Iosue

Legend

The surprise hit of Sword World RPG in 1989 had two notable effects. For one, there was a notable explosion of games, from a wide variety of publishers. 1989 saw the release of six new RPGs, which was pretty par for the course since 1985. In 1990, that number doubled, with only five coming from the established RPG publishers. In 1991, the number swelled to 21. To 26 in 1992. This was the high water mark, but even 1993 saw 18 new RPGs, and 1994 saw 17.

Despite this boom in the industry, Sword World RPG’s dominance as the most popular RPG, indeed the most popular fantasy RPG put Shinwa in a tough position. All new players were going to the much cheaper, much more aesthetically familiar Sword World, and Shinwa could no longer justify the expense of putting out five different box sets for D&D. In 1991, they attempted to pivot to 2nd Edition AD&D. As with D&D, the books were faithfully reproduced, in Japanese, with the same layout and trade dress as the American books. It was a complete disaster. No one playing D&D made the switch, let alone anyone playing Sword World. Shinwa suspended operations in 1992. Over the course of 1993-1994, they declared bankruptcy.

Drama of quite a different sort was unfolding over at Kadokawa. While a major publishing house in Japan, Kadokawa was still family run. Genyoshi Kadokawa founded the company in 1945, and his son Haruki took over as the CEO in 1975. Though the oldest son and heir, Haruki was less interested in running a publishing company than he was being a filmmaker. He set up a film production division in Kadokawa, and tried to break into Hollywood. This ended up with the Kadokawa company taking on lots of debt. Haruki’s younger brother, Tsuguhiko, was a vice-president in the company, and had a much better head for the publishing business. There was a power struggle, and in September of 1992, Tsuguhiko left Kadokawa, taking with him a few key personnel in the main office, and the entire workforce of the subsidiary Kadokawa Media Office. They set up a new publishing company: MediaWorks. MediaWorks began creating magazines to compete with all of Kadokawa’s offerings.

I have to warn you here, a sudden left-turn is coming. Just as MediaWorks got its magazines up and running, Tsuguhiko’s older brother Haruki, the CEO of Kadokawa...was arrested for smuggling cocaine. The Kadokawa board immediately invited Tsuguhiko to become CEO. He also remained CEO of MediaWorks And MediaWorks remained an independent company for the next 9 years.

