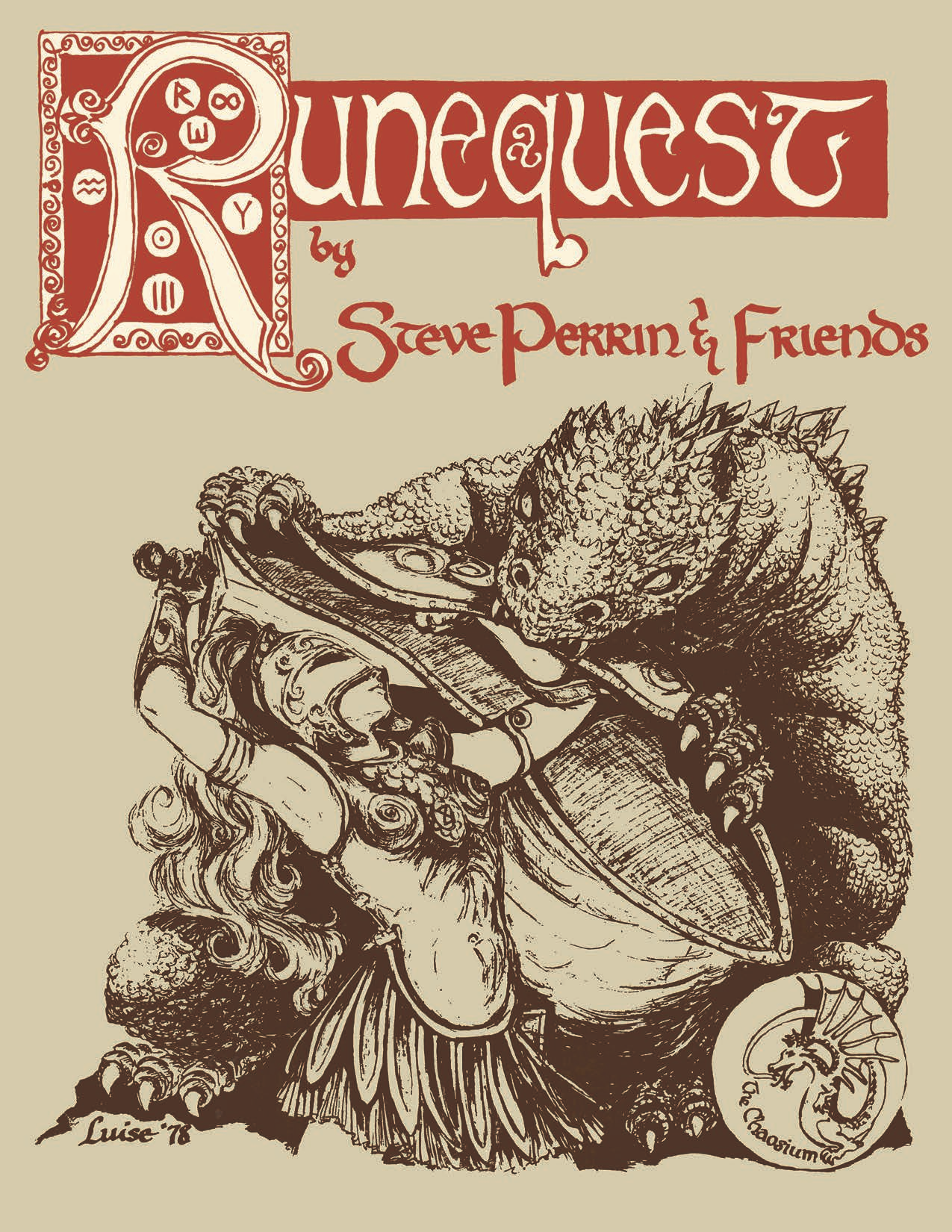

For the RuneQuest Classic Kickstarter in 2016 Steve Perrin generously provided a personal account of his role in the genesis of the RuneQuest roleplaying game. Although at the time of the Kickstarter we publicly featured an excerpt of Steve's recollections, the full account was only ever published a high level backer item (in the RuneQuest Playtest Manuscript) and so only received limited circulation.

In memory of Steve, here we present his account in full as a six part series, offering his fascinating insights into the development of RuneQuest, the rules that cemented Steve Perrin as one of the most influential game designers of all time.

