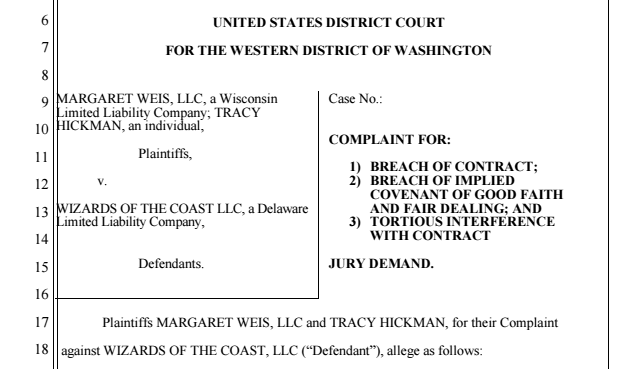

For fans of the Dragonlance D&D setting, there's some mixed news which has just hit a court in Washington State: it seems that there's a new Dragonlance trilogy of books which was (until recently) being written; but we may never see them. On 16th October 2020, a lawsuit was filed in the US District Court by Dragonlance authors Weis and Hickman asserting an unlawful breach of contract by WotC regarding the licensing of a new series of Dragonlance novels. Indeed, it appears that the first of three novels, Dragons of Deceit, has already been written, as has Book 2, Dragons of Fate.

www.documentcloud.org

www.documentcloud.org

The Lawsuit

From the documents it appears that in March 2019 a new Dragonlance trilogy was licensed by WotC; Weis and Hickman wrote a book called Dragons of Deceit, and the draft of a second called Dragons of Fate, and then WotC terminated the contract in August 2020.

The suit asserts that the termination was unlawful, and "violated multiple aspects of the License Agreement". It goes on to assert that the reasons for the termination were due to WotC being "embroiled in a series of embarrassing public disputes whereby its non-Dragonlance publications were excoriated for racism and sexism. Moreover, the company itself was vilified by well-publicized allegations of misogyny and racist hiring and employment practices by and with respect to artists and employees unrelated to Dragonlance."

Delving into the attached document, all seemed to be going to plan until June 2020, at which the team overseeing the novels was replaced by WotC. The document cites public controversies involving one of the new team, issues with Magic: The Gathering, Orion Black's public complaints about the company's hiring practices, and more. Eventually, in August 2020, the suit alleges that during a telephone call, WotC terminated the agreement with the statement "We are not moving toward breach, but we will not approve any further drafts.”

Ending the Agreement

The suit notes that "None of the termination provisions were triggered, nor was there a claim of material breach much less written notice thereof, nor was a 30-day cure period initiated." The situation appears to be that while the agreement could not in itself be unilaterally 'terminated' in this way, WotC was able to simply not approve any further drafts (including the existing draft). The text of that allegation reads:

Basically, while the contract itself could not be terminated, refusing to approve work amounts to an 'effective' termination. Weis and Hickman note that the license itself does not allow for arbitrary termination. The following section of the document is relevant:

So, the agreement apparently requires WotC to allow W&H to fix any approval-based concerns. Notwithstanding that WotC might be unsatisfied with W&H's previous rewrites, the decision in advance to simply not approve drafts without giving them this chance to rewrite appears to be the crux of the issue, and this is what the writers are alleging is the breach of contract.

Weis & Hickman are demanding a jury trial and are suing for breach of contract, damages, and a court order to require WotC to fulfill its end of the agreement. They cite years of work, and millions of dollars.

Licensing Agreements

So how does all this work? Obviously we don't have access to the original contract, so we don't know the exact terms of the licensing agreement; similarly, we are hearing one side of the story here.

The arrangement appears to have been a licensing arrangement -- that is, Weis & Hickman will have licensed the Dragonlance IP from WotC, and have arranged with Penguin Random House to publish the trilogy. It's not work-for-hire, or work commissioned by and paid for by WotC; on the contrary, in most licensing deals, the licensee pays the licensor. Indeed in this case, the document indicates that Penguin Random House paid Weis & Hickman an advance in April 2019, and W&H subsequently paid WotC (presumably a percentage of this).

Licensing agreements vary, but they often share similar features. These usually involve the licensee paying the IP owner a licensing fee or an advance on royalties at the start of the license, and sometimes annually or at certain milestones. Thereafter, the licensee also often pays the IP holder royalties on the actual book profits. We don't know the exact details of this licensing agreement, but it seems to share some of those features.

Tortious Interference

There's another wrinkle, a little later. The document says that a second payment was due on November 2019 -- similarly it would be paid to W&H by Penguin Random House, who would then pay WotC. It appears that PRH did not make that second payment to W&H. W&H later say they discovered that WotC was talking directly to Penguin Random House about editorial topics, which is what the term 'tortious interference with contract' is referring to.

