We all have our favorite games, but even the ones we love often have flaws we overlook or imperfections we happily house rule. However, there is one game that I find myself unable to find any flaws in. In my opinion, it is the greatest RPG system ever designed, a masterclass in simple and clean mechanics that smoothly support the game setting. I’m talking about Greg Stafford’s King Arthur Pendragon RPG.

In this article I’ll attempt to back up my rather sweeping statement, and in doing so point out just how cleverly written the Pendragon system is. It’s a game that every game designer should take a look at, as there is a lot to learn from it, from one of our most talented (and now sadly missed) game creators. If you are new to Pendragon I hope this gets you to learn more about it, and ideally play it at some point.

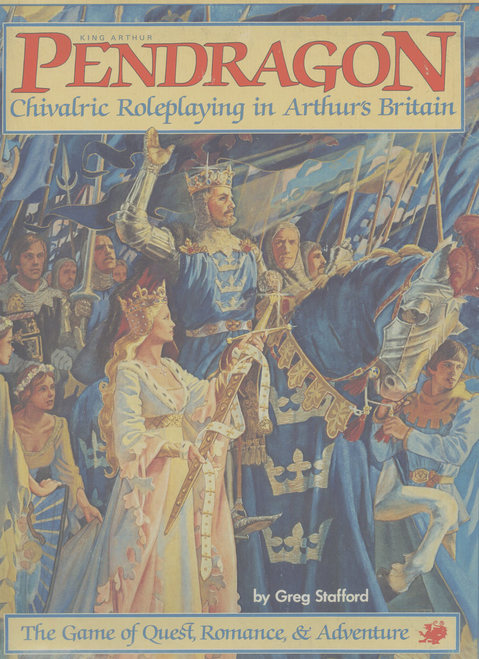

Just in case you are new to Pendragon, I should start with a little detail about the game itself. Pendragon appeared in 1985, in one of Chaosium’s gorgeous boxed sets. The cover by Jodie Lee and interior illustrations by Lisa A Free are among some of the best RPG artwork of the time, and one of the things that initially attracted me to the game. Since its creation, Pendragon has passed through five editions and three different companies, but has remained largely unchanged. The main exception being the 4th edition, which adds a magic system that is potentially usable by player characters.

In Pendragon, your characters are all knights in the era of King Arthur. However, by the era of Arthur we don’t just mean the time he was king. Pendragon comes with a vast and detailed timeline that takes characters from the time before Arthur, through his reign and finally to the tragic fall of his kingdom. Obviously, if your characters are experienced knights by the time the boy-king takes the throne, they’ll be pretty frail and old by the time Mordred leads his army against an aging Arthur. So as characters age they retire, handing the title of player character on to their sons and daughters. When player characters get old and retire, they can leave their land and even some of their reputation to their eldest heir to continue and advance their dynasty. As the campaign progresses, the player characters become richer and more powerful, perhaps even advancing to the Round Table.

Given the character potential of the Middle Ages, a game where you only play knights might seem rather limiting. However, what this allows Pendragon to do is focus on one particular type of character and tailor each adventure specifically for them. While you are a little stuffed if playing a knight doesn’t appeal, there are options for playing ladies and sorcerers, and even female knights (which may be ‘historically inaccurate’, but it’s all based on a myth anyway). However, there is plenty for each knight to do and plenty of variety to create different characters with different strengths.

Pendragon is often (and rightly) lauded for its generational legacy campaign, and its attention to detail in the setting and the myth. The rulebook divides the Arthurian cycle into different phases, and the later supplement ‘the Pendragon Campaign' breaks it down to a year by year guide for all manner of adventure. This alone makes Pendragon quite a unique and well crafted game, making it possible to miss just how good the rules system that underpins everything is.

So, what’s so good about the system? For a start, it is a simple system that doesn’t complicate as situations get more involved. Many simple systems end up adding all manner of bonuses and exceptions to cope with complex actions, but Pendragon manages to avoid that. To make a skill roll you roll 1D20 and have to roll less than your skill level. Roll your actual skill level and you have made a critical. A 20 is a fumble, so when you hit a skill of 20 you can’t fumble anymore. When you are in a contest, such as a swordfight, you need to roll under your skill, but higher than your opponent. Statistics (Strength, Dexterity, etc) make little difference to skills, so everything is encoded in one simple roll, although you might allow the odd bonus or penalty if you like.

Combat is extremely elegant, and not much more involved than a simple opposed roll. You decide who you are fighting and both of you roll your weapon skills. The highest result wins, as long as it is a successful roll and that character gets to damage their opponent (the loser doesn’t). This means you resolve two character’s actions in one roll and do away with any need for initiative, defense pools and actions.

Fighting multiple opponents? Then you have to divide your skill between them, but as evenly or unevenly as you like. So if you have a skill of 16 you might decide to have an effective skill of 8 against each of your two opponents. But you could instead focus on one, applying a skill of 12 against them and leaving only a skill of 4 against the other. Once more, simple, effective and smooth, the system allows players a certain degree of tactics when outnumbered, and ensures large groups of weak bandits can still be a problem for even an experienced group of knights.

In another nice twist, if you don’t beat your opponent (and get to do damage) but still made your roll, you managed to bring your shield into play to gain its armor rating against the damage you are taking. Damage is particularly interesting, as it is not defined by the weapon but the character. Each knight has a damage rating and the weapon they use only modifies that (with a standard sword being the average unmodified roll).

While combat and the basic system is impressive, another unique factor in the game are personality traits. Each character has a collection of 13 positive traits (Chastity, Valor, Honesty etc) and their opposites (Lust, Cowardice, Deceit etc) all rated like skills. The Gamemaster might call for a character to make a roll using one of their traits at any time, such as rolling gluttony to see if they overindulge at a feast. Fail, and they fall to their vice, succeed and the player can decide what the character does.

This might seem like roll playing rather than role playing, but the opposite is true. Many players refuse to let their characters fall to their darker urges, or do things that might embarrass their character. They won’t want to run from a battle and will insist they resist the wiles of a beautiful witch, just because they don’t want their character to fail. But in reality, not everyone is a brave and honest as they would like to be. Even the bravest knights have moments of cowardice, and the most virtuous fall to their vices on occasion. By forcing a personality roll, knights must prove themselves worthy or fail to do so. So if you don’t want your character to be a coward (for instance) you need to put more points in valor. As traits can be improved just like skills, your character can literally learn to be a better person as the game goes on.

However, this doesn’t mean the character is OK with their failings. Often, falling to a vice is what generates role play as the character realizes what they have done and feels a need to atone. For instance, the characters decide to go out for the night, insisting they are only going to have one or two drinks. Then, failing their trait rolls, they get horribly drunk and wake the next morning with a hangover and a feeling of shame for all the things they barely remember doing that night. When the players complain that ‘they said they weren’t going to get drunk’ the Gamemaster replies ‘you said you weren’t intending to, but that’s not what happened’. Just like real life. Given that many of Malory’s Arthurian tales involve knights falling to their desires and having adventures to restore their honor and virtue, it fits the setting perfectly.

While statistics (Strength, Dexterity etc) don’t count towards skills, they still serve a purpose. Statistics are used to calculate the knight’s base damage roll, hit points, how big a wound needs to be to count as a major wound and when they might fall unconscious etc. While statistics are important, the values don’t make a lot of difference unless they are especially high or low. This is an advantage, as when characters get old their statistics begin to drop, slowly but surely. Eventually this is what forces them to retire, despite their expert skills, as their damage and hit points quietly go down until they just aren’t fit enough to carry on adventuring.

I could go on for longer about the simple elegance of the Pendragon system, but I should let you discover the rest for yourself. In my game we constantly think of situations we expect the system to have a problem coping with. But time and again it proves us wrong, no matter how obscure what we are trying to do is. John Wick once coined ‘Stafford’s Law’ that states “If you think you have just had an amazing idea for an RPG system, chances are Greg Stafford thought of it first”. Nowhere is this more evident than in Pendragon.

In this article I’ll attempt to back up my rather sweeping statement, and in doing so point out just how cleverly written the Pendragon system is. It’s a game that every game designer should take a look at, as there is a lot to learn from it, from one of our most talented (and now sadly missed) game creators. If you are new to Pendragon I hope this gets you to learn more about it, and ideally play it at some point.

Just in case you are new to Pendragon, I should start with a little detail about the game itself. Pendragon appeared in 1985, in one of Chaosium’s gorgeous boxed sets. The cover by Jodie Lee and interior illustrations by Lisa A Free are among some of the best RPG artwork of the time, and one of the things that initially attracted me to the game. Since its creation, Pendragon has passed through five editions and three different companies, but has remained largely unchanged. The main exception being the 4th edition, which adds a magic system that is potentially usable by player characters.

In Pendragon, your characters are all knights in the era of King Arthur. However, by the era of Arthur we don’t just mean the time he was king. Pendragon comes with a vast and detailed timeline that takes characters from the time before Arthur, through his reign and finally to the tragic fall of his kingdom. Obviously, if your characters are experienced knights by the time the boy-king takes the throne, they’ll be pretty frail and old by the time Mordred leads his army against an aging Arthur. So as characters age they retire, handing the title of player character on to their sons and daughters. When player characters get old and retire, they can leave their land and even some of their reputation to their eldest heir to continue and advance their dynasty. As the campaign progresses, the player characters become richer and more powerful, perhaps even advancing to the Round Table.

Given the character potential of the Middle Ages, a game where you only play knights might seem rather limiting. However, what this allows Pendragon to do is focus on one particular type of character and tailor each adventure specifically for them. While you are a little stuffed if playing a knight doesn’t appeal, there are options for playing ladies and sorcerers, and even female knights (which may be ‘historically inaccurate’, but it’s all based on a myth anyway). However, there is plenty for each knight to do and plenty of variety to create different characters with different strengths.

Pendragon is often (and rightly) lauded for its generational legacy campaign, and its attention to detail in the setting and the myth. The rulebook divides the Arthurian cycle into different phases, and the later supplement ‘the Pendragon Campaign' breaks it down to a year by year guide for all manner of adventure. This alone makes Pendragon quite a unique and well crafted game, making it possible to miss just how good the rules system that underpins everything is.

So, what’s so good about the system? For a start, it is a simple system that doesn’t complicate as situations get more involved. Many simple systems end up adding all manner of bonuses and exceptions to cope with complex actions, but Pendragon manages to avoid that. To make a skill roll you roll 1D20 and have to roll less than your skill level. Roll your actual skill level and you have made a critical. A 20 is a fumble, so when you hit a skill of 20 you can’t fumble anymore. When you are in a contest, such as a swordfight, you need to roll under your skill, but higher than your opponent. Statistics (Strength, Dexterity, etc) make little difference to skills, so everything is encoded in one simple roll, although you might allow the odd bonus or penalty if you like.

Combat is extremely elegant, and not much more involved than a simple opposed roll. You decide who you are fighting and both of you roll your weapon skills. The highest result wins, as long as it is a successful roll and that character gets to damage their opponent (the loser doesn’t). This means you resolve two character’s actions in one roll and do away with any need for initiative, defense pools and actions.

Fighting multiple opponents? Then you have to divide your skill between them, but as evenly or unevenly as you like. So if you have a skill of 16 you might decide to have an effective skill of 8 against each of your two opponents. But you could instead focus on one, applying a skill of 12 against them and leaving only a skill of 4 against the other. Once more, simple, effective and smooth, the system allows players a certain degree of tactics when outnumbered, and ensures large groups of weak bandits can still be a problem for even an experienced group of knights.

In another nice twist, if you don’t beat your opponent (and get to do damage) but still made your roll, you managed to bring your shield into play to gain its armor rating against the damage you are taking. Damage is particularly interesting, as it is not defined by the weapon but the character. Each knight has a damage rating and the weapon they use only modifies that (with a standard sword being the average unmodified roll).

While combat and the basic system is impressive, another unique factor in the game are personality traits. Each character has a collection of 13 positive traits (Chastity, Valor, Honesty etc) and their opposites (Lust, Cowardice, Deceit etc) all rated like skills. The Gamemaster might call for a character to make a roll using one of their traits at any time, such as rolling gluttony to see if they overindulge at a feast. Fail, and they fall to their vice, succeed and the player can decide what the character does.

This might seem like roll playing rather than role playing, but the opposite is true. Many players refuse to let their characters fall to their darker urges, or do things that might embarrass their character. They won’t want to run from a battle and will insist they resist the wiles of a beautiful witch, just because they don’t want their character to fail. But in reality, not everyone is a brave and honest as they would like to be. Even the bravest knights have moments of cowardice, and the most virtuous fall to their vices on occasion. By forcing a personality roll, knights must prove themselves worthy or fail to do so. So if you don’t want your character to be a coward (for instance) you need to put more points in valor. As traits can be improved just like skills, your character can literally learn to be a better person as the game goes on.

However, this doesn’t mean the character is OK with their failings. Often, falling to a vice is what generates role play as the character realizes what they have done and feels a need to atone. For instance, the characters decide to go out for the night, insisting they are only going to have one or two drinks. Then, failing their trait rolls, they get horribly drunk and wake the next morning with a hangover and a feeling of shame for all the things they barely remember doing that night. When the players complain that ‘they said they weren’t going to get drunk’ the Gamemaster replies ‘you said you weren’t intending to, but that’s not what happened’. Just like real life. Given that many of Malory’s Arthurian tales involve knights falling to their desires and having adventures to restore their honor and virtue, it fits the setting perfectly.

While statistics (Strength, Dexterity etc) don’t count towards skills, they still serve a purpose. Statistics are used to calculate the knight’s base damage roll, hit points, how big a wound needs to be to count as a major wound and when they might fall unconscious etc. While statistics are important, the values don’t make a lot of difference unless they are especially high or low. This is an advantage, as when characters get old their statistics begin to drop, slowly but surely. Eventually this is what forces them to retire, despite their expert skills, as their damage and hit points quietly go down until they just aren’t fit enough to carry on adventuring.

I could go on for longer about the simple elegance of the Pendragon system, but I should let you discover the rest for yourself. In my game we constantly think of situations we expect the system to have a problem coping with. But time and again it proves us wrong, no matter how obscure what we are trying to do is. John Wick once coined ‘Stafford’s Law’ that states “If you think you have just had an amazing idea for an RPG system, chances are Greg Stafford thought of it first”. Nowhere is this more evident than in Pendragon.