Pie For Everyone, Just Sliced Very Thinly: The Economics of RPG book Production

This article has been updated with a missing pie chart! Simon Rogers of Pelgrane Press has written an article for EN World which takes a detailed look at many of the costs of producing a roleplaying game product. He includes charts. "Last week Morrus provided a list of word rates paid by tabletop RPG publishers. He gleaned from public sources and in discussion with writers. The question arose – why are the rates low? This article centres on the economics of RPG book production and sales, but I’ll start with a preamble directed at writers and other RPG freelancers."

[h=4]Will You Get Your Pie?[/h]

When I mentioned Morrus’ list, one writer of my acquaintance said “a list of publishers who pay reliably would be a damn sight more useful.” While the word rates are fundamentally important, there’s a lot more for writers to consider when working with a publisher than the bare word rate.

[h=4]Should you Work for Very Little?[/h]

If you want to enter the modestly paid, astronaut-rare ranks of the full time RPG writer, what should you do? First, under no circumstances give up your day job until you command a sustainable word rate, that is words times word rate per day equals a living wage. To begin with, consider working for a lower rate, work hard and professionally and get a good reputation. Chase for money owed without the slightest guilt. Work for free on your own site, or spend your spare writing time creating pitches for publishers you like. Paizo in particular write amazing outlines for their writers.

Set yourself a time limit of, say, one year. If you are earning your target word rate by then, consider working full time. If you enjoy publishing, sales, fulfilment, handling customer queries, wrangling other creators,dealing with printers, marketing and website design, consider becoming a COP (creator-owned publisher) instead of a writer.

[h=4]A Slice of Pelgrane Pie[/h]

Now, in the interests of transparency, I’ll discuss Pelgrane Press’s RPG word rate as of the end of January 2015. Our writers on a fixed rate receive between 3c and 7c a word. As an exception we once paid Gary Gygax 10c for a short article on the Dying Earth.

In the past, I’ve taken the very easy option of employing a very few talented writers, asking them to write want they want, and paying them what they ask. We’ve supplemented these stalwarts with new writers because our in-house writers are tied up, because of the increasing number of books we produce, and that we want to work with a wider variety of voices.

A 3c-a-word writer is generally a first-time writer, or at least one who is inexperienced in the field, and such writers will always, always cost us more than a known 5c-a-word writer. We give those new writers time-consuming feedback, hone and polish their work more thoroughly, and take the risk that they will flake or one occasion plagiarise other sources. They require time and attention from our existing writers, who could otherwise be writing. So why do we do it? The answer is development. We are keen to develop new writers to work with us and other publishers – and that, for example, is how Gareth Hanrahan’s already solid writing talent was honed this way and it’s how Evil Hat’s Lenny Balsera got his first RPG writing gig (he tells me). If an enthusiastic writer with a professional attitude, who has done their homework offers us a solid pitch, there is every chance we will work with them to publish it.

[h=4]Expanding Pie[/h]

Aside from a fixed word rate, we have also, historically, offered net margin agreements to certain selected writers who were willing to accept the downside of such a deal. These are: a delay in revenue and the risk of a lower word rate delay in payment and it requires them to trust the publisher (us) not to exaggerate our costs. Where we’ve offered this deal, it’s been a choice between net margin and a word rate.

Net margin is, in principle, straightforward. The publisher adds up agreed fixed costs of production and then deducts those from the gross margin. Gross margin is the total of sales minus any per-unit costs.

The writer is then paid a percentage of this figure. In our case, that percentage to date has always been 50%.

Net margins deals have resulted in word rates of between 2c and 20c a word and the writers benefit from the long tail – the gradual continuing trickle of sales over many years.

I’m reluctant to enter into such deals now in part because of the time and tedium of calculating the royalties.

[h=4]Making the Pie[/h]

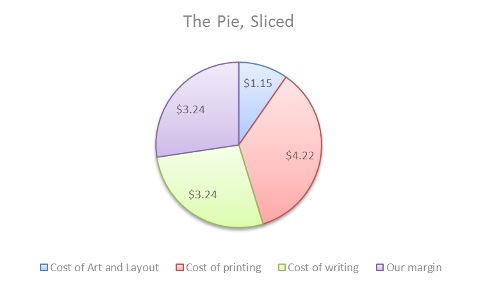

Net margin deals are tailor-made to illustrate how the production pie is sliced. I’ll use a low-end example to illustrate a simple case of production expenses and revenue for a product. The example I’ve chosen was published at a time that all work was invoiced by freelancers and was therefore easy to quantify. I never charge for my own time. It doesn’t include copy editing (which was haphazard – or I did it – which amounts to the same thing) and any unexpected expenses. The figures are accurate but I’ve adjusted dates and titles for the author’s modesty. Because this was for one of our settings, the writing was work for hire – that is we acquire the copyright. (Rights is perhaps worth another article in itself.)

Let me introduce Pitching Kittens from a Van, a thrilling supplement for the Satsuma RPG.

In 2010, an unknown writer approached me with a well written and solid adventure for the Satsuma RPG. The writer had already playtested his adventure three times, and asked if I’d be interested in publishing it. The writer said it wouldn’t be ready for at least six months for extensive and in-depth further playtesting. He exhibited a professional attitude, had done most of the work already, so I thought I’d offer him the choice between a word rate of 3c or the risk of 50% of net margin. The writer, someone who was not reliant on writing income, took the latter option.

Another six months later after rewriting external playtesting, and external playtesting, we had a book ready to be laid out.

Our fixed costs for this book were simply art and layout. Now they’d also include 0.5 to 1c a word of of copy editing and development.

We were charged $230 for art (a front cover, four quarter pages and a full page mono interior) and $100 layout (which used an existing layout template).

[h=4]Slicing the Pie[/h]

The book was 20000 words, give or take. The PDF version was $14.95, later, we added a print version at $19.95. This was in part to see if releasing a PDF then a print version would affect sales, contrary to our established view that if you release the print version first, you maximise your revenue.

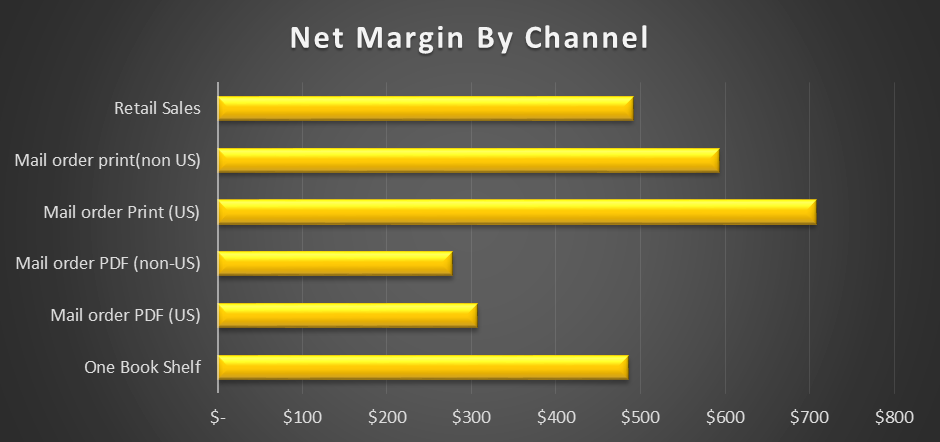

Here is an annotated version of the most recent royalty statement.

[TABLE="width: 557, align: center"] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #000000"] Venue [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #000000"] Units[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #000000"] Gross [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #000000"] Net Sale % [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #000000"] Dollars [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] One Book Shelf [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 50[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #D9D9D9"] $ 747.50 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 485.88 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 485.88 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Mail order PDF (US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 25[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 323.75 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 307.56 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 307.56 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] Mail order PDF (non-US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 20[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 199.00 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 189.05 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 278.01 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Mail order Print (US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 45[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 897.75 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 707.85 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 707.85 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] Mail order print(non US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 40[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 518.00 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 403.22 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 592.96 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Retail Sales [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 195[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 1,090.67 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 491.43 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 491.43 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 375[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $2,863.69 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 430.00 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] After Costs [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $2,433.69 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 50%[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $1,216.85 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Rate [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 0.06 [/TD] [/TR] [/TABLE] One Book Shelf are Rpgnow.com and dtrpg.com pay their publishers 65% of the headline price, and we allow 5% for card charges and refunds on our mail order site. You can also get an idea of the horrors of margins through distribution 38.5% of retail, and 25c a unit. The cost of printing this books (350 copies) was about $1500. We thought that was a good estimate of print sales for a couple of years.

What can we see? First, the writer has received 5c a word after a long, drawn-out wait. Pelgrane’s net margin was just over $1200 after four years, and investment of $2000 in printing and art and excludes the cost of Beth and Cat’s time in dealing with this book – an hour here for a reprint, then minutes here for customer feedback and marketing, plus storage, miscellaneous shipping. We still have $300 tied up in stock. So, this is what the pie looks like, excluding these Pelgrane costs.

[h=4]A Bigger Pie[/h]

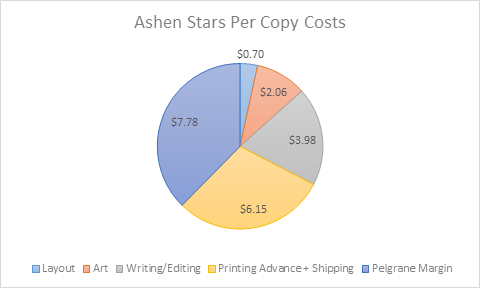

Let’s take a quick look at a hardback – Ashen Stars. It was our biggest and most expensive project then to date, and it was released before Kickstarter. As we pay freelancers long before publication, it required an up-front investment of some $15000. It required extensive rewriting with two rounds of extensive playtesting – so Robin also had to put in a long-term effort before he was paid. Then were able to start our pre-order – print only – which enabled us to pay for the print costs of some $12000 before release.

So, four years later, this is what the pie looks like across the entire print run plus PDFs. A huge chunk of the Pelgrane margin has been sunk into a new print run, which I hope will pay for itself by the end of 2017.

[h=4]Bigger Pie, Bigger Pieces[/h]

What can we take from all of this?

In many respects it’s quite simple. The reason publishers don’t pay freelancers more money is because their fixed costs per book are high, and writers are the main expense.

First, sales are low.

Publishers are selling too few books at too low a price to sustain a higher word rate.

The price of RPGs has hardly moved in 15 years. This is because there are plenty of publishers willing to produce books with very slim margins, or even at a loss, because this is a hobby business, and they just want their games out there. Demand has certainly increased, but while the RPG pie is bigger, it’s sliced into thinner pieces. Unit sales have not changed much for most products.

Second the retail price is low.

Some of it (I think) is that the market is now educated to expect low prices. $40 for a book which gives you, say, 20 hours of enjoyment seems to me like a bargain, but roleplayers who will cheerfully throw down that much on a PC game, will baulk at a higher price point. The market continues to be price sensitive. Not only that, but there are vast quantities of decent, free stuff out there.

Third, there are an unlimited number of people desperate to work for free or for lower word rates. And some of them are good.

I don’t feel guilt paying well paid professionals who work on RPG stuff as a hobby lower rates, or offering them net margin. I am much more concerned about people who write for a living. It’s peculiar, but I feel bad employing desperate people.

[h=4]What can we do as publishers?[/h]

(I am speaking here not as a starting-out creator publisher, though some of this applies to them, too.)

First, sell more books to up our margin per copy. I’m not being facetious, that is our goal for this year. We’ve spent too much time producing award-winning, excellent books and too little time selling them. Everyone wins if we sell more books.

Second, use Kickstarter, and factor in living wage rates for all freelancers, and be open about this. Kickstarter seems to open up contributors generous instincts. Where someone would inhale at a $40 price point for a book, they will scrabble to support their favourite creators with higher pledges. We can make that more clear in our stretch goals.

Finally, I think that there is a market for a Fairtrade-style mark which promises a minimum payment per word, per art piece, per page of layout, with fair terms to all contributors. I’d like to hear from freelancers what they think is reasonable, bearing in mind the figures I’ve published and their own needs. I will then stare narrow-eyed at last year’s figures, consider my employees, and see what I can do.

This article has been updated with a missing pie chart! Simon Rogers of Pelgrane Press has written an article for EN World which takes a detailed look at many of the costs of producing a roleplaying game product. He includes charts. "Last week Morrus provided a list of word rates paid by tabletop RPG publishers. He gleaned from public sources and in discussion with writers. The question arose – why are the rates low? This article centres on the economics of RPG book production and sales, but I’ll start with a preamble directed at writers and other RPG freelancers."

[h=4]Will You Get Your Pie?[/h]

When I mentioned Morrus’ list, one writer of my acquaintance said “a list of publishers who pay reliably would be a damn sight more useful.” While the word rates are fundamentally important, there’s a lot more for writers to consider when working with a publisher than the bare word rate.

- Does the publisher pay on delivery of final draft, or on publication?

- Do they pay on time and how much to you have to chase for payment?

- What happens if they don’t like the work you have done?

- Do they give you valuable feedback and edit your work?

- Looking at the other work the publisher has produced – do you want to appear alongside that work?

- Do they involve themselves in internet drama in which you don’t want to be involved?

[h=4]Should you Work for Very Little?[/h]

If you want to enter the modestly paid, astronaut-rare ranks of the full time RPG writer, what should you do? First, under no circumstances give up your day job until you command a sustainable word rate, that is words times word rate per day equals a living wage. To begin with, consider working for a lower rate, work hard and professionally and get a good reputation. Chase for money owed without the slightest guilt. Work for free on your own site, or spend your spare writing time creating pitches for publishers you like. Paizo in particular write amazing outlines for their writers.

Set yourself a time limit of, say, one year. If you are earning your target word rate by then, consider working full time. If you enjoy publishing, sales, fulfilment, handling customer queries, wrangling other creators,dealing with printers, marketing and website design, consider becoming a COP (creator-owned publisher) instead of a writer.

[h=4]A Slice of Pelgrane Pie[/h]

Now, in the interests of transparency, I’ll discuss Pelgrane Press’s RPG word rate as of the end of January 2015. Our writers on a fixed rate receive between 3c and 7c a word. As an exception we once paid Gary Gygax 10c for a short article on the Dying Earth.

In the past, I’ve taken the very easy option of employing a very few talented writers, asking them to write want they want, and paying them what they ask. We’ve supplemented these stalwarts with new writers because our in-house writers are tied up, because of the increasing number of books we produce, and that we want to work with a wider variety of voices.

A 3c-a-word writer is generally a first-time writer, or at least one who is inexperienced in the field, and such writers will always, always cost us more than a known 5c-a-word writer. We give those new writers time-consuming feedback, hone and polish their work more thoroughly, and take the risk that they will flake or one occasion plagiarise other sources. They require time and attention from our existing writers, who could otherwise be writing. So why do we do it? The answer is development. We are keen to develop new writers to work with us and other publishers – and that, for example, is how Gareth Hanrahan’s already solid writing talent was honed this way and it’s how Evil Hat’s Lenny Balsera got his first RPG writing gig (he tells me). If an enthusiastic writer with a professional attitude, who has done their homework offers us a solid pitch, there is every chance we will work with them to publish it.

[h=4]Expanding Pie[/h]

Aside from a fixed word rate, we have also, historically, offered net margin agreements to certain selected writers who were willing to accept the downside of such a deal. These are: a delay in revenue and the risk of a lower word rate delay in payment and it requires them to trust the publisher (us) not to exaggerate our costs. Where we’ve offered this deal, it’s been a choice between net margin and a word rate.

Net margin is, in principle, straightforward. The publisher adds up agreed fixed costs of production and then deducts those from the gross margin. Gross margin is the total of sales minus any per-unit costs.

The writer is then paid a percentage of this figure. In our case, that percentage to date has always been 50%.

Net margins deals have resulted in word rates of between 2c and 20c a word and the writers benefit from the long tail – the gradual continuing trickle of sales over many years.

I’m reluctant to enter into such deals now in part because of the time and tedium of calculating the royalties.

[h=4]Making the Pie[/h]

Net margin deals are tailor-made to illustrate how the production pie is sliced. I’ll use a low-end example to illustrate a simple case of production expenses and revenue for a product. The example I’ve chosen was published at a time that all work was invoiced by freelancers and was therefore easy to quantify. I never charge for my own time. It doesn’t include copy editing (which was haphazard – or I did it – which amounts to the same thing) and any unexpected expenses. The figures are accurate but I’ve adjusted dates and titles for the author’s modesty. Because this was for one of our settings, the writing was work for hire – that is we acquire the copyright. (Rights is perhaps worth another article in itself.)

Let me introduce Pitching Kittens from a Van, a thrilling supplement for the Satsuma RPG.

In 2010, an unknown writer approached me with a well written and solid adventure for the Satsuma RPG. The writer had already playtested his adventure three times, and asked if I’d be interested in publishing it. The writer said it wouldn’t be ready for at least six months for extensive and in-depth further playtesting. He exhibited a professional attitude, had done most of the work already, so I thought I’d offer him the choice between a word rate of 3c or the risk of 50% of net margin. The writer, someone who was not reliant on writing income, took the latter option.

Another six months later after rewriting external playtesting, and external playtesting, we had a book ready to be laid out.

Our fixed costs for this book were simply art and layout. Now they’d also include 0.5 to 1c a word of of copy editing and development.

We were charged $230 for art (a front cover, four quarter pages and a full page mono interior) and $100 layout (which used an existing layout template).

[h=4]Slicing the Pie[/h]

The book was 20000 words, give or take. The PDF version was $14.95, later, we added a print version at $19.95. This was in part to see if releasing a PDF then a print version would affect sales, contrary to our established view that if you release the print version first, you maximise your revenue.

Here is an annotated version of the most recent royalty statement.

[TABLE="width: 557, align: center"] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #000000"] Venue [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #000000"] Units[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #000000"] Gross [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #000000"] Net Sale % [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #000000"] Dollars [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] One Book Shelf [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 50[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #D9D9D9"] $ 747.50 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 485.88 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 485.88 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Mail order PDF (US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 25[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 323.75 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 307.56 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 307.56 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] Mail order PDF (non-US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 20[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 199.00 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 189.05 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 278.01 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Mail order Print (US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 45[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 897.75 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 707.85 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 707.85 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] Mail order print(non US) [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] 40[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 518.00 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] £ 403.22 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #d9d9d9"] $ 592.96 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Retail Sales [/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 195[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 1,090.67 [/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 491.43 [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 491.43 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 375[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $2,863.69 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 430.00 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] After Costs [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $2,433.69 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] 50%[/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $1,216.85 [/TD] [/TR] [TR] [TD="width: 156, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 43, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 90, bgcolor: #ffffff"]

[/TD] [TD="width: 99, bgcolor: #ffffff"] Rate [/TD] [TD="width: 100, bgcolor: #ffffff"] $ 0.06 [/TD] [/TR] [/TABLE] One Book Shelf are Rpgnow.com and dtrpg.com pay their publishers 65% of the headline price, and we allow 5% for card charges and refunds on our mail order site. You can also get an idea of the horrors of margins through distribution 38.5% of retail, and 25c a unit. The cost of printing this books (350 copies) was about $1500. We thought that was a good estimate of print sales for a couple of years.

Let’s take a quick look at a hardback – Ashen Stars. It was our biggest and most expensive project then to date, and it was released before Kickstarter. As we pay freelancers long before publication, it required an up-front investment of some $15000. It required extensive rewriting with two rounds of extensive playtesting – so Robin also had to put in a long-term effort before he was paid. Then were able to start our pre-order – print only – which enabled us to pay for the print costs of some $12000 before release.

So, four years later, this is what the pie looks like across the entire print run plus PDFs. A huge chunk of the Pelgrane margin has been sunk into a new print run, which I hope will pay for itself by the end of 2017.

[h=4]Bigger Pie, Bigger Pieces[/h]

What can we take from all of this?

In many respects it’s quite simple. The reason publishers don’t pay freelancers more money is because their fixed costs per book are high, and writers are the main expense.

First, sales are low.

Publishers are selling too few books at too low a price to sustain a higher word rate.

The price of RPGs has hardly moved in 15 years. This is because there are plenty of publishers willing to produce books with very slim margins, or even at a loss, because this is a hobby business, and they just want their games out there. Demand has certainly increased, but while the RPG pie is bigger, it’s sliced into thinner pieces. Unit sales have not changed much for most products.

Second the retail price is low.

Some of it (I think) is that the market is now educated to expect low prices. $40 for a book which gives you, say, 20 hours of enjoyment seems to me like a bargain, but roleplayers who will cheerfully throw down that much on a PC game, will baulk at a higher price point. The market continues to be price sensitive. Not only that, but there are vast quantities of decent, free stuff out there.

Third, there are an unlimited number of people desperate to work for free or for lower word rates. And some of them are good.

I don’t feel guilt paying well paid professionals who work on RPG stuff as a hobby lower rates, or offering them net margin. I am much more concerned about people who write for a living. It’s peculiar, but I feel bad employing desperate people.

[h=4]What can we do as publishers?[/h]

(I am speaking here not as a starting-out creator publisher, though some of this applies to them, too.)

First, sell more books to up our margin per copy. I’m not being facetious, that is our goal for this year. We’ve spent too much time producing award-winning, excellent books and too little time selling them. Everyone wins if we sell more books.

Second, use Kickstarter, and factor in living wage rates for all freelancers, and be open about this. Kickstarter seems to open up contributors generous instincts. Where someone would inhale at a $40 price point for a book, they will scrabble to support their favourite creators with higher pledges. We can make that more clear in our stretch goals.

Finally, I think that there is a market for a Fairtrade-style mark which promises a minimum payment per word, per art piece, per page of layout, with fair terms to all contributors. I’d like to hear from freelancers what they think is reasonable, bearing in mind the figures I’ve published and their own needs. I will then stare narrow-eyed at last year’s figures, consider my employees, and see what I can do.