the Magic Swords section (p. 64) of The First Fantasy Campaign:

Prior to setting up Blackmoor I spent a considerable effort in setting up an entire family of Magical swords. The swords, indeed comprise most of the early magical artifacts. [19]

If the “Magic Swords” material predated Blackmoor, it would predate the “Magic Protection Points” material; this is consistent with Case C.

4.3 Case C is Consistent with “Lycanthrope” Frequently Appearing in The First Fantasy Campaign

“Lycanthrope” appears 25 times in The First Fantasy Campaign, while “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” only appear once (in the “Magic Swords” material). This suggests that “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” were only used for a short period of time, while “Lycanthrope” was used for a much longer period of time. As shown in Case 3’s Table 3, “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” would have been Arneson’s early creature names, which Arneson soon replaced with Gygax’s “Lycanthrope” grouping term for Werebears and Werewolves after he began using Chainmail. Therefore, Arneson would have used “Were Bear” and “Were Wolf” for less than a year (no longer than from when he first encountered Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth” to when he started using Chainmail), while he would have used the term “Lycanthrope” for years. Arneson noted on page 87 of The First Fantasy Campaign that the Bleakwood section “was for special convention demonstrations but was only used at Gencon VIII”; Gen Con VIII took place in August of 1975, demonstrating that The First Fantasy Campaign includes material from years of play (during most of which Arneson appears to have used the term “Lycanthrope,” thus accounting for its great frequency in The First Fantasy Campaign compared to “Were Bears” and “Were Wolves”)

5 What Arneson May Have Sent to Gygax

Based on the above analysis, Arneson appears to have sent Gygax material that included all the creature names from the “Magic Swords” material appearing in The First Fantasy Campaign. Note that this does not necessarily mean that Arneson actually sent Gygax the “Magic Swords” material; the creature names and powers from the “Magic Swords” material could have also been included in a list of creature descriptions or in table similar to the Fantasy Reference Table instead. However, since Gygax did include magic swords in Chainmail, whereas Patt had not included them in “Rules for Middle Earth,” Arneson almost certainly included some material at least referencing magic swords with the material that he sent to Gygax.

Arneson having a list of creature names in the “Magic Swords” material implies that he also had some game-related information to go along with those creature names, such as stats and/or descriptions. Assuming that this is the case, Gygax likely incorporated much of that material into Chainmail after editing it (this is what Gygax appears to have done with material he incorporated into Chainmail from both Domesday Book and from Patt’s “Rules for Middle Earth”). Therefore, Arneson’s material in Chainmail is likely to be largely intact, and this appears to be supported by the creature names from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appearing in Gygax’s Fantasy Supplement largely verbatim. Arneson also provided a list of abilities in the “Magic Swords” material:

Cause Morale Check

Combat Increase

Evil Detection

Intelligence Increase

Invisibility

Invisibility Detection

Magic Ability

Magic Detection

Paralize

Raise Morale

See in Darkness

Strength

Just as in the case of creature names, these appear verbatim or nearly verbatim in both the creature descriptions and in the Fantasy Reference Table. For example, the Wraith creature description reads:

"WRAITHS (Nazgul etc.): Wraiths can see in darkness, raise the morale of friendly troops as if they were Heroes, cause the enemy to check morale as if they were Super Heroes, and paralize any enemy man […]"

The Fantasy Supplement is comprised of three parts: 1) creature descriptions, 2) the Fantasy Reference Table, and 3) the Fantasy Combat Table. It appears likely that Arneson sent Gygax earlier versions of all three of them.

5.1 Creature Descriptions

Arneson included a set of creature descriptions at the back of The First Fantasy Campaign that are similar to those in Chainmail. They appear to date sometime between when he started using Chainmail and when D&D was published (since they include material from Chainmail but not D&D). This alone doesn’t indicate that Arneson probably sent Gygax creature descriptions, but there is another piece of evidence indicating that he probably did: the “Giant” entry is missing from the creature descriptions of Chainmail, but included on both the Fantasy Reference Table and the Fantasy Combat Table. Since the ATTACK and DEFEND stats for using the Giant with the mass-combat rules of Chainmail were listed as “Special” (see Figure 4), Gygax would have needed to have specified them in the creature description for the Giant (just like the other creatures listed as “Special”). However, Arneson had no such need, and likely would not have bothered with writing a creature description for the Giant (which was simply a large human). Supporting this is the fact that the Giant is the only creature listed on the Fantasy Reference Table with no special ability. Therefore, what appears likely to have happened is that Gygax prepared his creature descriptions from a set of creature descriptions that Arneson had provided and simply didn’t notice that Arneson had not provided a creature description for the Giant. If Gygax had written his creature descriptions based on the earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table that Arneson appears to have sent him (see below), he likely wouldn’t have omitted the Giant, since it appears to have been listed there. Therefore, it appears that Arneson gave Gygax creature descriptions. Arneson’s creature descriptions almost certainly would have included ability names that he had also listed in his “Magic Swords” material (e.g., see the Wraith description above). Gygax likely then expanded them into the creature descriptions seen in the Fantasy Supplement.

