Gamebooks provide a branching-path framework for a single player to determine their fate, with more advanced gamebooks using dice to resolve conflicts. But what happens when the choices you make in a game are determining not just what but how the adventure takes place?

The Visible Guardrails of Gamebooks

Gamebooks have been around for quite some time, with Flying Buffalo laying claim to having invented one of the first--not surprisingly, as a solo adventure for Tunnels & Trolls. As a single-player experience, these types of gamebooks provide a limited form of agency, allowing the player some freedom of choice while at the same time creating a unique experience each time that choice diverges.

The replayability of gamebooks depends on the number of branching paths, which provide different outcomes with each choice. Combat with dice adds another variable; a player may be able to defeat a monster on one play through but not on another due to the randomness of dice rolls.

All this is transparent to the player; the reader can see what pages to flip to and after the first play-through, knows the outcome of those decisions. In fantasy gamebooks, this mimics dungeon exploration in Dungeons & Dragons, where a dungeon tends to be static to the extent the players map it out, but is largely unknown until it is explored. Sandbox campaigns don't fill out the dungeon (or other terrain) until the game takes place, which means the game master doesn't necessarily know what's coming next either.

Similarly, a gamebook provides invisible guardrails--but the guardrails are still there, visible to anyone who flips ahead to the book or reads choices out of order. Depending on your perspective, this can make a gamebook exciting or rote. And some of that experience is likely shaped by the genre.

Horror vs. Fantasy

Heroic fantasy games as established by D&D tend to be about power. Chainmail had "hero" and "superhero" as titles for adventurers, titles which carried over to the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons fighter class. This escalation of power through levels and advancement can clash with gamebook play, which limits player agency to a few choices.

Conversely, horror games are about taking that power away. Call of Cthulhu's infamous sanity mechanic ensures that even if characters acquire more firepower, they will eventually succumb, which in turn reinforces the horror aspect.

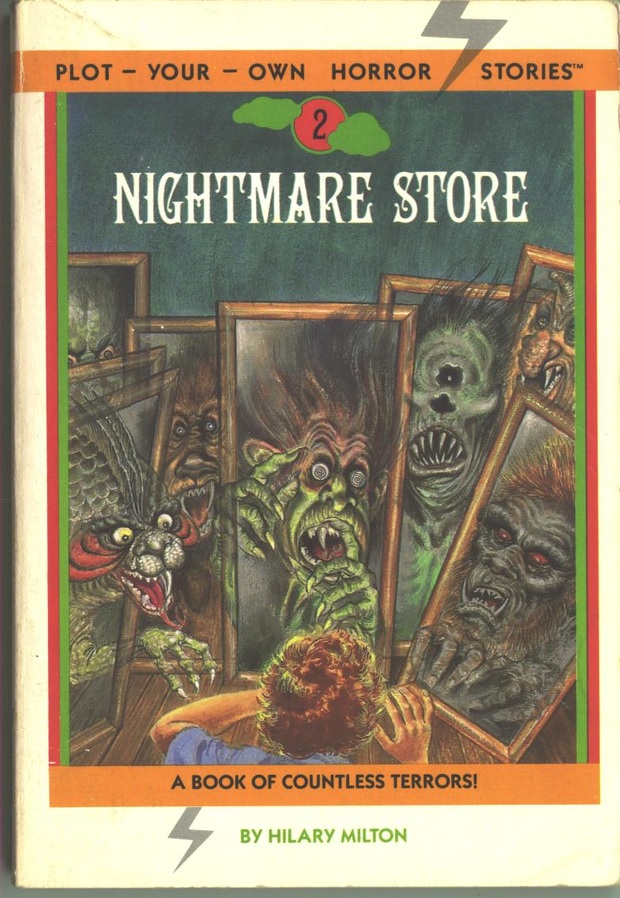

Horror gamebooks fill an interesting niche, turning the limited player agency into a storytelling advantage: the player's choices are limited because they are struggling to not succumb to some horrible event. For an example of how this plays out, the "Plot-Your-Own-Horror-Story", Nightmare Store, provides a classic example.

Nightmare Store

I came across Nightmare Store as a kid in school and was shocked by how frightening the book could be. The protagonist falls asleep in a mall and wakes up at night, locked in, as everything in the mall comes to life and attempts to take yours. Nightmare Store isn't about surviving so much as experiencing the horror; obvious attempts to escape can end in death, attacking monsters head on can mean surviving a little longer. What's unique about this series is that, as Demian's Gamebook Web Page explains, "quite a few choices determine not what the reader's character does, but rather what will happen next; for example, rather than asking whether or not to open a door, a choice may ask what will be behind it!"

Nightmare Store gives the player the opportunity not just to play along, hoping their choices allow the protagonist to escape; it lets the player determine their fate, becoming their own game master. This is a significant divergence from a "gain power" sort of play. Instead, the player is asked to join in on the horror by crafting their own scary story. It's not for everybody.

Why This Isn't for Everybody

Player agency is a tricky thing, determined as much by actual agency as the player's knowledge and awareness of their agency. It pivots on a player seeing dice rolls and game masters fudging rolls (or not), in the spirit of telling a good story.

There's a fine line between asking someone how they feel and telling them, or letting players determine their reaction vs. railroading them. If this effort is too overt, players get annoyed. It's the same reaction we have to headlines like "This buffalo just wanted to buy a pair of shoes. What happened next will blow your mind" -- the headline is providing an intentional inconsistency (which is psychologically distressing) and then telling us how to feel about it.

How this series of gamebooks work is an insight to differing styles of play. When players are interested in winning, it's easy to invest in striving for the best outcome (surviving, in the case of a horror gamebook). When players are more interested in telling an interesting horror story, player choice becomes much less important. As Guillermo explains in his review of another gamebook in the series, Craven House Horrors:

This lack of player choice, and my ability to only influence the narrative but not the outcome, is likely why I found this gamebook so frightening as a kid. Take a look and see for yourself.

The Visible Guardrails of Gamebooks

Gamebooks have been around for quite some time, with Flying Buffalo laying claim to having invented one of the first--not surprisingly, as a solo adventure for Tunnels & Trolls. As a single-player experience, these types of gamebooks provide a limited form of agency, allowing the player some freedom of choice while at the same time creating a unique experience each time that choice diverges.

The replayability of gamebooks depends on the number of branching paths, which provide different outcomes with each choice. Combat with dice adds another variable; a player may be able to defeat a monster on one play through but not on another due to the randomness of dice rolls.

All this is transparent to the player; the reader can see what pages to flip to and after the first play-through, knows the outcome of those decisions. In fantasy gamebooks, this mimics dungeon exploration in Dungeons & Dragons, where a dungeon tends to be static to the extent the players map it out, but is largely unknown until it is explored. Sandbox campaigns don't fill out the dungeon (or other terrain) until the game takes place, which means the game master doesn't necessarily know what's coming next either.

Similarly, a gamebook provides invisible guardrails--but the guardrails are still there, visible to anyone who flips ahead to the book or reads choices out of order. Depending on your perspective, this can make a gamebook exciting or rote. And some of that experience is likely shaped by the genre.

Horror vs. Fantasy

Heroic fantasy games as established by D&D tend to be about power. Chainmail had "hero" and "superhero" as titles for adventurers, titles which carried over to the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons fighter class. This escalation of power through levels and advancement can clash with gamebook play, which limits player agency to a few choices.

Conversely, horror games are about taking that power away. Call of Cthulhu's infamous sanity mechanic ensures that even if characters acquire more firepower, they will eventually succumb, which in turn reinforces the horror aspect.

Horror gamebooks fill an interesting niche, turning the limited player agency into a storytelling advantage: the player's choices are limited because they are struggling to not succumb to some horrible event. For an example of how this plays out, the "Plot-Your-Own-Horror-Story", Nightmare Store, provides a classic example.

Nightmare Store

I came across Nightmare Store as a kid in school and was shocked by how frightening the book could be. The protagonist falls asleep in a mall and wakes up at night, locked in, as everything in the mall comes to life and attempts to take yours. Nightmare Store isn't about surviving so much as experiencing the horror; obvious attempts to escape can end in death, attacking monsters head on can mean surviving a little longer. What's unique about this series is that, as Demian's Gamebook Web Page explains, "quite a few choices determine not what the reader's character does, but rather what will happen next; for example, rather than asking whether or not to open a door, a choice may ask what will be behind it!"

Nightmare Store gives the player the opportunity not just to play along, hoping their choices allow the protagonist to escape; it lets the player determine their fate, becoming their own game master. This is a significant divergence from a "gain power" sort of play. Instead, the player is asked to join in on the horror by crafting their own scary story. It's not for everybody.

Why This Isn't for Everybody

Player agency is a tricky thing, determined as much by actual agency as the player's knowledge and awareness of their agency. It pivots on a player seeing dice rolls and game masters fudging rolls (or not), in the spirit of telling a good story.

There's a fine line between asking someone how they feel and telling them, or letting players determine their reaction vs. railroading them. If this effort is too overt, players get annoyed. It's the same reaction we have to headlines like "This buffalo just wanted to buy a pair of shoes. What happened next will blow your mind" -- the headline is providing an intentional inconsistency (which is psychologically distressing) and then telling us how to feel about it.

How this series of gamebooks work is an insight to differing styles of play. When players are interested in winning, it's easy to invest in striving for the best outcome (surviving, in the case of a horror gamebook). When players are more interested in telling an interesting horror story, player choice becomes much less important. As Guillermo explains in his review of another gamebook in the series, Craven House Horrors:

This unusual form of gameplay has elicited complaints, but I think it works very well, since the way the book is set up, it seems as if the author is engaging with the player in dialogue and responding to his thoughts (the responses having often-unexpected consequences). This creates a psychological bond between the reader and the story that also serves to create a feeling of helplessness, which is quite appropriate for a horror book.

This lack of player choice, and my ability to only influence the narrative but not the outcome, is likely why I found this gamebook so frightening as a kid. Take a look and see for yourself.