Alignment is, on some level, the beating heart of Dungeons & Dragons. On the other hand, it’s sort of a stupid rule. It’s like the hit point rules in that it makes for a good game experience, especially if you don’t think about it too hard. Just as Magic: the Gathering has the five colors that transcend any world or story, so alignment is a universal cosmic truth from one D&D world to the next. The deities themselves obey the pattern of alignment.

On the story side, the alignment rules contain the rudiments of roleplaying, as in portraying your character according to their personality. On the game side, it conforms to D&D’s wargaming roots, representing army lists showing who is on whose side against whom.

The 3x3 alignment grid is one part of AD&D’s legacy that we enthusiastically ported into 3E and that lives on proudly in 5E and in countless memes. Despite the centrality of alignment in D&D, other RPGs rarely copy D&D’s alignment rules, certainly not the way they have copied D&D’s rules for abilities, attack rolls, or hit points.

Alignment started as army lists in the Chainmail miniatures rules, before Dungeons & Dragons released. In those days, if you wanted to set up historical Napoleonic battles, you could look up armies in the history books to see what forces might be in play. But what about fantasy armies? Influenced by the popularity of The Lord of the Rings, Gary Gygax’s rules for medieval miniatures wargaming included a fantasy supplement. Here, to help you build opposing armies, was the list of Lawful units (good), the Chaotic units (evil), and the neutral units. Today, alignment is a roleplaying prompt for getting into character, but it started out as us-versus-them—who are the good guys and who are the bad guys?

Original D&D used the Law/Chaos binary from Chainmail, and the Greyhawk supplement had rudimentary notes about playing chaotic characters. The “referee” was urged to develop an ad hoc rule against chaotic characters cooperating indefinitely. This consideration shows how alignment started as a practical system for lining up who was on whose side but then started shifting toward being a concrete way to think about acting “in character.”

Another thing that Greyhawk said was that evil creatures (those of chaotic alignment) were as likely to turn on each other as attack a lawful party. What does a 12-year old do with that information? One DM applies the rule literally in the first encounter of his new campaign. When we fought our first group of orcs in the forest outside of town, The DM rolled randomly for each one to see whether it would attack us or its fellow orcs. That rule got applied for that first battle and none others because it was obviously stupid. In the DM’s defense, alignment was a new idea at the time.

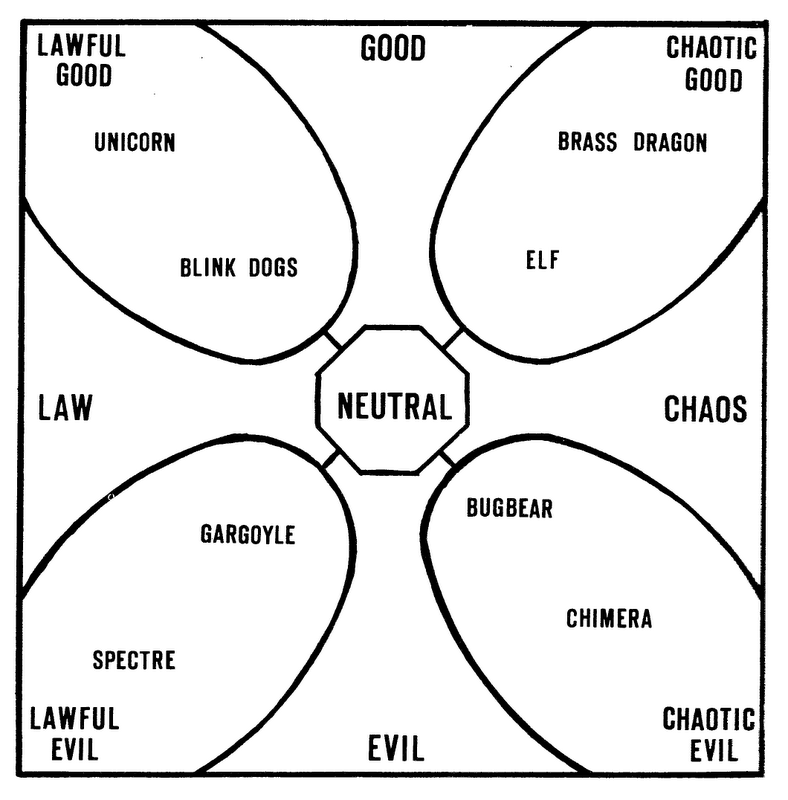

Law versus Chaos maps pretty nicely with the familiar Good versus Evil dichotomy, albeit with perhaps a more fantastic or apocalyptic tone. The Holmes Basic Set I started on, however, had a 2x2 alignment system with a fifth alignment, neutral, in the center. For my 12-year old mind, “lawful good” and “chaotic evil” made sense, and maybe “chaotic good,” but “lawful evil”? What did that even mean? I looked up “lawful,” but that didn’t help.

Our first characters were neutral because we were confused and “neutral” was the null choice. Soon, I convinced my group that we should all be lawful evil. That way we could kill everything we encountered and get the most experience points (evil) but we wouldn’t be compelled to sometimes attack each other (as chaotic evil characters would).

In general, chaotic good has been the most popular alignment since probably as soon as it was invented. The CG hero has a good heart and a free spirit. Following rules is in some sense bowing to an authority, even if it is a moral or internalized authority, and being “chaotic” means being unbowed and unyoked.

Chaotic neutral has also been popular. Players have sometimes used this alignment as an excuse to take actions that messed with the party’s plans and, not coincidentally, brought attention to the player. The character was in the party because the player was at the table, but real adventurers would never go into danger with a known wildcard along with them. This style of CG play was a face-to-face version of griefing, and it was common enough that Ryan Dancey suggested we ban it from 3E.

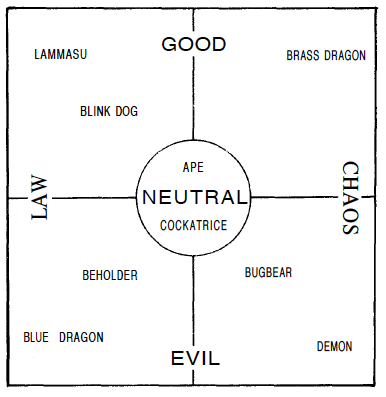

The target we had for 3E was to make a game that doubled-down on its own roots, so we embraced AD&D’s 3x3 alignment grid. Where the Holmes Basic Set listed a handful of monsters on its diagram, 3E had something more like Chainmail’s army lists, listing races, classes, and monsters on a 3x3 table.

When I was working on 3E, I was consciously working on a game for an audience that was not me. Our job was to appeal to the game’s future audience. With the alignment descriptions, however, I indulged in my personal taste for irony. The text explains why lawful good is “the best alignment you can be.” In fact, each good or neutral alignment is described as “the best,” with clear reasons given for each one. Likewise, each evil alignment is “the most dangerous,” again with a different reason for each one. This treatment was sort of a nod to the interminable debates over alignment, but the practical purpose was to make each good and neutral alignment appealing in some way.

If you ever wanted evidence that 4E wasn’t made with the demands of the fans first and foremost, recall that the game took “chaotic good” out of the rules. CG is the most popular alignment, describing a character who’s virtuous and free. The alignments in 4E were lawful good, good, neutral, evil, and chaotic evil. One on level, it made sense to eliminate odd-ball alignments that don’t make sense to newcomers, such as the “lawful evil” combination that flummoxed me when I was 12. The simpler system in 4E mapped fairly well to the Holmes Basic 2x2 grid, with two good alignments and two evil ones. In theory, it might be the best alignment system in any edition of D&D. On another level, however, the players didn’t want this change, and the Internet memes certainly didn’t want it. If it was perhaps better in theory, it was unpopular in practice.

In 5E, the alignments get a smooth, clear, spare treatment. The designers’ ability to pare down the description to the essentials demonstrates a real command of the material. This treatment of alignment is so good that I wish I’d written it.

My own games never have alignment, per se, even if the game world includes real good and evil. In Ars Magica, membership in a house is what shapes a wizard’s behavior or social position. In Over the Edge and Everway, a character’s “guiding star” is something related to the character and invented by the player, not a universal moral system. In Omega World, the only morality is survival. 13th Age, on the other hand, uses the standard system, albeit lightly. The game is a love letter to D&D, and players have come to love the alignment system, so Rob Heinsoo and I kept it. Still, a 13th Age character’s main “alignment” is in relation to the icons, which are not an abstraction but rather specific, campaign-defining NPCs.

On the story side, the alignment rules contain the rudiments of roleplaying, as in portraying your character according to their personality. On the game side, it conforms to D&D’s wargaming roots, representing army lists showing who is on whose side against whom.

The 3x3 alignment grid is one part of AD&D’s legacy that we enthusiastically ported into 3E and that lives on proudly in 5E and in countless memes. Despite the centrality of alignment in D&D, other RPGs rarely copy D&D’s alignment rules, certainly not the way they have copied D&D’s rules for abilities, attack rolls, or hit points.

Alignment started as army lists in the Chainmail miniatures rules, before Dungeons & Dragons released. In those days, if you wanted to set up historical Napoleonic battles, you could look up armies in the history books to see what forces might be in play. But what about fantasy armies? Influenced by the popularity of The Lord of the Rings, Gary Gygax’s rules for medieval miniatures wargaming included a fantasy supplement. Here, to help you build opposing armies, was the list of Lawful units (good), the Chaotic units (evil), and the neutral units. Today, alignment is a roleplaying prompt for getting into character, but it started out as us-versus-them—who are the good guys and who are the bad guys?

Original D&D used the Law/Chaos binary from Chainmail, and the Greyhawk supplement had rudimentary notes about playing chaotic characters. The “referee” was urged to develop an ad hoc rule against chaotic characters cooperating indefinitely. This consideration shows how alignment started as a practical system for lining up who was on whose side but then started shifting toward being a concrete way to think about acting “in character.”

Another thing that Greyhawk said was that evil creatures (those of chaotic alignment) were as likely to turn on each other as attack a lawful party. What does a 12-year old do with that information? One DM applies the rule literally in the first encounter of his new campaign. When we fought our first group of orcs in the forest outside of town, The DM rolled randomly for each one to see whether it would attack us or its fellow orcs. That rule got applied for that first battle and none others because it was obviously stupid. In the DM’s defense, alignment was a new idea at the time.

Law versus Chaos maps pretty nicely with the familiar Good versus Evil dichotomy, albeit with perhaps a more fantastic or apocalyptic tone. The Holmes Basic Set I started on, however, had a 2x2 alignment system with a fifth alignment, neutral, in the center. For my 12-year old mind, “lawful good” and “chaotic evil” made sense, and maybe “chaotic good,” but “lawful evil”? What did that even mean? I looked up “lawful,” but that didn’t help.

Our first characters were neutral because we were confused and “neutral” was the null choice. Soon, I convinced my group that we should all be lawful evil. That way we could kill everything we encountered and get the most experience points (evil) but we wouldn’t be compelled to sometimes attack each other (as chaotic evil characters would).

In general, chaotic good has been the most popular alignment since probably as soon as it was invented. The CG hero has a good heart and a free spirit. Following rules is in some sense bowing to an authority, even if it is a moral or internalized authority, and being “chaotic” means being unbowed and unyoked.

Chaotic neutral has also been popular. Players have sometimes used this alignment as an excuse to take actions that messed with the party’s plans and, not coincidentally, brought attention to the player. The character was in the party because the player was at the table, but real adventurers would never go into danger with a known wildcard along with them. This style of CG play was a face-to-face version of griefing, and it was common enough that Ryan Dancey suggested we ban it from 3E.

The target we had for 3E was to make a game that doubled-down on its own roots, so we embraced AD&D’s 3x3 alignment grid. Where the Holmes Basic Set listed a handful of monsters on its diagram, 3E had something more like Chainmail’s army lists, listing races, classes, and monsters on a 3x3 table.

When I was working on 3E, I was consciously working on a game for an audience that was not me. Our job was to appeal to the game’s future audience. With the alignment descriptions, however, I indulged in my personal taste for irony. The text explains why lawful good is “the best alignment you can be.” In fact, each good or neutral alignment is described as “the best,” with clear reasons given for each one. Likewise, each evil alignment is “the most dangerous,” again with a different reason for each one. This treatment was sort of a nod to the interminable debates over alignment, but the practical purpose was to make each good and neutral alignment appealing in some way.

If you ever wanted evidence that 4E wasn’t made with the demands of the fans first and foremost, recall that the game took “chaotic good” out of the rules. CG is the most popular alignment, describing a character who’s virtuous and free. The alignments in 4E were lawful good, good, neutral, evil, and chaotic evil. One on level, it made sense to eliminate odd-ball alignments that don’t make sense to newcomers, such as the “lawful evil” combination that flummoxed me when I was 12. The simpler system in 4E mapped fairly well to the Holmes Basic 2x2 grid, with two good alignments and two evil ones. In theory, it might be the best alignment system in any edition of D&D. On another level, however, the players didn’t want this change, and the Internet memes certainly didn’t want it. If it was perhaps better in theory, it was unpopular in practice.

In 5E, the alignments get a smooth, clear, spare treatment. The designers’ ability to pare down the description to the essentials demonstrates a real command of the material. This treatment of alignment is so good that I wish I’d written it.

My own games never have alignment, per se, even if the game world includes real good and evil. In Ars Magica, membership in a house is what shapes a wizard’s behavior or social position. In Over the Edge and Everway, a character’s “guiding star” is something related to the character and invented by the player, not a universal moral system. In Omega World, the only morality is survival. 13th Age, on the other hand, uses the standard system, albeit lightly. The game is a love letter to D&D, and players have come to love the alignment system, so Rob Heinsoo and I kept it. Still, a 13th Age character’s main “alignment” is in relation to the icons, which are not an abstraction but rather specific, campaign-defining NPCs.