Figure 4: A portion from the Fantasy Reference Table

5.2 Fantasy Reference Table

The Fantasy Reference Table (see Figure 5) bears a resemblance to the “Figure Characteristics” table from Arneson’s and Hoffa’s 1969 ruleset Strategos A (see Table 4); a reformatted version of the Strategos A table is shown as Table 5 (compare Table 5 to Figure 5). Arneson’s original reference table that he appears to have sent to Gygax likely didn’t include the last two columns of ATTACK and DEFEND stats for using the fantasy creatures with the mass-combat rules of Chainmail; Gygax appears to have added those. When Table 4 from Strategos A is reformatted slightly, it more closely resembles the Fantasy Reference Table (compare Figure 5 and Table 5 below).

Additional evidence that Arneson sent Gygax an earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table is shown in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, the first six abilities on the Fantasy Reference Table appear to have a corresponding ability in the list of abilities included in the “Magic Swords” material of The First Fantasy Campaign. Since Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material appears to predate the Fantasy Supplement per the analysis in section 3, Gygax appears to have drawn the first six abilities on the Fantasy Reference Table from material from Arneson. Given the resemblance of the Fantasy Reference Table to Arneson’s and Hoffa’s Strategos A table, it appears likely that Arneson provided an earlier version of the Fantasy Reference Table that Gygax then drew from.

Table 4: The top of the "Figure Characteristics" table from Arneson's and Hoffa’s Strategos A (1969)

| Type | Melee Value | Protection | Movement (Basic) |

| Hastatii | 3 | 1/9 | 2” Regular, 6” Charge |

| Principes | 3 | 1/9 | same |

| Triarii | 4 | 1/9 | same |

Figure 5: The top of the Fantasy Reference Table from Chainmail

Table 5: A Version of Table 4 Reformatted to Look Like the Fantasy Reference Table in Figure 5

| Type | Movement (Basic) | Melee Value | Protection | Charge |

| Hastatii | 2” | 3 | 1/9 | 6” |

| Principes | 2” | 3 | 1/9 | 6” |

| Triarii | 2” | 4 | 1/9 | 6” |

| Ability from Arneson’s “Magic Swords” material | Abilities from the Fantasy Reference Table of Chainmail |

| Invisibility | A- The ability to become invisible (Hobbits only in brush or woods) |

| See in Darkness | B- The ability to see in normal darkness as if it were light |

| Raise Morale | D- The ability to raise morale of friendly troops |

| Cause Morale Check | E- The ability to cause the enemy to check morale |

| Invisibility Detection | F- The ability to detect hidden invisable enemies |

| Paralize | G- The ability to paralize by touch |

Arneson said:

So we quickly came up with twenty or thirty [monsters]. We tried setting them up in a matrix, but that didn’t work because it was quickly taking up an entire wall. [20]

Although Arneson was likely speaking figuratively regarding “taking up an entire wall,” the problem he appears to have had was that if he included n creatures in his matrix, he’d need to fill out n2 entries in the table. For example, if he had 5 monsters, he’d need to fill out 25 entries; with 10 monsters, 100 entries; with 20 monsters, 400 entries; with 30 monsters, 900 entries. He explained the problem plainly: “The combat matrix became a thing of the past. There were over 30 critters, and the 30x30 matrix became unwieldy.” [21] Arneson’s description of his “combat matrix” clearly matches the format of the Fantasy Combat Table from Chainmail, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: The Fantasy Combat Table from Chainmail

Most of the creatures on the Fantasy Combat Table were likely on Arneson’s original “combat matrix.” The creatures shown on the Fantasy Combat Table that are unique to Chainmail (Lycanthrope, Roc, and Wight), couldn’t have been on Arneson’s original table. Since Arneson didn’t include “Tree” in either the “Magic Swords” or “Magic Protection Points” tables, he likely didn’t include it in the “combat matrix” either.

