clearstream

(He, Him)

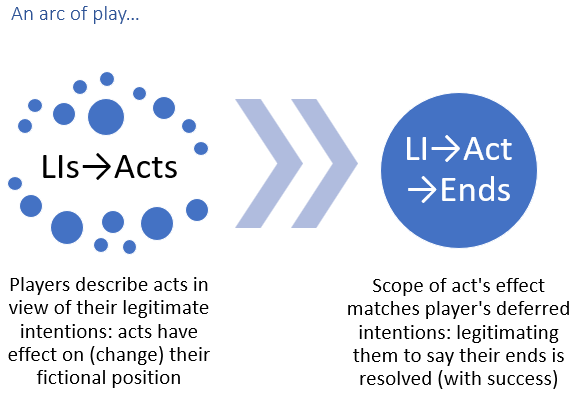

I've been mulling over a principle I use that enables a series of acts over an arc of play to successively revise fictional position, until it's legitimate to include the resolution of a conflict or larger goal in what we say next. Essentially, players draft legitimate intentions, describe acts and check the arrow of momentum (system | fiction), and then redraft legitimate intentions, so that it always and eventually best follows that what they describe doing matches what they intend to resolve. The principle is used to achieve something that rules can also be designed to achieve, such as the Skill Challenge rules in 4e. In this post, I don't aim to argue for one or another, but only lay out the concept to see if others find it workable for them?

I should add as background that I take RPG to involve ongoing authorship of a common fiction, through a continuous process of drafting and revising, that all participate in, with linkage between system and fiction. Momentum flows through that linkage. Everyone continually aims to say what best follows from their position (their fictional position, most importantly.) I won't dive into the full background on this, but fictional position is a powerful concept proposed by Vincent Baker and preserved on his old "anyway" site.

When I say principles, I don't mean rules, guidelines or preferences. I mean principles in the narrow sense of what I ought to do to have the play I'm aiming for. I don't mean that you ought to prefer that play, which is a wider kind of principle that feels a bit like a preference. Preferences don't matter to this discussion: only whether the envisioned principle if grasped and upheld could for others have the result described above. It might be that in my implementation I'm also doing something unnoted, so I'd like to understand that.

One way to spot a legitimate intention is that the result of an action that player describes looks extremely likely to match that intention. Prescriptively, when the scope of an act’s effect matches a legitimate intention then its consequences include that which is intended. And while the consequences of success are constrained to what is legitimate based on what has been said to be true, it is legitimate to accept uncertainty. Players can guess at truths off-camera and success legitimately include validating their prediction. In that case, success = successfully validating or falsifying the prediction.

Legitimate intentions drive arcs of play, in which a series of acts successively update fictional position until players can describe an act whose consequences include resolving their goal or conflict. An example might be an act where I research vorpal blades. That sets me up down the line to break open the Azure Vault of Perfidious Petra with the legitimate intention of finding a vorpal blade there. (With probably a bunch of other acts needed in between, to update my fictional position until I can legitimately say that.) I can of course break open any number of vaults intending to find a vorpal blade, but the only legitimate intention I can form about that is the one discussed above, which amounts to an intent to learn if there is a vorpal blade within. Success = learning that (whether true or false.)

This is roughly what results (each dot is an act)

I should add as background that I take RPG to involve ongoing authorship of a common fiction, through a continuous process of drafting and revising, that all participate in, with linkage between system and fiction. Momentum flows through that linkage. Everyone continually aims to say what best follows from their position (their fictional position, most importantly.) I won't dive into the full background on this, but fictional position is a powerful concept proposed by Vincent Baker and preserved on his old "anyway" site.

When I say principles, I don't mean rules, guidelines or preferences. I mean principles in the narrow sense of what I ought to do to have the play I'm aiming for. I don't mean that you ought to prefer that play, which is a wider kind of principle that feels a bit like a preference. Preferences don't matter to this discussion: only whether the envisioned principle if grasped and upheld could for others have the result described above. It might be that in my implementation I'm also doing something unnoted, so I'd like to understand that.

Legitimate Intentions

So what are legitimate intentions? In short, the principle of saying what follows from fictional position is applied to player intentions. For example, intending to find a specific object inside a chest is only legitimate if it would best follow to say that object is there. This is easy to see if as a player I pick a random chest, say the one at the foot of my bed in the inn I'm staying at, and say "I search the chest for a vorpal blade." I tell the GM that my intention is to find the vorpal blade." That's usually not legitimate because it usually doesn't best follow that there's a vorpal blade in that chest without some other truths having been established to make it legitimate (such as that I stowed my vorpal blade in that chest last night.) In such a situation, a legitimate intention could be “I want to learn what is inside the chest.” Success at opening the chest = success at satisfying my legitimate intention (l learned what was inside the chest.)One way to spot a legitimate intention is that the result of an action that player describes looks extremely likely to match that intention. Prescriptively, when the scope of an act’s effect matches a legitimate intention then its consequences include that which is intended. And while the consequences of success are constrained to what is legitimate based on what has been said to be true, it is legitimate to accept uncertainty. Players can guess at truths off-camera and success legitimately include validating their prediction. In that case, success = successfully validating or falsifying the prediction.

Legitimate intentions drive arcs of play, in which a series of acts successively update fictional position until players can describe an act whose consequences include resolving their goal or conflict. An example might be an act where I research vorpal blades. That sets me up down the line to break open the Azure Vault of Perfidious Petra with the legitimate intention of finding a vorpal blade there. (With probably a bunch of other acts needed in between, to update my fictional position until I can legitimately say that.) I can of course break open any number of vaults intending to find a vorpal blade, but the only legitimate intention I can form about that is the one discussed above, which amounts to an intent to learn if there is a vorpal blade within. Success = learning that (whether true or false.)

No Hidden Gotchas

A related, and I think necessary principle is one I call no hidden gotchas. GM might at times establish truths that have not been shared with players yet. They ought to normally avoid hidden descriptions that would refute fiction that players have no reason to doubt. An example of this might be a clerk answering questions under a zone of truth spell. The clerk should not testify to veracity and certainty on matters that GM has established behind the scenes to be false. They could certainly establish imagined events that go against that, so this principle is saying that they ought not to. Where GM is the source of player knowledge of what is true about the world, they are in a unique position: the world seen through their words is something that they can make principled choices about.This is roughly what results (each dot is an act)