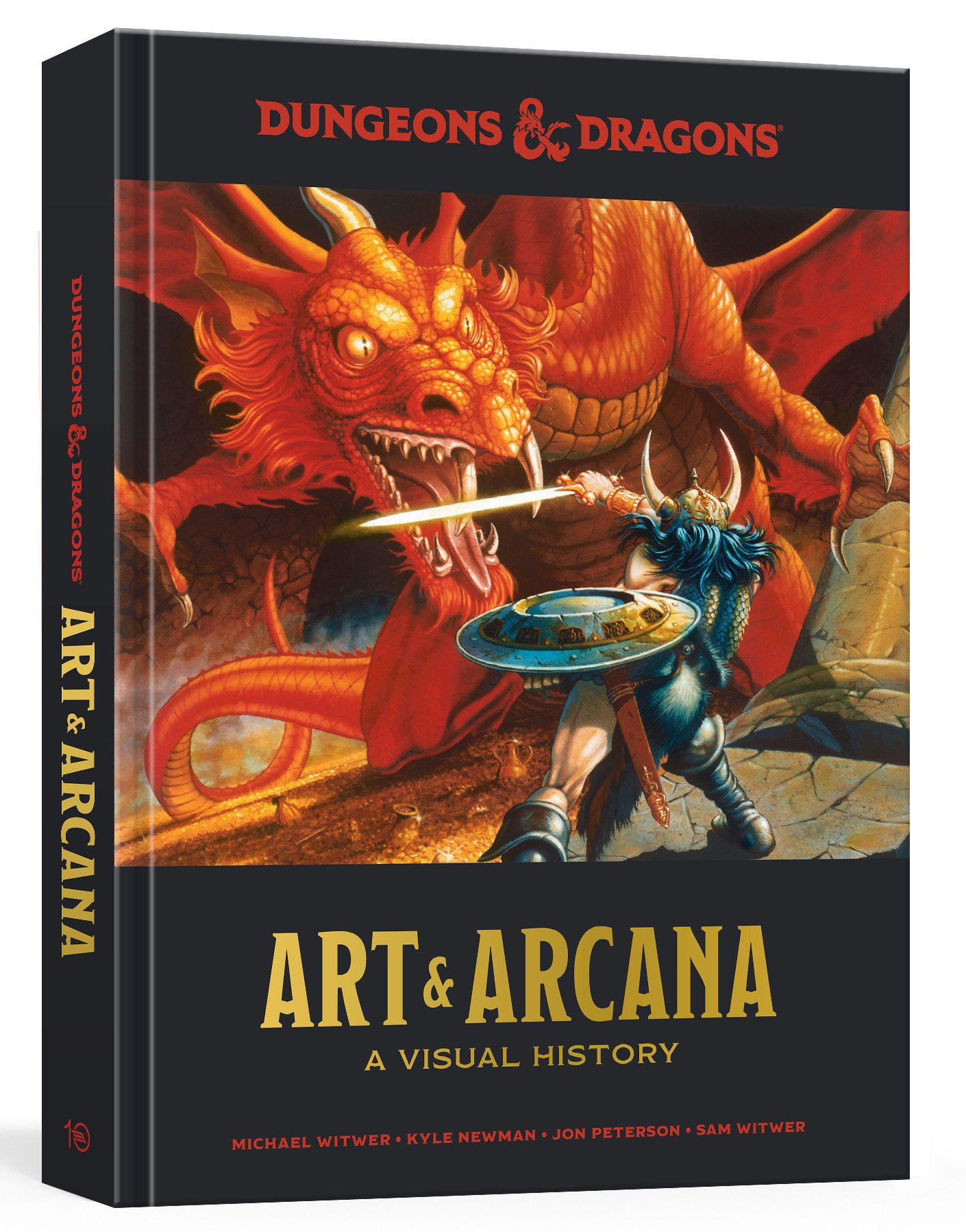

As a long-time Dungeons & Dragons player, I sometimes take for granted just how much tabletop role-playing games elevated fantasy artwork. Whether it was on the cover of D&D boxed sets or in the pages of Dragon Magazine, fantastically-detailed art seemed par for the course. But art tells stories: it shares the outlook of its creators, it expresses thematic differences in editions, and it tells us how to play. Art & Arcana’s greatest achievement is in reminding us why art matters to D&D.

