Yaarel

🇮🇱 🇺🇦 He-Mage

One feature that distinguishes the arrival of the Early Viking Period is the widespread use of high quality steel. The Norse are typically proficient with metalworking. Most make their own tools from steel bars. It is also common to recycle steel from earlier items. Talented metalworkers are in demand and enjoy high social status. Those who can produce consistently good steel from raw iron ore can amass wealth.

Analogous to the high quality fabrics and clothing, the Norse excel in craftsmanship, including metalwork, woodwork, and other high-skill labors. Esthetic values prefer goods that are effective, look good, and last across generations. Heh, Nordic lands have long winters. Finding something useful to do helps to pass the time.

Nordic lands are rich in iron deposits. During the Viking Period, mining for iron is known. But most iron comes from wetland peat bogs, where anaerobic microorganisms concentrate the iron molecules that wash down from the mountain rivers, to form iron ‘bog ore’.

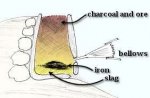

A stone protector insulates the bellows from the heat of the furnace.

Examples of a ‘bloom’ of steel from a furnace.

Furnaces of various sizes are known. Archeologists are still puzzling out the metallurgy of the Viking Period. Yet the following is clear enough, and modern experiments can repeat the processes. The results produce high quality steel that compares somewhat to archeological remains. The experiments suggest metalworkers have control over the amount of carbon in the steel.

To make steel, the metalworker builds a furnace out of clay, sand, and fiber-rich dung. The mixture is highly effective for the furnace walls and insulates well. The smelter supplies iron ore and coal thru the top of the furnace. Bellows blow air periodically into the lower half of the furnace to intensify the heat of the fire. The slag liquefies away from the iron, flows to the bottom of the furnace, cools along the walls, forming a bowl. The steel ‘bloom’ collects in this bowl. The bloom is molten but nonliquid, and ideally welds together to resemble a fiery sponge. Normally, the bottom of the clay furnace is broken open to extricate the bloom.

The metalworker hammers and folds the bloom to manually squeeze out any inclusions and consolidate the steel mass. Ideally, even specs barely visible to eye must be removed.

Afterward, the bloom can ‘quench’ (in water, oil, or other liquid) to rapidly cool to make it harder it, but then ‘temper’ in moderate heat to soften the hard but brittle textures to make it tougher.

The process of making steel is complex, and the same methods that can improve the quality of the steel can also harm it.

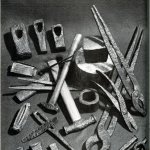

Metalwork is typically outdoors and low to the ground. Metalworkers squat and kneel while working. Normally a larger stone bolder with a suitably smooth work area serves as the anvil. But a small iron anvil on an upright stout log is also known. A wooden box carries the iron tools, including hammer, tongs, file, and so on. Thus the equipment for metallurgy is easily portable. For example, the vikings in Canada needed new iron nails to repair their ship. So they found iron ore locally in a bog there, built a clay furnace to smelt it, and forged the nails into shape on a large stone.

Here is the stone anvil of a famous metalworker in Iceland, who pulled it out from ocean floor.

Norse steel is medium-carbon steel, with the percentage of carbon ranging from about 0.4% to 0.7%. There is also Norse iron that is low-carbon about 0.2% to 0.4%. Lower carbon tends to be softer but tougher (but impurities and inclusions can make it brittle). Higher carbon tends to be hard but brittle.

The minute presence of carbon, the high heat while the bloom forms, the quenching, and possibly other processes, imbue molecular structures in the iron (pearlite, martensite, cementite) that can make steel dramatically harder.

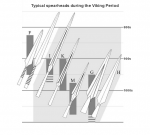

The Norse metalworker employs pattern welding, welding together sheets of alternating higher and lower carbon, then folding and twisting the layers. The final steel is high quality, both hard and tough, and forms esthetic patterns of light and dark.

For an item such as the sword, the body of the blade predominates the lower carbon for toughness, while the sharp edges welded on separately on each side, predominate the higher carbon for hardness. Note the separate patterns in the blade along the central fuller and along each edge.

The Norse of the Viking Period made good steel.

Last edited: