Jon Peterson's thorough retelling of the origins of Dungeons & Dragons is less about the game and more about the two men who helped create it: Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. Their fraught relationship haunts every page as the two wage a “great war,” lining up friends and allies that would go on to influence Origins, GAMA, Gen Con, Avalon Hill, and so much more.

PLEASE NOTE: Game Wizards relies heavily on primary sources of historical record, but because some of these revelations have never before been in the public eye, this review contains spoilers!

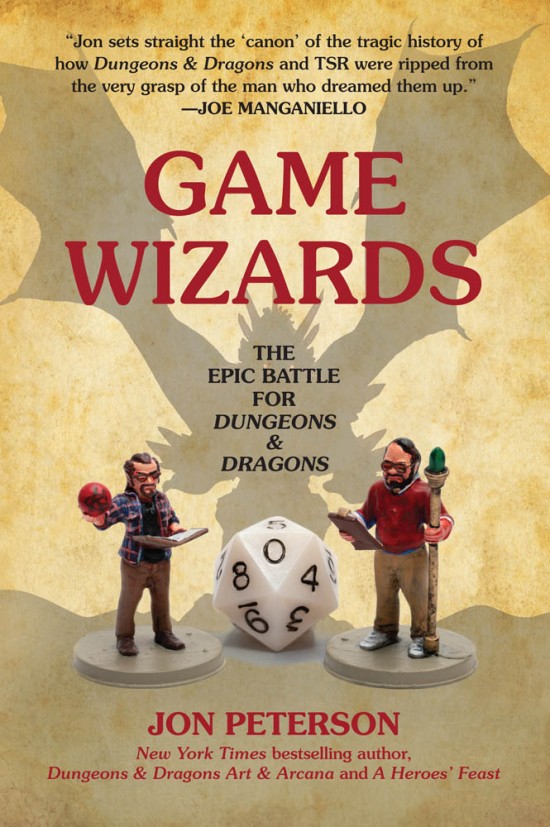

Game Wizards is as much about the evolution of D&D from a hobby to a multi-million-dollar industry as it is about Gary and Dave. It’s right there on the cover: the two miniatures of Gary (with staff and clipboard) and Dave (with sphere and book) are available for purchase at Mudpuppy Games’ webstore.

Peterson take pains to point out that there’s been a lot of spin and revisionism of how things went down, and his carefully researched and thoroughly quoted book does its best to dispel those myths. This is a clear-eyed look at both men that will likely not please fans of either.

In the early days of the game, Arneson’s work was frequently late, as was his payment for work rendered. Gygax was a relentless promoter of the game and not afraid to take over the reins when someone didn’t meet his expectations. As Peterson puts it:

It’s a revelation that Arneson had aspirations of becoming a figure caster. Before TSR became established, Arneson was interested in working with MiniFigs to carry his line of Napoleonic miniatures. At one point Gygax even offered to absorb Arneson’s figure casting business into TSR, an offer Arneson greeted with skepticism.

That skepticism has its roots in both men’s experience with Don Lowry of Guidon Games, the company that published D&D’s predecessor and fantasy miniature combat rules, Chainmail. Arneson, Gygax, and Mike Carr collaborated on anotehr Guidon Games product, Don’t Give Up the Ship. The royalties from that game, divided among the three of them, amounted to $450 for Gygax … and nothing for Arneson and Carr. Their checks bounced.

From that moment on, the “Lowry Incident” stalks Gygax and Arneson’s relationship. As Peterson puts it:

One flashpoint in that rivalry was attendance at their respective conventions. Gygax embellished Gen Con’s attendance numbers on more than one occassion so they were higher than Origins:

The “Twin Cities Coalition” voted to expand the board of directors from two (Gygax and Brian Blume) to four. It was easily voted down, but the vote sparked an argument between Gygax and Arneson. Gygax's retort to the Coalition's request for more influence over the direction of the company was essentially "employment is enough."

The aftershocks of that meeting would rattle the industry for years to come. Megarry resigned, citing the company's failure to honor the company's commitments to his Dungeon board game. The exchange also triggered a memo from Gygax about employees working in their spare time for other companies (an attack probably targeted at Arneson, who spent much of his time unsupervised and away from the office) and a new employee handbook that included rules on attendance. Soon after, a revised agreement was sent to Arneson to sign. Arneson refused to sign it and submitted a counter-proposal. When his job was reassigned to the shipping department and he was docked pay for “unsupervised travel,” Arneson resigned. The ties between the two game wizards were severed but their grievances were just beginning.

If D&D was not successful, these events would be a mere footnote. But because D&D went on to become a massive hit, Arneson's grievances would cast a long shadow over the company, ultimately culminating in a lawsuit (one of many), a royalty settlement, and a co-creator credit.

Arneson wasn't alone in his hostility to TSR. Several exhibitors who felt mistreated by TSR at Gen Con gathered together to create a new trade group, the Association of Game Manufacturers (GAMA), led by Rick Loomis of Flying Buffalo. It counted TSR rivals Avalon Hill and SPI among its members.

One of the few companies to cross TSR in the early days with an amicable resolution was M.A.R. Barker’s Empire of the Petal Throne. Peterson reveals that Barker used Dungeons & Dragons to create his own variant without securing the rights. When Arneson forwarded the game on to Gygax as a possible acquisition, Gygax was outraged … at first. TSR eventually did pick up the game for distribution, but it was a stark reminder that more competitors were coming and they could not be so easily absorbed.

A recurring theme throughout Game Wizards is that TSR, through its no-holds-barred treatment of rivals and ex-employees, frequently was its own worst enemy.

Arneson’s (sometimes frustrating) game development aspirations are also something that modern game designers will feel keenly. His D&D revision, Adventures in Fantasy, launched in fits and starts, and by the time it came to market, there were too many obstacles for it to be much of a threat to D&D. Arneson discovered that it’s not enough just to have a good idea; writing the product, putting it together, and marketing it are all critical to the game’s success. Modern game designers do all this today, but back then Arneson was learning through trial and error.

As TSR rose in prominence from a humble game company in Lake Geneva to a gaming business titan with aspirations of challenging Milton Bradley, Gygax’s legend grew with it. He was fond of telling the press that gaming was a lot like business, with the implication being that although few of the principals had business experience, they were still capable of navigating the challenging of running a successful startup. Peterson explains, in detail, how this was hubris.

TSR fell prey to what has since played out in media over-and-over with startups: nepotism, overreach, ill-fated acquisitions, employee mistreatment, financial mismanagement, and more. TSR tried to do everything and own everything at once, from miniatures to toy licensing, from novels to movies, from raising a shipwreck to needlework (yes, really). Looking back, it’s clear that TSR was ill-prepared to manage its success.

In fact, Gygax himself was ambivalent about his role. He even wrote an essay about it for Space Gamer #41, in which he grapples with the struggles to reconcile his responsibilities of being both a businessman and a gamer. By the end of the article, it's clear Gygax tried to reach a compromise by having the best of both worlds, but he wasn't nearly as invested in the business side of running a game company. The "Who Am I?" article would presage Gygax's lack of business engagement with TSR as the company grew.

Gygax's article touches on one of the many times that real-life demands intruded on his love of playing games. Throughout his career, Gygax stepped away from the hobby he loved. Early on, he simply couldn’t afford to devote all his time to it as he needed to feed his family with his day job; later, there were health-related issues. Gygax’s increasing disinterest in the business side would prove to be his downfall, as recounted in a chapter that shares the same name as Peterson’s article, “Ambush at Sheridan Springs.” By the end, Gygax had lost control of the company he helped create and, much like Arneson before him, found himself tangling with TSR over his later creative pursuits.

If anyone comes out looking better in this book, it’s Lorraine Williams. Demonized by Gygax after his ouster, much of her calculus involves saving the company from financial ruin that happened during Gygax’s tenure. With Gygax’s legacy over, the book concludes on a hopeful note that D&D is now doing better than ever.

To be fair, most D&D fans had no idea about the details of this rift. That was certainly my experience when I met Gygax at a convention in 1990. I brought my latest D&D books (unbeknownst to me, produced under Williams) to sign, but Gygax castigated a fan in front of me in line for daring to bring him the same. He was only interested in signing books during his tenure at the company. Eighteen-year-old me stepped out of line, devastated. In that one moment, my veneration of the myth was shattered.

Gygax and Arneson would, if not reconcile, at least cool on the topic of TSR. Gygax was a regular on the EN World forums and graciously answered our questions. I had plans to interview them for The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games, but both men had passed by the time I was ready to speak to them. I regret it still.

Peterson’s detailed, methodically researched accounting of TSR’s rise and fall in Game Wizards is the most accessible of his works to fans of D&D. Through Peterson’s pen, we experience the nascent days of role-playing right along with the creators, in all their triumph and folly. It’s sometimes a tough read, but it gave me a sense of closure. I suspect I’m not alone. If you have any interest in the origins of D&D, TSR, Gary, or Dave, this book is a must buy.

PLEASE NOTE: Game Wizards relies heavily on primary sources of historical record, but because some of these revelations have never before been in the public eye, this review contains spoilers!

Who Are the Wizards?

Unlike Playing at the World and The Elusive Shift, Peterson’s focus in Game Wizards is squarely on the two men credited with launching the game. It’s supplemented by Peterson’s access to a massive list of primary resources, ranging from letters to confidants to internal newsletters, panel sessions at conventions to magazine editorials published in obscurity.Game Wizards is as much about the evolution of D&D from a hobby to a multi-million-dollar industry as it is about Gary and Dave. It’s right there on the cover: the two miniatures of Gary (with staff and clipboard) and Dave (with sphere and book) are available for purchase at Mudpuppy Games’ webstore.

Peterson take pains to point out that there’s been a lot of spin and revisionism of how things went down, and his carefully researched and thoroughly quoted book does its best to dispel those myths. This is a clear-eyed look at both men that will likely not please fans of either.

In the early days of the game, Arneson’s work was frequently late, as was his payment for work rendered. Gygax was a relentless promoter of the game and not afraid to take over the reins when someone didn’t meet his expectations. As Peterson puts it:

This sums up the book nicely. The irony of course is that the differences between the two creators was likely part of what made D&D so successful. Once Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) is founded in the narrative, each chapter proceeds chronologically and concludes with “Turn Results” that include the company’s revenue and profit (along with its Barasch rating), employees, stock valuation, Gen Con attendance, and a data point that speaks volumes about the state of TSR’s affairs (e.g., “Duration of Arneson’s stay in Lake Geneva: around 11 months”).Although they had known each other for five years, working on games together, and playing them in person when their travel schedules permitted, they remained more colleagues than friends … Arneson harbored a contrarian streak, an anti-authoritarianism, which negatively disposed him to the sort of editorial prerogatives Gygax exercised: Arneson did not have the extroverted temperament of a leader, but he hated being a follower.

Games in Miniature

In the first chapter it's striking to see the boosters behind the game's success:In short, miniatures have always been inextricably linked to the marketing of D&D. This matters in the game's development, because the distributors who were interested in selling "miniature rules" were miniature manufacturers. The game was an afterthought, with the primary source of income being the miniatures themselves. This dream, of unifying miniatures and tabletop gaming in one company, would never be fully realized by TSR. Instead, Games Workshop—one of the many companies soured by their relationship with TSR—would do what TSR could not by unifying miniatures and role-playing games with the hugely successful Warhammer franchise.To stage a sprawling battle with miniatures could require dozens, or more likely hundreds of toy soldiers. Manufacturers of miniatures thus viewed rules promoting large-scale wars as something like a marketing expense: they would happily give rules away for free, or close to free, in the hopes that they would pull in bulk sales of cold metal.

It’s a revelation that Arneson had aspirations of becoming a figure caster. Before TSR became established, Arneson was interested in working with MiniFigs to carry his line of Napoleonic miniatures. At one point Gygax even offered to absorb Arneson’s figure casting business into TSR, an offer Arneson greeted with skepticism.

That skepticism has its roots in both men’s experience with Don Lowry of Guidon Games, the company that published D&D’s predecessor and fantasy miniature combat rules, Chainmail. Arneson, Gygax, and Mike Carr collaborated on anotehr Guidon Games product, Don’t Give Up the Ship. The royalties from that game, divided among the three of them, amounted to $450 for Gygax … and nothing for Arneson and Carr. Their checks bounced.

From that moment on, the “Lowry Incident” stalks Gygax and Arneson’s relationship. As Peterson puts it:

The backdrop of miniature gaming would also set the tone for Gygax’s relationship with the industry as a whole. D&D was not treated kindly by what was then the dominating force, historical wargaming. Fantasy was considered frivolous, embarrassing even, and the larger companies (Avalon Hill) and conventions (Origins) that did not embrace D&D would not be quickly forgiven or forgotten by Gygax....Arneson’s first real interaction with Gygax in business was one where payment for work was not forthcoming, and it fell on Gygax, who had arranged for the publication of Don’t Give Up the Ship, to try to explain it away—a precedent that surely informed the way Arneson perceived Gygax going forward.

One flashpoint in that rivalry was attendance at their respective conventions. Gygax embellished Gen Con’s attendance numbers on more than one occassion so they were higher than Origins:

This rivalry would expand to include TSR’s former staff.Gygax’s appetite for indulging in this sort of propaganda to attack TSR’s rivals would become one of the defining characteristics of his tenure, and from the summer of 1975 forward, it would increasingly manifest in the company’s internal and external communications. This proxy war between Avalon Hill and TSR over conventions would only escalate as the years went on and the stakes grew higher.

The First Shot of the "Great War"

Arneson was unhappy with Gygax’s plans for TSR from the start. He didn’t put down roots even when he begrudgingly moved to Lake Geneva. And Arneson was in good company with other transplants from the Twin Cities: Mike Carr, Dave Sutherland, and Dave Megarry. This split—between transplants and locals; between the more paternal Gygax who had a family to feed, and the younger employees—would come to a head in a shareholder meeting.The “Twin Cities Coalition” voted to expand the board of directors from two (Gygax and Brian Blume) to four. It was easily voted down, but the vote sparked an argument between Gygax and Arneson. Gygax's retort to the Coalition's request for more influence over the direction of the company was essentially "employment is enough."

The aftershocks of that meeting would rattle the industry for years to come. Megarry resigned, citing the company's failure to honor the company's commitments to his Dungeon board game. The exchange also triggered a memo from Gygax about employees working in their spare time for other companies (an attack probably targeted at Arneson, who spent much of his time unsupervised and away from the office) and a new employee handbook that included rules on attendance. Soon after, a revised agreement was sent to Arneson to sign. Arneson refused to sign it and submitted a counter-proposal. When his job was reassigned to the shipping department and he was docked pay for “unsupervised travel,” Arneson resigned. The ties between the two game wizards were severed but their grievances were just beginning.

If D&D was not successful, these events would be a mere footnote. But because D&D went on to become a massive hit, Arneson's grievances would cast a long shadow over the company, ultimately culminating in a lawsuit (one of many), a royalty settlement, and a co-creator credit.

Arneson wasn't alone in his hostility to TSR. Several exhibitors who felt mistreated by TSR at Gen Con gathered together to create a new trade group, the Association of Game Manufacturers (GAMA), led by Rick Loomis of Flying Buffalo. It counted TSR rivals Avalon Hill and SPI among its members.

One of the few companies to cross TSR in the early days with an amicable resolution was M.A.R. Barker’s Empire of the Petal Throne. Peterson reveals that Barker used Dungeons & Dragons to create his own variant without securing the rights. When Arneson forwarded the game on to Gygax as a possible acquisition, Gygax was outraged … at first. TSR eventually did pick up the game for distribution, but it was a stark reminder that more competitors were coming and they could not be so easily absorbed.

A recurring theme throughout Game Wizards is that TSR, through its no-holds-barred treatment of rivals and ex-employees, frequently was its own worst enemy.

Business Games

For those of us who have storefronts on DriveThruRPG and DMs Guild, there’s something comforting about the early days of TSR. Gygax and co. initially ran a tight ship with no expectation of profit, and reinvested all their returns into the games themselves. Although they were dealing with print instead of digital products, there’s a lot in common with the thousands of tabletop gaming entrepreneurs who pepper the digital landscape today.Arneson’s (sometimes frustrating) game development aspirations are also something that modern game designers will feel keenly. His D&D revision, Adventures in Fantasy, launched in fits and starts, and by the time it came to market, there were too many obstacles for it to be much of a threat to D&D. Arneson discovered that it’s not enough just to have a good idea; writing the product, putting it together, and marketing it are all critical to the game’s success. Modern game designers do all this today, but back then Arneson was learning through trial and error.

As TSR rose in prominence from a humble game company in Lake Geneva to a gaming business titan with aspirations of challenging Milton Bradley, Gygax’s legend grew with it. He was fond of telling the press that gaming was a lot like business, with the implication being that although few of the principals had business experience, they were still capable of navigating the challenging of running a successful startup. Peterson explains, in detail, how this was hubris.

TSR fell prey to what has since played out in media over-and-over with startups: nepotism, overreach, ill-fated acquisitions, employee mistreatment, financial mismanagement, and more. TSR tried to do everything and own everything at once, from miniatures to toy licensing, from novels to movies, from raising a shipwreck to needlework (yes, really). Looking back, it’s clear that TSR was ill-prepared to manage its success.

In fact, Gygax himself was ambivalent about his role. He even wrote an essay about it for Space Gamer #41, in which he grapples with the struggles to reconcile his responsibilities of being both a businessman and a gamer. By the end of the article, it's clear Gygax tried to reach a compromise by having the best of both worlds, but he wasn't nearly as invested in the business side of running a game company. The "Who Am I?" article would presage Gygax's lack of business engagement with TSR as the company grew.

Gygax's article touches on one of the many times that real-life demands intruded on his love of playing games. Throughout his career, Gygax stepped away from the hobby he loved. Early on, he simply couldn’t afford to devote all his time to it as he needed to feed his family with his day job; later, there were health-related issues. Gygax’s increasing disinterest in the business side would prove to be his downfall, as recounted in a chapter that shares the same name as Peterson’s article, “Ambush at Sheridan Springs.” By the end, Gygax had lost control of the company he helped create and, much like Arneson before him, found himself tangling with TSR over his later creative pursuits.

If anyone comes out looking better in this book, it’s Lorraine Williams. Demonized by Gygax after his ouster, much of her calculus involves saving the company from financial ruin that happened during Gygax’s tenure. With Gygax’s legacy over, the book concludes on a hopeful note that D&D is now doing better than ever.

Should You Buy It?

Peterson is careful to point out that many of the starring characters of TSR’s rise had good reason to embellish how things went down. His methodical accounting of primary sources demolishes the myths they created. If you believed them, you’re not going to like Game Wizards.To be fair, most D&D fans had no idea about the details of this rift. That was certainly my experience when I met Gygax at a convention in 1990. I brought my latest D&D books (unbeknownst to me, produced under Williams) to sign, but Gygax castigated a fan in front of me in line for daring to bring him the same. He was only interested in signing books during his tenure at the company. Eighteen-year-old me stepped out of line, devastated. In that one moment, my veneration of the myth was shattered.

Gygax and Arneson would, if not reconcile, at least cool on the topic of TSR. Gygax was a regular on the EN World forums and graciously answered our questions. I had plans to interview them for The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games, but both men had passed by the time I was ready to speak to them. I regret it still.

Peterson’s detailed, methodically researched accounting of TSR’s rise and fall in Game Wizards is the most accessible of his works to fans of D&D. Through Peterson’s pen, we experience the nascent days of role-playing right along with the creators, in all their triumph and folly. It’s sometimes a tough read, but it gave me a sense of closure. I suspect I’m not alone. If you have any interest in the origins of D&D, TSR, Gary, or Dave, this book is a must buy.