This is no mere coffee table book. The caliber of talent who brought this massive tome to fruition includes directors (Kyle Newman of Fanboys), actors (Sam Witwer of Being Human), writers (Sam’s brother Michael Witwer of Empire of Imagination), and scholars (Jon Peterson of Playing at the World). The combination of artistic and academic talent is the perfect mix for a weighty tome like this.

This is no mere coffee table book. The caliber of talent who brought this massive tome to fruition includes directors (Kyle Newman of Fanboys), actors (Sam Witwer of Being Human), writers (Sam’s brother Michael Witwer of Empire of Imagination), and scholars (Jon Peterson of Playing at the World). The combination of artistic and academic talent is the perfect mix for a weighty tome like this.

Joe Manganiello provides the foreword (because of course he does, Joe’s the new geek-herald of D&D for Hollywood) followed by a clever explanation of how the book is sorted. Art & Arcana is all about exploring unexpected secret passages, and it has plenty: Arteology (the history artists and their favorite art), Deadliest Dungeons (iconic D&D locations), Evilution (the art of iconic D&D monsters), Many Faces Of… (iconic characters), and Sundry Lore (digressions into video and board games, among other topics). Each chapter is named after a spell and assigned to an edition, starting with the basics like Detect Magic for the Original Edition, progressing through Explosive Runes (The Crash of 1983), and Bigby’s Interposing Hand (The Fall of TSR), culminating with Wish (5th Edition). And in case you’re wondering, 4th Edition is referenced as Maze.

Peterson’s influence is felt most in Chapter 1: Detect Magic, where he visually lays out his thesis that Doctor Strange influenced D&D’s art by showing pieces side-by-side from Strange Tales #167. There are juicy bits like the first draft of “Big Eye,” a critter that likely inspired the Beholder and Roper, and a 1974 Eerie Tales panel from Dax the Damned that inspired the warrior on the cover of Supplement I: Greyhawk for Original Dungeons & Dragons (OD&D). The demi-lich Acererak is first of the Many Faces section, but no mention is made of the Ready Player One novel where he featured prominently, or the confusion over Acererak’s true form as a floating skull or the faux-mummy meant to fool adventurers (as depicted by the author of Ready Player One and screenwriter for Newman’s Fanboys, Ernest Cline).

Chapter 2: Pyrotechnics, covers Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ (AD&D) debut. Much attention is paid to Dave Trampier’s 1978 Player Handbook (PHB) cover on pages 78-79, “the instructional foundation of the entire game laid out in a single image.” Curiously, Art & Arcana fails to expand on the visual narrative laid out in later pieces. It’s clear that adventurers murdered a cult of lizard men and stole the gemstone eyes of their idol on the PHB cover. The follow-up to that scene (page 69) graced the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Screen (1979), a full spread by Trampier of the lizardmen getting revenge on the mustachioed warrior depicted in the earlier piece. It’s in this chapter we get to appreciate art that has become staples of the genre, like Emirikol the Chaotic galloping down the street frying people with spells, or a Paladin in Hell doing what paladins do best.

We also learn how James Dallas Egbert III’s disappearance triggered the Satanic Panic against D&D, but there’s a missed opportunity in explaining the series of events that led to the deception, glossed over with the words “he had simply run away to escape academic pressures and other personal problems.” The movie and book that inspired it, Mazes & Monsters, gets a pass too, showing up in a much later chapter (page 147) despite being chiefly responsible for conflating the public’s perception about D&D. In fact, this chapter makes a compelling argument that D&D didn’t help itself with artwork that gleefully engaged in pulp-style, uncensored nudity and demonic imagery. Attempts to clean up the brand with the kid-friendly Morley the Wizard were poorly received by TSR staff, as evidenced by the doodle by art director Jim Roslof showing him stabbing a child.

Attention is also paid to the beautiful cartography of D&D, beginning with co-creator of D&D, Gary Gygax’s World of Greyhawk folio. There’s no mention of Gygax’s other incarnations of Greyhawk's world, Oerth, like Yarth as detailed in his Sagard the Barbarian books, but that’s understandable given the space considerations. This chapter is also where we see the Many Faces of…Lolth, which creates a curious juxtaposition in how she was reimagined from a spider with a woman’s head right up to 1981 when she transformed into a spider-centaur with the upper torso of a female drow. This is at odds with how a drider's form was depicted as punishment by Lolth, and it exemplifies the radical changes heralded by the Fourth Edition in 2001.