What Happened?

Throughout the process, WotC asked for 'sensitivity rewrites'. These appear to include four points, including the use of a love potion, and other "concerns of sexism, inclusivity and potential negative connotations of certain character names." W&H content that they provided the requested rewrites.

One section which might provide some insight into the process is this:

It's hard to interpret that without the context of the full conversations that took place, but it sounds like WotC, in response to the previously-mentioned publicity storm it has been enduring regarding inclusivity, wanted to ensure that this new trilogy of books would not exacerbate the problems. We know they asked for some rewrites, and W&H say they complied, but the phrase "within the framework of their novels" sounds like a conditional description. It could be that WotC was not satisfied with the rewrites, and that W&H were either unable or unwilling to alter the story or other details to the extent that they were asked to. There's a lot to unpack in that little "within the framework of their novels" phrase, and we can only speculate.

It sounds like this then resulted in WotC essentially backing out of the whole deal by simply declaring that they would refuse to approve any further drafts, in the absence of an actual contractual clause that would accommodate this situation.

What we do know is that there are two completed drafts of new Dragonlance novels out there. Whether we'll ever get to read them is another question! Dragons of Deceit is complete, Dragons of Fate has a draft, and the third book has been outlined.

DocumentCloud

The Lawsuit

From the documents it appears that in March 2019 a new Dragonlance trilogy was licensed by WotC; Weis and Hickman wrote a book called Dragons of Deceit, and the draft of a second called Dragons of Fate, and then WotC terminated the contract in August 2020.

The suit asserts that the termination was unlawful, and "violated multiple aspects of the License Agreement". It goes on to assert that the reasons for the termination were due to WotC being "embroiled in a series of embarrassing public disputes whereby its non-Dragonlance publications were excoriated for racism and sexism. Moreover, the company itself was vilified by well-publicized allegations of misogyny and racist hiring and employment practices by and with respect to artists and employees unrelated to Dragonlance."

NATURE OF THE ACTION

1. Margaret Weis (“Weis”) and Tracy Hickman (“Hickman”) (collectively with Margaret Weis, LLC, “Plaintiff-Creators”) are among the most widely-read and successful living authors and world-creators in the fantasy fiction arena. Over thirty-five years ago, Plaintiff- Creators conceived of and created the Dragonlance universe—a campaign setting for the “Dungeons & Dragons” roleplaying game, the rights to which are owned by Defendant. (In Dungeons & Dragons, gamers assume roles within a storyline and embark on a series of adventures—a “campaign”—in the context of a particular campaign setting.)

2. Plaintiff-Creators’ conception and development of the Dragonlance universe has given rise to, among other things, gaming modules, video games, merchandise, comic books, films, and a series of books set in the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy world. While other authors have been invited to participate in creating over 190 separate fictional works within the Dragonlance universe, often with Plaintiff-Creators as editors, Weis’s and Hickman’s own works remain by far the most familiar and salable. Their work has inspired generations of gamers, readers and enthusiasts, beginning in 1984 when they published their groundbreaking novel Dragons of Autumn Twilight, which launched the Dragonlance Chronicles trilogy. Their books have sold more than thirty million copies, and their Dragonlance World of Krynn is arguably the most successful and popular world in shared fiction, rivaled in the fantasy realm only by the renowned works created by J.R.R. Tolkien (which do not involve a shared fictional world). Within the Dragonlance universe, Plaintiff-Creators have authored or edited 31 separate books, short story anthologies, game materials, and art and reference books in a related series of works all dedicated to furthering the Dungeons & Dragons/Dragonlance brand.

3. In or around 2017, Plaintiff-Creators learned that Defendant was receptive to licensing its properties with established authors to revitalize the Dungeons & Dragons brand. After a ten-year hiatus, Plaintiff-Creators approached Defendant and began negotiating for a license to author a new Dragonlance trilogy. Plaintiff-Creators viewed the new trilogy as the capstone to their life’s work and as an offering to their multitude of fans who had clamored for a continuation of the series. Given that the Dragonlance series intellectual property is owned by Defendant, there could be no publication without a license. In March, 2019, the negotiations between the parties hereto culminated in new written licensing agreement whereby Weis and Hickman were to personally author and publish a new Dragonlance trilogy in conjunction with Penguin Random House, a highly prestigious book publisher (the “License Agreement”).

4. By the time the License Agreement was signed, Defendant had a full overview of the story and story arc, with considerable detail, of the planned trilogy. Defendant knew exactly the nature of the work it was going to receive and had pre-approved Penguin Random House as the publisher. Indeed, Defendant was at all times aware of the contract between Penguin Random House and Plaintiff-Creators (the “Publishing Agreement”) and its terms. In fact, the License Agreement expressly refers to the Publishing Agreement.