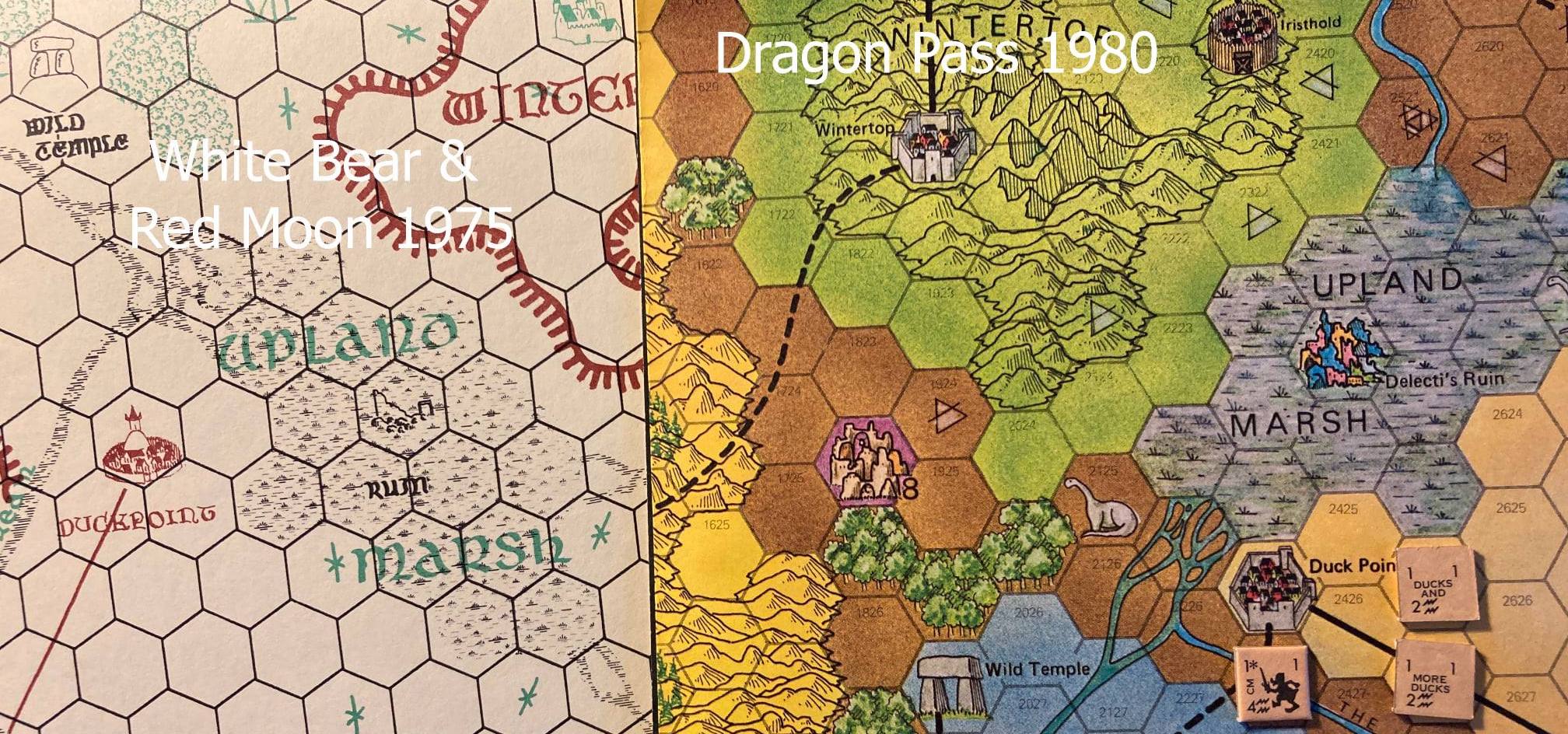

The game’s format was similar to the war games put out by Avalon Hill and Strategic Simulations, with a hex map and cardboard pieces for the army groups (actually card stock for the first edition, which made for some fun storage and unit-stacking problems). But instead of the usual modern military designations for infantry and artillery and cavalry, each piece was decorated with Runes, each tied to the type of unit it was supposed to be. The runes were an interesting conflation of futhark, American Indian symbology, and a few from other sources.

Greg moved in the same science fiction fan circles I did, but our paths had not crossed. I was mostly involved with the Society for Creative Anachronism, which was really just starting to go national at the time. Greg was not part of that group. So despite mutual friends and acquaintances we had not met.

Yet.

Greg and I met physically at a D&D game a few months later. My friend and fellow wargamer Clint Bigglestone ran into him at a fan party and invited him to be a guest at one of our regular Monday night D&D games. Greg invited our group to come help playtest his Nomad Gods game, a sequel to White Bear & Red Moon set in the neighboring desolate Plains of Prax. I began to appreciate just how much creative energy he had put into these games, and the world of Glorantha they were set in.

Various members of our group, significantly Steve Henderson and Clint Bigglestone, and I helped with the playtesting of Nomad Gods. When Jeff Pimper and I conceived of All the Worlds Monsters, we went to Greg for advice on how to publish it, and he offered to take care of publishing it – taking some of the burden off of us and giving him more items to put in his catalog.

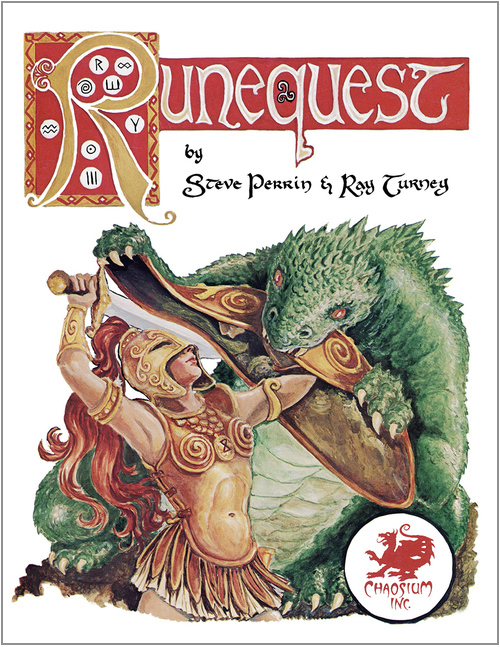

Meantime, Greg thought he needed a role-playing version of Glorantha and looked about for someone to write it for him. For a while Dave Hargrave of Arduin fame attempted to fit Glorantha into his style of game, but the result was still too D&D-ish for Greg’s liking. A trio of gamers in the area, Art and Ray Turney and their friend Henrik Pfeifer offered to come up with a game for him and he gave the go-ahead. After a couple of months, he thought maybe another viewpoint might be useful and he asked me and Clint Bigglestone to take a look at how things were going.

On July 4, 1976, as the United States of America celebrated its 200th anniversary, we were introduced to the first stage of “The Chaosium’s role playing game.” It looked a lot like D&D, with classes and experience points and saving throws, but it had one feature that I immediately picked up on:

Any character can do anything.

In memory of Steve, here we present his account in full as a six part series, offering his fascinating insights into the development of RuneQuest, the rules that cemented Steve Perrin as one of the most influential game designers of all time.

Part One: "The Chaosium’s role playing game”

STEVE PERRIN: I first met Greg Stafford through his board game, White Bear and Red Moon. Greg independently published it out of a small house near the Oakland Airport. It portrayed a fantastic world full of wonderful concepts like the Red Moon’s variable power, Cragspider, Sir Ethilrist’s Black Horse Troopers, Dragonewts, and many others. The game concerned the efforts of the Lunar Empire to conquer legendary Dragon Pass and the brave barbarian warriors of the Kingdom of Sartar.The game’s format was similar to the war games put out by Avalon Hill and Strategic Simulations, with a hex map and cardboard pieces for the army groups (actually card stock for the first edition, which made for some fun storage and unit-stacking problems). But instead of the usual modern military designations for infantry and artillery and cavalry, each piece was decorated with Runes, each tied to the type of unit it was supposed to be. The runes were an interesting conflation of futhark, American Indian symbology, and a few from other sources.

Greg moved in the same science fiction fan circles I did, but our paths had not crossed. I was mostly involved with the Society for Creative Anachronism, which was really just starting to go national at the time. Greg was not part of that group. So despite mutual friends and acquaintances we had not met.

Yet.

Greg and I met physically at a D&D game a few months later. My friend and fellow wargamer Clint Bigglestone ran into him at a fan party and invited him to be a guest at one of our regular Monday night D&D games. Greg invited our group to come help playtest his Nomad Gods game, a sequel to White Bear & Red Moon set in the neighboring desolate Plains of Prax. I began to appreciate just how much creative energy he had put into these games, and the world of Glorantha they were set in.

Various members of our group, significantly Steve Henderson and Clint Bigglestone, and I helped with the playtesting of Nomad Gods. When Jeff Pimper and I conceived of All the Worlds Monsters, we went to Greg for advice on how to publish it, and he offered to take care of publishing it – taking some of the burden off of us and giving him more items to put in his catalog.

Meantime, Greg thought he needed a role-playing version of Glorantha and looked about for someone to write it for him. For a while Dave Hargrave of Arduin fame attempted to fit Glorantha into his style of game, but the result was still too D&D-ish for Greg’s liking. A trio of gamers in the area, Art and Ray Turney and their friend Henrik Pfeifer offered to come up with a game for him and he gave the go-ahead. After a couple of months, he thought maybe another viewpoint might be useful and he asked me and Clint Bigglestone to take a look at how things were going.

On July 4, 1976, as the United States of America celebrated its 200th anniversary, we were introduced to the first stage of “The Chaosium’s role playing game.” It looked a lot like D&D, with classes and experience points and saving throws, but it had one feature that I immediately picked up on:

Any character can do anything.