Like so many themes in Art & Arcana, the pictures tell their own story through mere juxtaposition. There are many other gorgeous spreads that can only be appreciated in a book like this. You haven’t experienced the cover of the original Fiend Folio until you see the full spread in Art & Arcana.

Chapter 3: Explosive Runes covers D&D’s massive transmedia empire in comics, books, cartoons, and toys that ultimately led to Gygax’s tussle with the Blume brothers over ownership of the company. It culminated in Lorraine Dille Williams ascending to an executive role and Gygax’s ouster, but little mention is made of the Buck Rogers franchise she pushed through TSR’s hype machine. In fact, Art & Arcana credits her with the multimedia approach:

This is also the chapter where we see the Many Faces of…Drizzt. Artists seem to be at a loss as to the color of a drow’s skin. Drizzt’s skin color ranges from brown to gray, to purple, to blue. The most controversial portrayal of drow as people of color, from Queen of the Spiders, isn’t shown.

Chapter 4: Polymorph Self is where we see TSR’s vision for D&D begin to splinter. We get gorgeous visuals of the many world spawned in this era, from Ravenloft to Hollow World to Dark Sun. There’s a missed opportunity to mention the influence of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars series on Dark Sun or Pellucidar on Hollow World, but then the art tells the story better than text ever could.

Chapter 5: Bigby’s Interposing Hand, details the fall of TSR. Art & Arcana creates a clear roadmap of what went wrong, ranging from the failure of Dragon Dice and Spellfire (a competitor to Magic: The Gathering) to the return of hardcover novels from Random House. It places most of the blame on the splintering of the D&D brand, which caused TSR to compete with itself through the creation of multiple game settings:

Chapter 6: Reincarnation, covers TSR’s acquisition by Wizards of the Coast (WOTC) and the rise of Third Edition. There’s a touching picture of a little TSR-style dragon under the umbrella of WOTC, a thank you note showing the company’s appreciation that it was being rescued. This chapter also lightly touches on the lack of diversity in D&D:

There’s unfortunately no mention of the many deaths of Regdar, as expressed through Third Edition’s art. Despite that oversight, Art & Arcana is unsparing when it comes to the D&D films.

Chapter 7: Simulacrum covers 3.5 Edition and the game’s connection to miniatures. It also details the efforts to capture World of Warcraft-style success (D&D’s player base was estimated at four million compared to 12 million of World of Warcraft). D&D’s massive multiplayer efforts were late to the trends it helped spawn, just as it was with collectible card game craze of Magic: The Gathering. Art & Arcana makes the compelling case that the attempts to capture the online gamer market, as we’ve detailed in the past, is what led to Fourth Edition.

Chapter 8: Maze details the rise and fall of Fourth Edition. Its video game biases are reflected in the artwork:

There’s passing reference of WOTC’s shift from the Open Game License to the Game System License due to a “glut of low-quality d20 products” that “undermined consumer confidence in non-Wizards products, such as adventure modules that were essential to supporting the brand.” Like The Book of Erotic Fantasy.

There are also signs of WOTC beginning to appreciate the nostalgia of its fans, with reproductions and retrospectives that catered to the foundational fanbase of a new edition that didn’t care much about video games.

Chapter 9: Wish wraps things up with Fifth Edition. It juxtaposes the retro-style ad of Critical Role (page 420) with the original that inspired it on page vi. The ad sums up the state of D&D today: the kids of yesteryear are all grown up and have returned to their hobby, only now they have the Internet and more money. The book concludes with a tale of a bidding war over an original boxed set of D&D selling for $20,000.

Art & Arcana is the kind of book we didn’t know we needed: a gorgeous, thorough retrospective that will dazzle your adult eyes with visions you never appreciated as a kid. While it doesn’t quite venture into the deepest dungeons of D&D’s past, it has more than enough treasure for any fan to enjoy. I'll cover the Special Edition in a future installment.

Joe Manganiello provides the foreword (because of course he does, Joe’s the new geek-herald of D&D for Hollywood) followed by a clever explanation of how the book is sorted. Art & Arcana is all about exploring unexpected secret passages, and it has plenty: Arteology (the history artists and their favorite art), Deadliest Dungeons (iconic D&D locations), Evilution (the art of iconic D&D monsters), Many Faces Of… (iconic characters), and Sundry Lore (digressions into video and board games, among other topics). Each chapter is named after a spell and assigned to an edition, starting with the basics like Detect Magic for the Original Edition, progressing through Explosive Runes (The Crash of 1983), and Bigby’s Interposing Hand (The Fall of TSR), culminating with Wish (5th Edition). And in case you’re wondering, 4th Edition is referenced as Maze.

Peterson’s influence is felt most in Chapter 1: Detect Magic, where he visually lays out his thesis that Doctor Strange influenced D&D’s art by showing pieces side-by-side from Strange Tales #167. There are juicy bits like the first draft of “Big Eye,” a critter that likely inspired the Beholder and Roper, and a 1974 Eerie Tales panel from Dax the Damned that inspired the warrior on the cover of Supplement I: Greyhawk for Original Dungeons & Dragons (OD&D). The demi-lich Acererak is first of the Many Faces section, but no mention is made of the Ready Player One novel where he featured prominently, or the confusion over Acererak’s true form as a floating skull or the faux-mummy meant to fool adventurers (as depicted by the author of Ready Player One and screenwriter for Newman’s Fanboys, Ernest Cline).

Chapter 2: Pyrotechnics, covers Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ (AD&D) debut. Much attention is paid to Dave Trampier’s 1978 Player Handbook (PHB) cover on pages 78-79, “the instructional foundation of the entire game laid out in a single image.” Curiously, Art & Arcana fails to expand on the visual narrative laid out in later pieces. It’s clear that adventurers murdered a cult of lizard men and stole the gemstone eyes of their idol on the PHB cover. The follow-up to that scene (page 69) graced the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Screen (1979), a full spread by Trampier of the lizardmen getting revenge on the mustachioed warrior depicted in the earlier piece. It’s in this chapter we get to appreciate art that has become staples of the genre, like Emirikol the Chaotic galloping down the street frying people with spells, or a Paladin in Hell doing what paladins do best.

We also learn how James Dallas Egbert III’s disappearance triggered the Satanic Panic against D&D, but there’s a missed opportunity in explaining the series of events that led to the deception, glossed over with the words “he had simply run away to escape academic pressures and other personal problems.” The movie and book that inspired it, Mazes & Monsters, gets a pass too, showing up in a much later chapter (page 147) despite being chiefly responsible for conflating the public’s perception about D&D. In fact, this chapter makes a compelling argument that D&D didn’t help itself with artwork that gleefully engaged in pulp-style, uncensored nudity and demonic imagery. Attempts to clean up the brand with the kid-friendly Morley the Wizard were poorly received by TSR staff, as evidenced by the doodle by art director Jim Roslof showing him stabbing a child.

Attention is also paid to the beautiful cartography of D&D, beginning with co-creator of D&D, Gary Gygax’s World of Greyhawk folio. There’s no mention of Gygax’s other incarnations of Greyhawk's world, Oerth, like Yarth as detailed in his Sagard the Barbarian books, but that’s understandable given the space considerations. This chapter is also where we see the Many Faces of…Lolth, which creates a curious juxtaposition in how she was reimagined from a spider with a woman’s head right up to 1981 when she transformed into a spider-centaur with the upper torso of a female drow. This is at odds with how a drider's form was depicted as punishment by Lolth, and it exemplifies the radical changes heralded by the Fourth Edition in 2001.

Like so many themes in Art & Arcana, the pictures tell their own story through mere juxtaposition. There are many other gorgeous spreads that can only be appreciated in a book like this. You haven’t experienced the cover of the original Fiend Folio until you see the full spread in Art & Arcana.

Chapter 3: Explosive Runes covers D&D’s massive transmedia empire in comics, books, cartoons, and toys that ultimately led to Gygax’s tussle with the Blume brothers over ownership of the company. It culminated in Lorraine Dille Williams ascending to an executive role and Gygax’s ouster, but little mention is made of the Buck Rogers franchise she pushed through TSR’s hype machine. In fact, Art & Arcana credits her with the multimedia approach:

Lorraine Williams came from a background in managing media properties, and it is unsurprising that she drove TSR to develop campaign settings that could be aggressively marketed and licensed as tabletop game products, novelizations, computer games, and comic books.

This is also the chapter where we see the Many Faces of…Drizzt. Artists seem to be at a loss as to the color of a drow’s skin. Drizzt’s skin color ranges from brown to gray, to purple, to blue. The most controversial portrayal of drow as people of color, from Queen of the Spiders, isn’t shown.

Chapter 4: Polymorph Self is where we see TSR’s vision for D&D begin to splinter. We get gorgeous visuals of the many world spawned in this era, from Ravenloft to Hollow World to Dark Sun. There’s a missed opportunity to mention the influence of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars series on Dark Sun or Pellucidar on Hollow World, but then the art tells the story better than text ever could.

Chapter 5: Bigby’s Interposing Hand, details the fall of TSR. Art & Arcana creates a clear roadmap of what went wrong, ranging from the failure of Dragon Dice and Spellfire (a competitor to Magic: The Gathering) to the return of hardcover novels from Random House. It places most of the blame on the splintering of the D&D brand, which caused TSR to compete with itself through the creation of multiple game settings:

While this “something for everyone” approach serves many businesses well, hobby gaming was still a limited market, and TSR had managed to splinter the Dungeons & Dragons fan base into disparate groups that were playing, in essence, separate games. As a matter of course, when one gaming group committed itself to playing a campaign in Forgotten Realms, for example it was naturally to the exclusion of playing a campaign in Dark Sun and buying the associated products. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was competing not only with other gaming companies, but with itself.

Chapter 6: Reincarnation, covers TSR’s acquisition by Wizards of the Coast (WOTC) and the rise of Third Edition. There’s a touching picture of a little TSR-style dragon under the umbrella of WOTC, a thank you note showing the company’s appreciation that it was being rescued. This chapter also lightly touches on the lack of diversity in D&D:

During the 1970s, Gary Gygax spent years refining and tinkering with the rules, always in an effort to bring balance to the game, sometimes overcompensating where he thought there was potential for unfair advantage, as with supernatural races…In this way, the original game steered player characters away from the seductive, short-term bonuses of non-human characters, always in favor of…bland humanity. The removal of class and race restrictions in 3rd edition set a tone for exciting new combinations, but also sent a strong social message: this game is for everyone, and you can be whatever you want to be.

There’s unfortunately no mention of the many deaths of Regdar, as expressed through Third Edition’s art. Despite that oversight, Art & Arcana is unsparing when it comes to the D&D films.

Chapter 7: Simulacrum covers 3.5 Edition and the game’s connection to miniatures. It also details the efforts to capture World of Warcraft-style success (D&D’s player base was estimated at four million compared to 12 million of World of Warcraft). D&D’s massive multiplayer efforts were late to the trends it helped spawn, just as it was with collectible card game craze of Magic: The Gathering. Art & Arcana makes the compelling case that the attempts to capture the online gamer market, as we’ve detailed in the past, is what led to Fourth Edition.

Chapter 8: Maze details the rise and fall of Fourth Edition. Its video game biases are reflected in the artwork:

Accordingly, isometric perspectives and first-person point-of-views, all common in video games, became signature vantages in 4th edition art. Frames were often overcrowded, sometimes conveying a veritable feast of adrenalized information…Dungeons & Dragons had been reforged into a game system that MMO fans would find familiar.

There’s passing reference of WOTC’s shift from the Open Game License to the Game System License due to a “glut of low-quality d20 products” that “undermined consumer confidence in non-Wizards products, such as adventure modules that were essential to supporting the brand.” Like The Book of Erotic Fantasy.

There are also signs of WOTC beginning to appreciate the nostalgia of its fans, with reproductions and retrospectives that catered to the foundational fanbase of a new edition that didn’t care much about video games.

Chapter 9: Wish wraps things up with Fifth Edition. It juxtaposes the retro-style ad of Critical Role (page 420) with the original that inspired it on page vi. The ad sums up the state of D&D today: the kids of yesteryear are all grown up and have returned to their hobby, only now they have the Internet and more money. The book concludes with a tale of a bidding war over an original boxed set of D&D selling for $20,000.

Art & Arcana is the kind of book we didn’t know we needed: a gorgeous, thorough retrospective that will dazzle your adult eyes with visions you never appreciated as a kid. While it doesn’t quite venture into the deepest dungeons of D&D’s past, it has more than enough treasure for any fan to enjoy. I'll cover the Special Edition in a future installment.