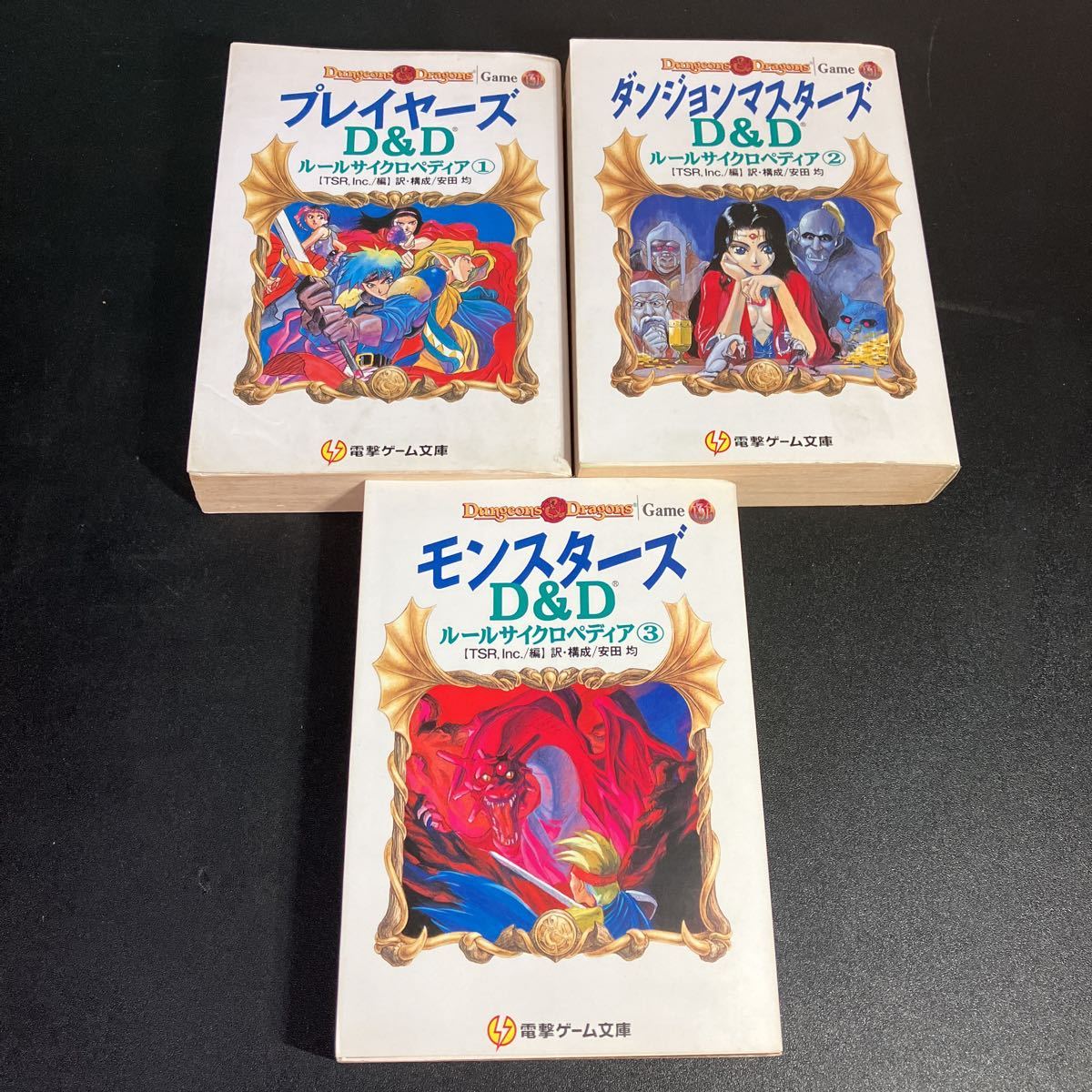

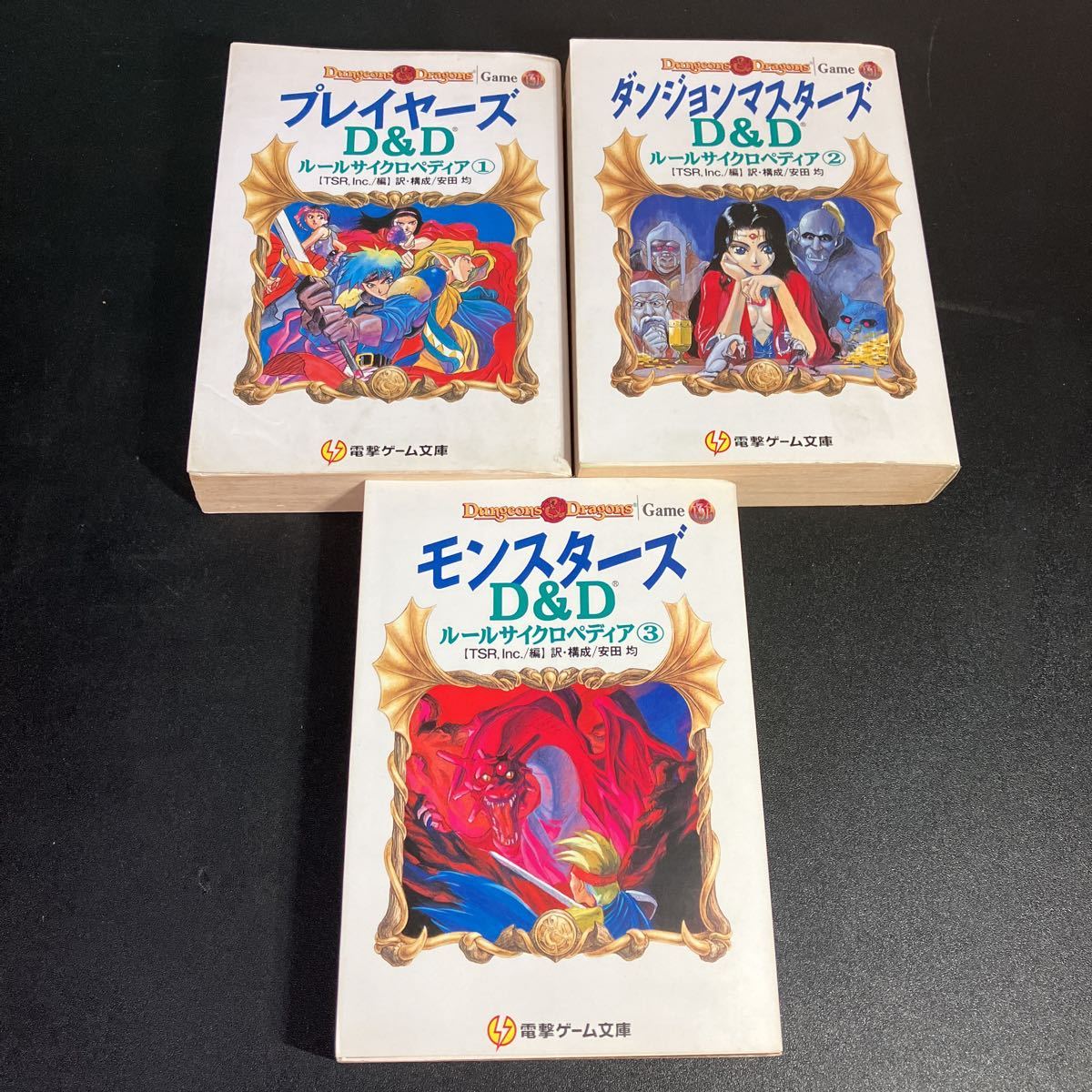

And now to bring it full circle. Shinwa loses all its hit points in 1994, and who is there to steal its stuff, specifically the D&D license? MediaWorks, that’s who. At this point, the Rules Cyclopedia had been published by TSR, so MediaWorks decided that instead of copying the American products, they would localize it with the proven model for RPG sales: the bunko format, with anime-style art. And Tsuguhiko knew who to go to for the translation; the same man he’d gone to for Dragonlance: Hitoshi Yasuda.

The localized bunko Rules Cyclopedia

The other significant release of this era was GURPS in 1992, translated by Group SNE, and published by Kadokawa. At this time, Kadokawa had started Comp RPG, a quarterly off-shoot of Comptiq devoted only to RPGs, and GURPS was prominently featured. In particular, Group SNE wrote two novels, The Damned Stalkers (horror) and Runal Saga (fantasy), and then released GURPS supplements based on these.

In general, “generic” or “universal” systems were the taste of the day in early 1990s Japan. That said, these were generally less in the mold of GURPS, letting players play in whatever genre they wanted, but rather more in the vein of Chaosium’s Basic Roleplaying: a generic system chassis on which the designers could build new games. I mentioned WARPS in the previous installment. Adventure Planning Service had its Apple Basic system. Fujimi Shobo developed MAGIUS (Multiple Assignable Game Interface for Universal System) in 1985.

Speaking of generic systems, one innovator of such systems in the 2000s would be Far East Amusement Research (F.E.A.R.), which was established in 1993. Not unlike Yuentai, F.E.A.R. was made up Tokyo-based freelance game designers, writers, translators, and creators who decided to band together. Many had written for Shinkigensha’s “Truth in Fantasy” series in the late 1980s. F.E.A.R. stated their intentions clearly with their debut RPG Tokyo @ Nova. Set in a post-apocalyptic near future, the game did not assume cooperative play by the players, nor did it use dice. Instead, checks were handled by choosing cards from one’s hand. Bold moves, given the popular systems at the time, but it did well enough for F.E.A.R. to A) establish the company, and B) remain in print and supported to this day.