Gygax included ATTACK and DEFEND stats (see Figure 5) on the Fantasy Reference Table for resolving battles between men and fantasy creatures such as dragons using Chainmail’s mass-combat rules; this appears to be the reason there is no Man entry in the Fantasy Combat Table, nor the humanoids Goblin and Orc. Arneson probably used the term Mortal for Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Hobbits (since Patt’s rules included these races, but no Mortal, while Arneson’s rules included Mortal, but none of the others). Therefore, Arneson’s Fantasy Combat Table likely had a Mortal entry.

Gygax added every creature from Patt’s rules and all but the Ghost, Mortal, and Pudding from Arneson’s. The Mortal, per above, was likely a grouping term for Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Hobbits, and since Gygax effectively included all four (Men being in the other sections of Chainmail), he wouldn’t have needed the Mortal. Gygax may have eliminated Pudding for a variety of reasons (e.g., it wasn’t a creature typically associated with the Fantasy genre). It is more difficult to explain why he didn’t include the Ghost, as he had included the Ghoul. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that Gygax simply changed the name of the Ghost to Wight.

6 References

- Gygax, Gary. “Forward.” Dungeons & Dragons by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, vol. 1 (Men & Magic), Tactical Studies Rules, 1974, p. 3.

- Gygax, Gary. Letter from Gary Gygax to Lee Gold. Alarums & Excursions, No. 2, Jul. 1975, p. unknown.

- Gygax, Gary. Untitled essay. Heroic Worlds by Lawrence Schick, Prometheus Books, July 1991, p. 132.

- Gygax, Gary. "Gary Gygax on Dungeons & Dragons: Origins of the Game." The Dragon, no. 7, June 1977, p. 7.

- Gygax, Gary. "Gary Gygax on Dungeons & Dragons: Origins of the Game." The Dragon, no. 7, June 1977, p. 7.

- Patt, Leonard. “Rules for Middle Earth.” The Courier, vol. 2, no. 7, c. Nov. 1970.

- “A Precursor to the Chainmail Fantasy Supplement.” Blogspot, 20 Jan. 2016, playingattheworld.blogspot.com/2016/01/a-precursor-to-chainmail-fantasy.html

- Gygax, Gary. Role-Playing Mastery. Perigee Books, 1987, pp. 19-20.

- Gygax, Gary. “The Ultimate Interview with Gary Gygax.” dungeons.it, circa 2002, reprinted at www.keithrobinson.me/thekyngdoms/interviews/garygygax.php

- Gygax, Gary. Gary Gygax Interview. GameBanshee.com, Mar. 2, 2009, www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.gamebanshee.com%2Finterviews%2Fgarygygax1.php&date=2009-03-02

- Arneson, Dave. Untitled essay. Heroic Worlds by Lawrence Schick, Prometheus Books, July 1991, pp. 166-167.

- Arneson, Dave. “Upcoming Club News,” Corner of the Table, Apr. 1971, p. 4.

- Arneson, Dave. The First Fantasy Campaign Playing Aid. Judges Guild, 1977, p. 42.

- Svenson, Greg. “The First Dungeon Adventure.” The Blackmoor Archives, 21 May 2009, blackmoor.mystara.net/greg01.html

- Svenson, Greg. “The First Dungeon Adventure.” The Blackmoor Archives, originally published in 2006, revised on 21 May 2009, blackmoor.mystara.net/greg01.html

- Svenson, Greg. “Re: Set of questions #2.” Received by Michael Wittig, 14 Aug. 2018.

- Svenson, Greg. “The First Dungeon Adventure.” The Blackmoor Archives, 21 May 2009, blackmoor.mystara.net/greg01.html

- Lowry, Don. Copyright Application for “Chainmail Rules for Medieval Miniatures,” signed 31 Dec. 1971.

- Arneson, Dave. The First Fantasy Campaign Playing Aid. Judges Guild, 1977, p. 64.

- Arneson, Dave. “Dave Arneson Interview” by Harold Foundary, Digital Entertainment News, 15 Mar. 2004, web.archive.org/web/20110710130445/http:/www.dignews.com/platforms/xbox/xbox-features/dave-arneson-interview-feature/

- Arneson, Dave. “BLACKMOOR.” circa 1998. Microsoft Word file.

Last edited by a moderator: