Why would I set aside the activity I'm engaged in, when analysing that activity?If we set aside that we're playing a TTRPG, you're describing the actual thing people playing board games do for fun, as if it's a problem.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

D&D General Creativity?

- Thread starter bloodtide

- Start date

Campbell

Relaxed Intensity

@Pedantic

It is simply not true that Blades in the Dark features inevitably decaying board state. It absolutely features the risk of board state decay with every action, but it also features the potential for massive gains in board state that will outweigh those risks if skillfully managed through teamwork, leveraging character/crew build features and approaching scores from angles where you are advantaged.

Blades is almost the opposite setup from survival games like Dead of Winter. In Blades you start with basically nothing (Tier 0, No COIN, No Cohorts, No Claims, Maybe one or two allies). Throughout the course of play you are actively gaining board state (Claims, Advances, Cohorts) and yes some degradation of board state / spinning plates that you have to manage, but it is pretty manageable. These cohorts, claims, allies, tier and advances all expand the scope of what you can do dramatically.

Here are some indications of the board state we have been able to acquire through play:

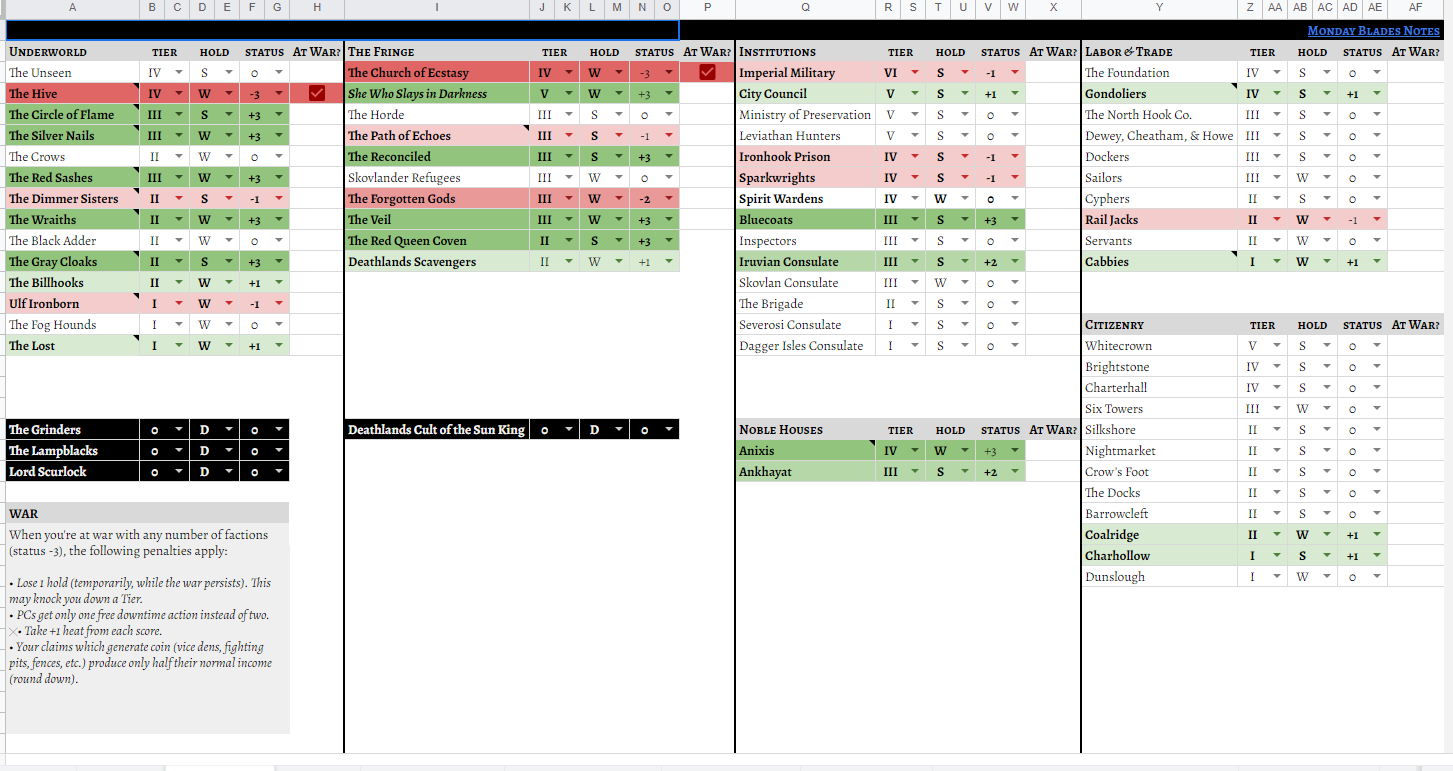

Factions

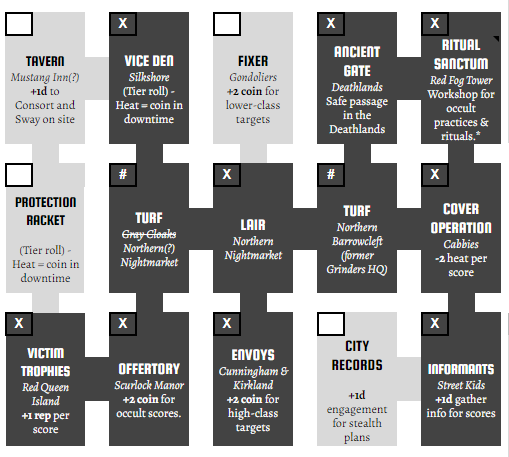

Claims

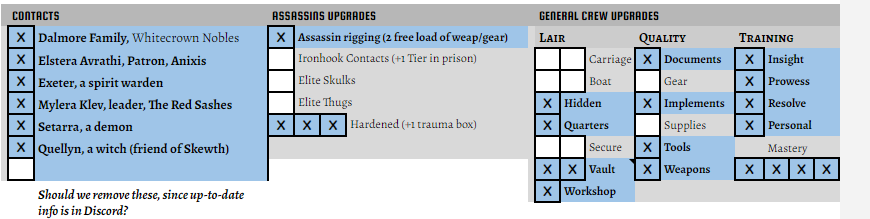

Contacts and Upgrades

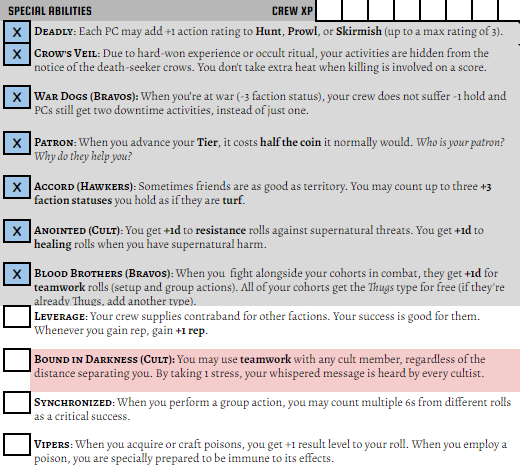

Crew Special Abilities

It is simply not true that Blades in the Dark features inevitably decaying board state. It absolutely features the risk of board state decay with every action, but it also features the potential for massive gains in board state that will outweigh those risks if skillfully managed through teamwork, leveraging character/crew build features and approaching scores from angles where you are advantaged.

Blades is almost the opposite setup from survival games like Dead of Winter. In Blades you start with basically nothing (Tier 0, No COIN, No Cohorts, No Claims, Maybe one or two allies). Throughout the course of play you are actively gaining board state (Claims, Advances, Cohorts) and yes some degradation of board state / spinning plates that you have to manage, but it is pretty manageable. These cohorts, claims, allies, tier and advances all expand the scope of what you can do dramatically.

Here are some indications of the board state we have been able to acquire through play:

Factions

Claims

Contacts and Upgrades

Crew Special Abilities

Campbell

Relaxed Intensity

I am not trying to convince anyone what game they should be playing or like, but I think it's importantly to accurately describe how the play model actually functions. Blades emphatically is not a game inevitably decaying board state nor is it a game that does not support a skilled play imperative.

Pedantic

Legend

Hopefully to avoid tautology?Why would I set aside the activity I'm engaged in, when analysing that activity?

In the broadest terms, I'm arguing that the basic structure of play from some related mediums can absolutely be applied to the TTRPG, which can differentiate itself from them without changing it. The unique features of an RPG can be expressed without changing the nature of mechanical engagement; I can use the same skills, decision making tools and get the same enjoyment from a game of Descent and a game of D&D, and they can still be meaningfully different activities, separated by other features. I've been saying consistently that I think that process of play you're describing is less fundamental than an unbounded play time and involved victory conditions. All this engagement with the fiction stuff can be offered into the actions/tools your game makes available, instead of a required part of action resolution.

Pedantic

Legend

Honestly, the BitD point feels like a whole separate thread. I'm still unpersuaded the play pattern isn't exactly the kind of spiral I hate, but I would have to dive in and play around with the different rules and model some situations to really comment, and playing a lot more of a game I didn't enjoy isn't high in my list of priorities. It's not really relevant to the broader point about engaging with RPGs mechanically.I am not trying to convince anyone what game they should be playing or like, but I think it's importantly to accurately describe how the play model actually functions. Blades emphatically is not a game inevitably decaying board state nor is it a game that does not support a skilled play imperative.

Last edited:

Baron Opal II

Legend

How can I leverage my player's creativity to have a better D&D game?

What in this thread helps me run a better D&D game?

What in this thread helps me run a better D&D game?

Okay, let's start here.Ultimately, I want to climb this mountain and light a signal fire.

You denied that negotiated imagination was fundamental to roleplaying.

So you can start to illustrate that claim by providing an example of your play in which nothing is being imagined.

AbdulAlhazred

Legend

Is that not true in 4e? If you want to be stupendously good at climbing then you take some feat and whatever. If it's a lesser obstacle you won't really even need that, but Cania is tougher, etc. In DW it's more about what fiction the table goes with.That's a mechanic that prompts the DM to change the adjectives used to describe the situation, but doesn't in any way change player decision making. On the other hand, if I can climb any wall at full speed, one handed while wielding a weapon at a DC 30 or whatever, then I can use that information to play differently than a character who can't do that, and differently than I could before I could do that.

Sure, and in DW it could work in a similar way. Climbing and lighting etc. can all be discreet steps, sub-goals on the road to some larger goal. This brings up the whole question of 'scope'. Is it a good idea to lump all that in one check, or 3 or 10? In DW none of those is wrong. It's really a question for the whole table. If the player describes it as a single action then the GM can ask for one check! How the GM frames the scene is likely to have a big influence. I think this is also a thing in 4e SCs, but the GM is more in charge there.Yes, that is getting asserted a lot.

Ultimately, I want to climb this mountain and light a signal fire. It probably signals the Rohirrim or something. To do that, presumably I need to deal with an icy cliff and who knows what else between here and there. In the model of games I like, several salient facts might include the ambient weather conditions, the height of the cliff, visibility and so on. I might then pick a tool, like say, throwing a grappling hook, hammering in some pitons, carving handholds with an ice axe, just barehanded climbing it, casting levitate, and so on.

I'll pick from that set of tools, whichever one I think will best achieve my goal here. If the cliff is short, probably that grappling hook, if I have time and a reasonable climb check, probably the pitons or ice axe, if I'm being pursued or afraid to make noise, maybe the spell slot or potion of levitate, or if I think my odds of success are good enough, maybe I'll just climb.

If there are interesting sub-goals then they can be visited, you can use any level of granularity.The advantage of mechanics that do not care what the player wants, and can only accept the input of what the player does, is that you can chart more than one path to getting what the player wants, and that these paths can be of different lengths, and that you can then make a bunch of different decisions about how you get there.

Why are those goals special, RPGs can handle much more than just that.Ideally, there's no need for the character's and players motivations to diverge. Wanting to play well, and wanting to get survive and get something done should lead them both to making the same decisions.

Sure, but I don't know what is different here between trad and story games here.You're projecting a whole series of goals on to me there that I never claimed. Generally, I think goals are a function of roleplaying. Your character cares about the people of this village and wants them not to die in the oncoming flood, your character wants revenge for the murder of their sister, your character has heard stories about this mysterious maze for years and wants to know what's inside, that layer is where you get the victory conditions for your game from, and the ability to pick new ones, and keep playing after you achieve them or they become unachievable is what differentiates an RPG from most board games.

Sure, some games, what I would call trad, like 1e AD&D work like that, the agenda is 'beat the challenge ', but there is a much wider range of agendas. To the point of the thread they all include creativity and skill.This is where it feels like we're speaking entirely separate languages. How do I play well, when the mechanic is structured to keep causing bad things to happen to me? What planning can I do to avoid them? I'm trying to describe the course of action that doesn't give you any choice but to say "you get off the island safely" when I'm done doing it, and if that doesn't occur, I want to think about why it didn't occur, and try to find something else I could have done to make it occur. At some point, I'll likely be forced to try something that has a chance not to succeed, and I can point to that risk and say "well, that was the best line of play, I think I still made the right choice" and then deal with the resulting new board state.

These posts might give you some ideas:How can I leverage my player's creativity to have a better D&D game?

What in this thread helps me run a better D&D game?

In my 4e D&D game, the invoker/wizard had a feat that granted a +2 bonus to ritual checks. I believe the publishers intended it to apply only to rituals in the mechanical sense. My friend would apply the bonus whenever he took the view that what his PC was doing was a ritual. This did not cause any problems. It did lead to that player gradually building up a picture, in the setting, of how magic works. Which goes back to the topic of this thread - creativity.

Here are just a few of the creative things that happened in my long-running 4e game, 15 to 5 or so years ago.

* A player's character died. I asked him if he wanted to keep playing the character - he did. So I asked why he might be sent back - he answered that there was something Erathis wanted him to do - a mission! I docked a Raise Dead's worth of gp from that level's treasure parcels. The character came back to life, with knowledge of where he could find the Sceptre of Law under a stone in some Nerathi ruins. Over the course f the campaign it turned out the Sceptre of Law was the Rod of 7 Parts.

* When the PCs had killed a great multi-headed red dragon, a different player had the idea of coalescing all the chaotic energy flowing out of the dragon and imbuing it into a horn, turning it into a Fire Horn.

* At much higher levels, the same player had the idea of his PC sealing the Abyss, by using his various magical abilities (a zone of energy that teleports away anyone who enters it; Stretch Spell to make it bigger, etc) amplified by his own Primordial nature.

* When fighting a beholder in a cave, a PC invoker/wizard used one of his forced movement abilities to impale the beholder on a stalactite.

* The same character, in Torog's Soul Abattoir, used his mastery of rituals to divert the flow of souls from Torog to the Raven Queen, betraying Vecna in the process.

* When the PCs were going to confront a purple worm, they took a sack of lime with them to reduce the damage from being swallowed, by partially neutralising the worm's stomach acid.

4e D&D is not a fragile game. It won't fall over as soon as the players try and play the fiction. It makes that sort of stuff easy to adjudicate. The result is high-gonzo fantasy that's fun for everyone at the table.

In the broadest terms, I'm arguing that the basic structure of play from some related mediums can absolutely be applied to the TTRPG, which can differentiate itself from them without changing it. The unique features of an RPG can be expressed without changing the nature of mechanical engagement; I can use the same skills, decision making tools and get the same enjoyment from a game of Descent and a game of D&D, and they can still be meaningfully different activities, separated by other features. I've been saying consistently that I think that process of play you're describing is less fundamental than an unbounded play time and involved victory conditions. All this engagement with the fiction stuff can be offered into the actions/tools your game makes available, instead of a required part of action resolution.

I think @chaochou's point is apposite here.You denied that negotiated imagination was fundamental to roleplaying.

So you can start to illustrate that claim by providing an example of your play in which nothing is being imagined.

The boardgame Seven Wonders has "involved victory conditions" in the sense that there are multiple dimensions of play in which victory points can be accrued, and for relatively casual players the maths at any given moment (particularly at earlier stages of play) is not easily solvable to yield an obviously superior move. There's a contrast in this respect with, say, backgammon.

But if the victory condition is "light a signal fire on top of the mountain", achieving that victory consists precisely in everyone at the table agreeing that, in the fiction, some character or other has reached the top of the mountain and has lit a fire. Which is shared imagination. Given that, in a RPG, no participant has unilateral authority to stipulate either that the fiction does or does not contain such a state of affairs within it, it's negotiated imagination.

On top of @chaochou's point:

I've played RPGs which do not involve unbounded play time. Agon is an example, with a formal structure to support its lack of unbounded play time (both at the session level and the "campaign" level). I've not played My Life With Master but believe it might be the first - certainly an early - example of a RPG with that sort of formal structure.

As well as formal structures to constrain play time, I've played RPGs with an understanding among all the participants that play time is not unbounded, and as the GM I've used my authority over the fiction to frame matters towards and then into a climax at the appropriate time.

I think in this particular post you are reiterating this point made by @LostSoul a while ago now:That's a mechanic that prompts the DM to change the adjectives used to describe the situation, but doesn't in any way change player decision making. On the other hand, if I can climb any wall at full speed, one handed while wielding a weapon at a DC 30 or whatever, then I can use that information to play differently than a character who can't do that, and differently than I could before I could do that.

But anyway: one key point that I take @AbdulAlhazred to be making, or at least pointing toward, in his discussions of Dungeon World and 4e D&D, is this: who gets to decide whether balancing on a cloud, or any other feat of heroics, will help the PC achieve the goal that the player has set for the PC?How the imagined content in the game changes in 4E as the characters gain levels isn't quite the same as it is in 3E. I am not going to pretend to have a good grasp of how this works in either system, but my gut says: in 4E the group defines the colour of their campaign as they play it; in 3E it's established when the campaign begins.

That's kind of confusing... let me see if I can clarify as I work this idea out for myself.

In 3E, climbing a hewn rock wall is DC 25. That doesn't change as the game is played (that is, as fiction is created, the game world is explored, and characters grow). Just because it's DC 120 to balance on a cloud doesn't mean that characters can't attempt it at 1st level; they'll just always fail. The relationship between colour and the reward system doesn't change over time: you know that, if you can score a DC 120 balance check, you can balance on clouds; a +1 to your Balance check brings you that much closer to success.

In 4E, I think the relationship between colour and the reward system changes: you don't know what it will mean, when you first start playing, to make a Hard Level 30 Acrobatics check. Which means that gaining levels doesn't have a defined relationship with what your PC can do in the fiction - just because your Acrobatics check has increased by 1, it doesn't mean you're that much closer to balancing on a cloud. I think the group needs to define that for themselves; as far as I can tell, this is supposed to arise organically through play, and go through major shifts as Paragon Paths and Epic Destinies enter the game.

I think @Manbearcat is pointing toward something similar in his post upthread about the technical aspects of climbing, and genre logic.

At some tables, the answer is the GM. Some RPG systems - eg 3E and 5e D&D - tend to reinforce this answer in their rulebooks and in their procedures of play.

At some tables, the answer is the table - both player(s) and GM.Some RPG systems - eg BitD, DW, 4e D&D, Agon, Burning Wheel, MHRP - tend to reinforce this answer in their rulebooks and in their procedures of play.

It is possible to have a system with "objective" difficulties (like DC120 for balancing on a cloud) that otherwise fits in the second category of pointed to: Burning Wheel is an example. But in my experience that is aesthetic and has little relevance to player agency.

Suppose a player knows that, should it be relevant to achieving their goal, their PC in this game is almost certain to be able to climb any wall at full speed, one handed while wielding a weapon. How does that give them agency? Who decides the relationship between performing such a feat, and achieving any goal?

That is all about who gets to decide the content of the fiction - in framing, and then how performing certain feats in the fiction will allow certain goals to be achieved. Negotiated imagination.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 1K

D&D General

D&D Evolutions You Like and Dislike [+]

- Replies

- 845

- Views

- 46K

D&D General

Avalor | Westmarch | 16+

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 269

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 420

Recent & Upcoming Releases

-

June 18 2026 -

October 1 2026