Along with the glut of RPGs came a glut of RPG-related magazines. Kadokawa had Comp RPG (prominently featuring GURPS and Group SNE’s innovations for Tunnels and Trolls, among others), ASCII had LOGOUT (featuring Wizardry RPG and Ghost Hunter RPG), Mediaworks had Dengeki Adventures (featuring D&D, Earthdawn, and Crystania), and Kadokawa’s Fujimi Shobo imprint had RPG Dragon (featuring Sword World, and Shadowrun).

The bubble economy had started to deflate in 1992, though it took a while for people to really feel the effects. But new RPG releases dropped precipitously in 1995, with only 11. And other developments were afoot. In 1994, Tsuguhiko Kadokawa invited Hitoshi Yasuda to go with him to GenCon, where he was going to endeavor to get the license for the Japanese release of Magic: The Gathering. After a number of negotiations, the license ultimately went to Hobby Japan. Kadokawa and Yasuda returned to Japan disappointed, but neither quite realized what this portended for the RPG industry. In April of 1996, Hobby Japan released the Japanese version of Magic: the Gathering. In the fall of that same year, the Pokemon Trading Card Game was released. It was like a bomb, two bombs in fact, had gone off in the hobby industry.

Next Part – The Winter Age

Despite this boom in the industry, Sword World RPG’s dominance as the most popular RPG, indeed the most popular fantasy RPG put Shinwa in a tough position. All new players were going to the much cheaper, much more aesthetically familiar Sword World, and Shinwa could no longer justify the expense of putting out five different box sets for D&D. In 1991, they attempted to pivot to 2nd Edition AD&D. As with D&D, the books were faithfully reproduced, in Japanese, with the same layout and trade dress as the American books. It was a complete disaster. No one playing D&D made the switch, let alone anyone playing Sword World. Shinwa suspended operations in 1992. Over the course of 1993-1994, they declared bankruptcy.

Drama of quite a different sort was unfolding over at Kadokawa. While a major publishing house in Japan, Kadokawa was still family run. Genyoshi Kadokawa founded the company in 1945, and his son Haruki took over as the CEO in 1975. Though the oldest son and heir, Haruki was less interested in running a publishing company than he was being a filmmaker. He set up a film production division in Kadokawa, and tried to break into Hollywood. This ended up with the Kadokawa company taking on lots of debt. Haruki’s younger brother, Tsuguhiko, was a vice-president in the company, and had a much better head for the publishing business. There was a power struggle, and in September of 1992, Tsuguhiko left Kadokawa, taking with him a few key personnel in the main office, and the entire workforce of the subsidiary Kadokawa Media Office. They set up a new publishing company: MediaWorks. MediaWorks began creating magazines to compete with all of Kadokawa’s offerings.

I have to warn you here, a sudden left-turn is coming. Just as MediaWorks got its magazines up and running, Tsuguhiko’s older brother Haruki, the CEO of Kadokawa...was arrested for smuggling cocaine. The Kadokawa board immediately invited Tsuguhiko to become CEO. He also remained CEO of MediaWorks And MediaWorks remained an independent company for the next 9 years.

And now to bring it full circle. Shinwa loses all its hit points in 1994, and who is there to steal its stuff, specifically the D&D license? MediaWorks, that’s who. At this point, the Rules Cyclopedia had been published by TSR, so MediaWorks decided that instead of copying the American products, they would localize it with the proven model for RPG sales: the bunko format, with anime-style art. And Tsuguhiko knew who to go to for the translation; the same man he’d gone to for Dragonlance: Hitoshi Yasuda.

The localized bunko Rules Cyclopedia

The other significant release of this era was GURPS in 1992, translated by Group SNE, and published by Kadokawa. At this time, Kadokawa had started Comp RPG, a quarterly off-shoot of Comptiq devoted only to RPGs, and GURPS was prominently featured. In particular, Group SNE wrote two novels, The Damned Stalkers (horror) and Runal Saga (fantasy), and then released GURPS supplements based on these.

In general, “generic” or “universal” systems were the taste of the day in early 1990s Japan. That said, these were generally less in the mold of GURPS, letting players play in whatever genre they wanted, but rather more in the vein of Chaosium’s Basic Roleplaying: a generic system chassis on which the designers could build new games. I mentioned WARPS in the previous installment. Adventure Planning Service had its Apple Basic system. Fujimi Shobo developed MAGIUS (Multiple Assignable Game Interface for Universal System) in 1985.

Speaking of generic systems, one innovator of such systems in the 2000s would be Far East Amusement Research (F.E.A.R.), which was established in 1993. Not unlike Yuentai, F.E.A.R. was made up Tokyo-based freelance game designers, writers, translators, and creators who decided to band together. Many had written for Shinkigensha’s “Truth in Fantasy” series in the late 1980s. F.E.A.R. stated their intentions clearly with their debut RPG Tokyo @ Nova. Set in a post-apocalyptic near future, the game did not assume cooperative play by the players, nor did it use dice. Instead, checks were handled by choosing cards from one’s hand. Bold moves, given the popular systems at the time, but it did well enough for F.E.A.R. to A) establish the company, and B) remain in print and supported to this day.

Along with the glut of RPGs came a glut of RPG-related magazines. Kadokawa had Comp RPG (prominently featuring GURPS and Group SNE’s innovations for Tunnels and Trolls, among others), ASCII had LOGOUT (featuring Wizardry RPG and Ghost Hunter RPG), Mediaworks had Dengeki Adventures (featuring D&D, Earthdawn, and Crystania), and Kadokawa’s Fujimi Shobo imprint had RPG Dragon (featuring Sword World, and Shadowrun).

The bubble economy had started to deflate in 1992, though it took a while for people to really feel the effects. But new RPG releases dropped precipitously in 1995, with only 11. And other developments were afoot. In 1994, Tsuguhiko Kadokawa invited Hitoshi Yasuda to go with him to GenCon, where he was going to endeavor to get the license for the Japanese release of Magic: The Gathering. After a number of negotiations, the license ultimately went to Hobby Japan. Kadokawa and Yasuda returned to Japan disappointed, but neither quite realized what this portended for the RPG industry. In April of 1996, Hobby Japan released the Japanese version of Magic: the Gathering. In the fall of that same year, the Pokemon Trading Card Game was released. It was like a bomb, two bombs in fact, had gone off in the hobby industry.

Next Part – The Winter Age

Last edited: