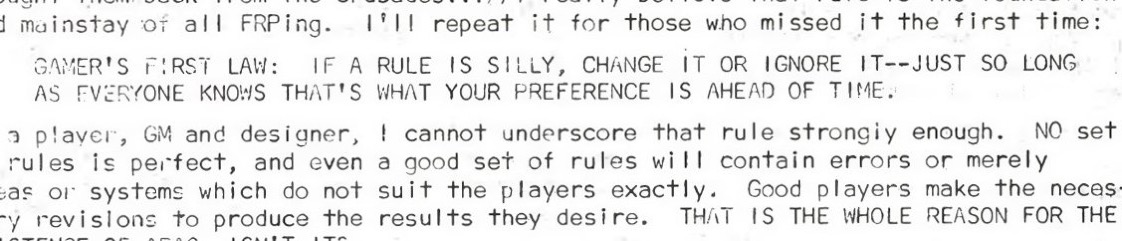

Jon Peterson discusses the origins of Rule Zero on his blog. It featured as early as 1978 in Alarums & Excursions #38.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Origins of ‘Rule Zero’

- Thread starter Morrus

- Start date

Jon Peterson discusses the origins of Rule Zero on his blog. It featured as early as 1978 in Alarums & Excursions #38.

Morrus is the owner of EN World and EN Publishing, creator of the ENnies, creator of the What's OLD is NEW (WOIN), Simply6, and Awfully Cheerful Engine game systems, publisher of Level Up: Advanced 5th Edition, and co-host of the weekly Morrus' Unofficial Tabletop RPG Talk podcast. He has been a game publisher and RPG community administrator for over 20 years, and has been reporting on TTRPG and D&D news for over two decades.

Secondly, it’s a truism to say simplified, generic rules that can be applied in any circumstance don’t require a rule zero. If nothing is specific then nothing will come into conflict. That kind of approach doesn’t work with D&D.

I agree with this statement, but I'd expand it to include what @Lanefan was saying.

Systems that are more generic (abstract) or rely on frameworks and guidelines (as opposed to "rules") don't rely on a "Rule 0" because the concept of a Rule 0 is baked into the system. "Rule 0" is the social adjudication (by the GM, by the players, or by both) of issues that arise from applying the framework and guidelines to particular situations.

I think of this as the common sense conundrum. To use the two lance example provided above-

Some systems (like D&D or even more rules-heavy systems) would adjudicate this by examining specific rules with regard to initiative, and dual-wielding, and possibly even more specific rules regarding use of two lances while mounted.

Other systems would just have the DM and player make determinations (as illustrated by loverdrive) as to what effects this would have with generic game terms (soft move, hard move, golden opportunity) and explain this in terms of the fiction.

Here's the thing, though; have you read many threads on enworld? Maybe one involving the divide between crunch and lore? Or players asking about the way a rule is phrased? Possibly the effect of a silence spell on bats? Or, heck, players who want their druids to wear metal armor and are worried they might explode? Maybe someone wondering about swimming in plate?

What you run into is the common sense conundrum. People don't always agree on what constitutes "common sense." That's why more codified rule systems tend to have an advantage for some types of tables - disputes can be handled through an objective rule.

On the other hand, abstract rules or ones that rely on guidelines require that there is significant table buy-in and avoidance of the common sense conundrum.

To use the example above, as absurd as it might seem, the GM and the players are in general agreement about the effect of dual-wielding lances on horseback (it would be bad). In a rules-heavy game, this would be explicit and known within the rules. In a guidelines game, however, this would be up to the instant social adjudication; arguably, it is resolved easily (the GM is not preventing the player), but it still requires that the table is in general agreement that, for example, the GM should burden the player in any way for that choice. It might seem like common sense, but people often disagree on that.

In short, the common sense conundrum (as I refer to it) tends to lurk at the edge of these debates; there needs to be significant table buy-in about the shared fiction and the effects that does not need to refer to an agreed-upon referent for guidelines and frameworks to work.

I this is partially because everyone has horror stories about abusive DMs. Rule 0 is just one of many things these DMs have used improperly, so I think it all gets wrapped in the same package. With players, the only thing the DM has to stop abuse by players is Rule 0 (at least without being abusive themselves), so that's how it's remembered.The only real problem I have with Rule 0 is when it is used abusively--because a lot of people talk about players using all the other game rules abusively, and pretty much never talk about DMs using Rule 0 abusively.

Thomas Shey

Legend

Not sure if I entirely agree with that. That's probably closer to the truth for the straight-up OSR retro clones, and a number of OSR games also include Rule Zero, but I'm not sure about some of the others. There is certainly a "DIY approach" that is part of the culture, but I don't think that we should conflate Rule Zero with an openness to kitbash the game. Fate, for example, does not have Rule Zero, but it also encourages people to tinker with the game and make the game their own.

There's some overlap, but as noted "Willing to do house rules to patch holes and/or serve a particular purpose" and "Thinks its a virtue to ignore whats already there any time he doesn't like it" are not actually identical sets.

I also recall reading that the only time that Pathfinder surpassed D&D 4E was when WotC basically dropped support of 4E and stopped publishing for it as it began in-house development of D&D Next. 4E may be regarded as D&D's "New Coke," but New Coke still outsold more than Pepsi, which did its best to capitalize on the backlash against New Coke. And brand loyalty to Coke resulted in grassroots organizing to bring back "Old Coke."

Yup. Personally, even though it didn't work for me I respect the 4e design more than the 5e design, but its hard not to see the latter as responsive to demand.

Last edited:

Thomas Shey

Legend

I this is partially because everyone has horror stories about abusive DMs. Rule 0 is just one of many things these DMs have used improperly, so I think it all gets wrapped in the same package. With players, the only thing the DM has to stop abuse by players is Rule 0 (at least without being abusive themselves), so that's how it's remembered.

At the very least, Rule 0 is perfectly capable of empowering problems in terms of who has control over the rule-system part of the game heavily into GM hands; he could try and do it anyway, and possibly get away with it just because of the intrinsic power imbalance, but there's distinctly a different dynamic to being able to point to the rules saying its okay for him to do this, and just demanding it.

loverdrive

your favorite gm's favorite gm (She/Her)

Well, the GM needs to make a soft move first and only then they can hit the bastard where it hurts. As of how it works, see below.I meant on the same footing at the table: that everyone there is operating on the same basis as to how this two-lance business is likely to go.

I'm talking about guidelines on, well, invoking rule zero, if we count making judgement calls as such (though I disagree with it, but that's beside the point).You quite correctly used the word 'guidelines' two or three times in your post; and it's that they're guidelines rather than rules which in part makes Rule 0 necessary: it's Rule 0 that turns guidelines in the books to rulings (and thus rules) at each individual table.

D&Desque rule zero boils down to "figure it out", and in newer editions (well, since AD&D 2E at least, lol) presumes undoing existing rules and replacing them, instead of filling the blanks.

Compare it with PbtA games, where the GM has Agenda, Principles and Moves, which provide solid framework for making good judgement calls. I'm gonna use Dungeon World as an example, since it's in the same genre as D&D, and also kinda cosplays it.

In Dungeon World, the GM has agenda:

- Portray a fantastic world

- Fill the characters’ lives with adventure

- Play to find out what happens

- Draw maps, leave blanks

- Address the characters, not the players

- Embrace the fantastic

- Make a move that follows

- Never speak the name of your move

- Give every monster life

- Name every person

- Ask questions and use the answers

- Be a fan of the characters

- Think dangerous

- Begin and end with the fiction

- Think offscreen, too

Agenda and principles vary from game to game, as the specific genre demands. So, in Monsterhearts, principles look like this:

- Embrace melodrama.

- Address yourself to the characters, not the players.

- Make monsters seem human, and vice versa.

- Make labels matter.

- Give everyone a messy life.

- Find the catch.

- Ask provocative questions and build on the answers.

- Be a fan of the main characters.

- Treat side characters like stolen cars.

- Give side characters simple, divisive motivations.

- Sometimes, disclaim decision making.

Also, there're GM moves, which are ready to use prompts. I'm not gonna list all of them, as this post is already full of lists, but I'll give a couple of examples (again, from Dungeon World):

- Show signs of an approaching threat: This is one of your most versatile moves. “Threat” means anything bad that’s on the way. With this move, you just show them that something’s going to happen unless they do something about it.

- Separate Them: There are few things worse than being in the middle of a raging battle with blood-thirsty owlbears on all sides—one of those things is being in the middle of that battle with no one at your back. Separating the characters can mean anything from being pushed apart in the heat of battle to being teleported to the far end of the dungeon. Whatever way it occurs, it’s bound to cause problems.

- Put someone in a spot: A spot is someplace where a character needs to make tough choices. Put them, or something they care about, in the path of destruction. The harder the choice, the tougher the spot.

- Tell them the requirements or consequences and ask: This move is particularly good when they want something that’s not covered by a move, or they’ve failed a move. They can do it, sure, but they’ll have to pay the price. Or, they can do it, but there will be consequences. Maybe they can swim through the shark-infested moat before being devoured, but they’ll need a distraction. Of course, this is made clear to the characters, not just the players: the sharks are in a starved frenzy, for example.

Soft moves (those that aren't bad, or don't have longterm consequences, or give a moment to react) can be made whenever you feel like it. But hard moves can only be made when a player rolls a miss or when they ignore a soft move for whatever reason (probably because they've decided to address another threat).

So, they can't just say to a two-lanced knight that he got himself killed without a proper warning. No, they need to establish the fact that it's gonna be very risky, and only then they get to make a hard move -- they have to give the character (and the player) time to react.

And it applies to all situations, not only to theoretical Ronald the Madman. When a dragon unleashes its stone-melting fire breath, in D&D the DM asks for save vs. breath (or Reflex save, or Dex save, doesn't matter), but in Dungeon World the GM says "The beast inhales air into its massive lungs and its about to turn you into a well done steak. What ya gonna do?".

Yeah, both in D&D and in DW a wizard can say "I'm gonna teleport away with my magic!", but in D&D you need to break the rules to allow it. In DW it's a normal, natural action, just like dodging out of the harms way.

loverdrive

your favorite gm's favorite gm (She/Her)

I'd say if there's no agreement on shared fiction, then it's either can be fixed with a brief clarification, or these people shouldn't play this particular game together — some people don't "get" some genres, and that's okay.I agree with this statement, but I'd expand it to include what @Lanefan was saying.

Systems that are more generic (abstract) or rely on frameworks and guidelines (as opposed to "rules") don't rely on a "Rule 0" because the concept of a Rule 0 is baked into the system. "Rule 0" is the social adjudication (by the GM, by the players, or by both) of issues that arise from applying the framework and guidelines to particular situations.

I think of this as the common sense conundrum. To use the two lance example provided above-

Some systems (like D&D or even more rules-heavy systems) would adjudicate this by examining specific rules with regard to initiative, and dual-wielding, and possibly even more specific rules regarding use of two lances while mounted.

Other systems would just have the DM and player make determinations (as illustrated by loverdrive) as to what effects this would have with generic game terms (soft move, hard move, golden opportunity) and explain this in terms of the fiction.

Here's the thing, though; have you read many threads on enworld? Maybe one involving the divide between crunch and lore? Or players asking about the way a rule is phrased? Possibly the effect of a silence spell on bats? Or, heck, players who want their druids to wear metal armor and are worried they might explode? Maybe someone wondering about swimming in plate?

What you run into is the common sense conundrum. People don't always agree on what constitutes "common sense." That's why more codified rule systems tend to have an advantage for some types of tables - disputes can be handled through an objective rule.

On the other hand, abstract rules or ones that rely on guidelines require that there is significant table buy-in and avoidance of the common sense conundrum.

To use the example above, as absurd as it might seem, the GM and the players are in general agreement about the effect of dual-wielding lances on horseback (it would be bad). In a rules-heavy game, this would be explicit and known within the rules. In a guidelines game, however, this would be up to the instant social adjudication; arguably, it is resolved easily (the GM is not preventing the player), but it still requires that the table is in general agreement that, for example, the GM should burden the player in any way for that choice. It might seem like common sense, but people often disagree on that.

In short, the common sense conundrum (as I refer to it) tends to lurk at the edge of these debates; there needs to be significant table buy-in about the shared fiction and the effects that does not need to refer to an agreed-upon referent for guidelines and frameworks to work.

Also, it may be obvious, but what makes sense and what doesn't largely depends on the genre, the tone and the previous events.

A gallant knight on a mighty steed, wielding a shiny shield and master-crafted sword would make sense in a LotResque game, but but very little sense (at least, if played straight) in Monty Python and the Holy Grail — so someone who really wants to play a gallant knight shouldn't be at the table where a game about the Order of Silly Martial Arts is played, and a rule, no matter how objective and well-worded that requires everyone to practice ridiculous martial art isn't going to make them accept the shared fiction. At best it's going to be like "ugh, okay, I guess" sigh.

I'd say if there's no agreement on shared fiction, then it's either can be fixed with a brief clarification, or these people shouldn't play this particular game together — some people don't "get" some genres, and that's okay.

Also, it may be obvious, but what makes sense and what doesn't largely depends on the genre, the tone and the previous events.

A gallant knight on a mighty steed, wielding a shiny shield and master-crafted sword would make sense in a LotResque game, but but very little sense (at least, if played straight) in Monty Python and the Holy Grail — so someone who really wants to play a gallant knight shouldn't be at the table where a game about the Order of Silly Martial Arts is played, and a rule, no matter how objective and well-worded that requires everyone to practice ridiculous martial art isn't going to make them accept the shared fiction. At best it's going to be like "ugh, okay, I guess" sigh.

All you are doing is re-stating the obvious- if everyone agrees, it's going to work out. Which is the whole issue behind the common sense conundrum.

To you, the idea that something does, or doesn't, happen in a shared fiction due to it being a particular genre ... well, if someone doesn't agree with you, then they don't "get" it. Because it's common sense! Of course, it is equally plausible that the other person thinks that you are the one that doesn't "get" it.

And that's the point. A more rules-heavy game (like a D&D) tends to have more of these disputes handled by RAW. That is the external referent. A game that relies more on guidelines and frameworks is going to depend on the buy-in of the GM and the players and on the agreement on shared fiction.

Which is to say that the "Rule 0" (the discretionary part) is actually happening on an ongoing and negotiated basis, with the negotiation either implicit (the GM and players modeling their actions on what they think is acceptable for the group shared fiction) or explicit (conversations and clarifications to determine how to resolve a dispute between different people as to what the shared fiction would entail).

loverdrive

your favorite gm's favorite gm (She/Her)

And then... We shouldn't play together.To you, the idea that something does, or doesn't, happen in a shared fiction due to it being a particular genre ... well, if someone doesn't agree with you, then they don't "get" it. Because it's common sense! Of course, it is equally plausible that the other person thinks that you are the one that doesn't "get" it.

I don't think rules being objective does any good in preventing such issues, because such issues kinda transcend dice and hit points.

If someone wants to see hopelessness of Dark Souls, and someone else wants heroic feats of Dragonlance, then it doesn't matter that characters objectively cast through spell slots or objectively survive a 60ft. fall — they ain't gonna mesh well together.

But that's besides the point. Even D&D could benefit from a solid framework for invoking rule 0, like:

- Try to reskin existing stuff first

- Don't hand Advantages on attacks easily

- Prefer Advantages and Disadvantages over bonusi and penalties

- Keep Bounded Accuracy in mind

- Don't allow things that are core abilities of other classes/subclasses

For me, almost every instance of adding rule 0 feels like they've built a system like a boardgame, where rules are supposed to always work, then remembered that it's not a plain boardgame and added a footnote "ok, figure it yourselves" instead of accounting for the fact that TTRPGs have a fiction component and rigid rules aren't gonna work all the time, instead of providing a generalized solution that you can fall back on.

Well, they kinda did, but their generalized solution is "figure it out", which isn't super helpful.

Last edited:

Maxperson

Morkus from Orkus

This. Every time I see the fiction first rules describe, they have described a game that lives entirely within Rule 0.And that's the point. A more rules-heavy game (like a D&D) tends to have more of these disputes handled by RAW. That is the external referent. A game that relies more on guidelines and frameworks is going to depend on the buy-in of the GM and the players and on the agreement on shared fiction.

Which is to say that the "Rule 0" (the discretionary part) is actually happening on an ongoing and negotiated basis, with the negotiation either implicit (the GM and players modeling their actions on what they think is acceptable for the group shared fiction) or explicit (conversations and clarifications to determine how to resolve a dispute between different people as to what the shared fiction would entail).

In a rules first game, Rule 0 exists solely to make the game better when the DM sees the need to change something, whether that's a bad rule, a hole, or just something that the game hasn't made a rule for and he feels needs a rule.

Whereas in a fiction first game, the fiction informs the DM about what to do, within a much lighter framework of actual rules. This means that the DM is enacting Rule 0 everytime he comes up with a response based on the fiction and has the players roll or suffer some success/mishap.

Rule 0 has grown so large in fiction first games, that the players aren't seeing the forest for the trees.

Last edited:

Maxperson

Morkus from Orkus

That seems like good advice. Personally, I reskin on some occasions and create from scratch on others, but I've been doing this for a very long time, so I've made most of my large mistaked decades ago.that's besides the point. Even D&D could benefit from a solid framework for invoking rule 0, like:

- Try to reskin existing stuff first

Good advice.

- Don't hand Advantages on attacks easily

This I don't agree with. Advantage/Disadvantage gives a greater bonus/penalty on most occasions than a bonus or penalty does usually does. Sometimes it's better to give Advantage/Disadvantage and other times it's better to give a bonus/penalty. The rules should talk about the cough advantages and disadvantages of both methods.

- Prefer Advantages and Disadvantages over bonusi and penalties

Wise advice.

- Keep Bounded Accuracy in mind

And again something I don't agree with. You should be careful if/when you hand out core abilities, but they can and do sometimes make sense to give out. Especially when there isn't a player at the table with the particular class/subclass core ability in question.

- Don't allow things that are core abilities of other classes/subclasses

This doesn't exist. Even in 3e, the rigidiest of D&D editions, rules often failed to cover a situation due to a hole in the rule, were vague, or just didn't make sense to apply to a particular situation. Then there were also times where an addition of a rule, subtraction of a rule or blanket alteration of a rule would improve the game for the group.Even the rigidiest of rigidiest rules have meta-rules, that determine how, when and why they should be used.

Rule 0 exists to make the game better. It may not have started out that way, but that's the way it has been since 1e.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 89

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 301

- Views

- 25K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 12K

Recent & Upcoming Releases

-

June 18 2026 -

October 1 2026

Related Articles

-

First Encounter | A rules-lite fantasy RPG with zero prep

- Started by tabletopjess

- Replies: 1

-

-

-

-

Recent & Upcoming Releases

-

June 18 2026 -

October 1 2026