5. By June 2019, Defendant received and approved a full outline of the first contracted book in the trilogy (“Book 1”) and by November 2019 the publisher accepted a manuscript for Book 1. Plaintiff-Creators in turn sent the Book 1 manuscript to Defendant, who approved it in January 2020. In the meantime, Defendant was already approving foreign translation rights and encouraging Plaintiff-Creators to work on the subsequent novels.

6. During the development and writing process, Plaintiff-Creators met all contractual milestones and received all requisite approvals from Defendant. Defendant at all times knew that Hickman and Weis had devoted their full attention and time commitment to completing Book 1 and the trilogy as a whole in conformity with their contractual obligations. During the writing process, Defendant proposed certain changes in keeping with the modern-day zeitgeist of a more inclusive and diverse story-world. At each step, Plaintiff-Creators timely accommodated such requests, and all others, within the framework of their novels. This collaborative process tracks with Section 2(a)(iii) of the License Agreement, which requires Defendant to approve Plaintiff- Creators’ drafts or, alternatively, provide written direction as to the changes that will result in Defendant’s approval of a draft.

7. On or about August 13, 2020, Defendant participated in a telephone conference with Plaintiff-Creators’ agents, which was attended by Defendant’s highest-level executives and attorneys as well as PRH executives and counsel. At that meeting, Defendant declared that it would not approve any further Drafts of Book 1 or any subsequent works in the trilogy, effectively repudiating and terminating the License Agreement. No reason was provided for the termination. (In any event, no material breaches or defaults were indicated or existed upon which to predicate a termination.) The termination was wholly arbitrary and without contractual basis. The termination was unlawful and in violation of multiple aspects of the License Agreement (arguably almost every part of it, in fact). The termination also had the knowing and premeditated effect of precluding publication and destroying the value of Plaintiff-Creators’ work—not to mention their publishing deal with Penguin Random House.

8. Defendant’s acts and failures to act breached the License Agreement and were made in stunning and brazen bad faith. Defendant acted with full knowledge that its unilateral decision would not only interfere with, but also would lay waste to, the years of work that Plaintiff-Creators had, to that point, put into the project. Given that the obligation to obtain a publisher was part and parcel of the License Agreement, Defendant was fully cognizant that its backdoor termination of the License Agreement would nullify the millions of dollars in remuneration to which Plaintiff-Creators were entitled from their publishing contract.

9. As Plaintiff-Creators subsequently learned, Defendant’s arbitrary decision to terminate the License Agreement—and thereby the book publishing contract—was based on events that had nothing to do with either the Work or Plaintiff-Creators. In fact, at nearly the exact point in time of the termination, Defendant was embroiled in a series of embarrassing public disputes whereby its non-Dragonlance publications were excoriated for racism and sexism. Moreover, the company itself was vilified by well-publicized allegations of misogyny and racist hiring and employment practices by and with respect to artists and employees unrelated to Dragonlance. Plaintiff-Creators are informed and believe, and based thereon allege, that a decision was made jointly by Defendant and its parent company, Hasbro, Inc., to deflect any possible criticism or further public outcry regarding Defendant’s other properties by effectively killing the Dragonlance deal with Plaintiff-Creators. The upshot of that was to inflict knowing, malicious and oppressive harm to Plaintiff-Creators and to interfere with their third- party contractual obligations, all to Plaintiff-Creator’s severe detriment and distress.

1. Margaret Weis (“Weis”) and Tracy Hickman (“Hickman”) (collectively with Margaret Weis, LLC, “Plaintiff-Creators”) are among the most widely-read and successful living authors and world-creators in the fantasy fiction arena. Over thirty-five years ago, Plaintiff- Creators conceived of and created the Dragonlance universe—a campaign setting for the “Dungeons & Dragons” roleplaying game, the rights to which are owned by Defendant. (In Dungeons & Dragons, gamers assume roles within a storyline and embark on a series of adventures—a “campaign”—in the context of a particular campaign setting.)

2. Plaintiff-Creators’ conception and development of the Dragonlance universe has given rise to, among other things, gaming modules, video games, merchandise, comic books, films, and a series of books set in the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy world. While other authors have been invited to participate in creating over 190 separate fictional works within the Dragonlance universe, often with Plaintiff-Creators as editors, Weis’s and Hickman’s own works remain by far the most familiar and salable. Their work has inspired generations of gamers, readers and enthusiasts, beginning in 1984 when they published their groundbreaking novel Dragons of Autumn Twilight, which launched the Dragonlance Chronicles trilogy. Their books have sold more than thirty million copies, and their Dragonlance World of Krynn is arguably the most successful and popular world in shared fiction, rivaled in the fantasy realm only by the renowned works created by J.R.R. Tolkien (which do not involve a shared fictional world). Within the Dragonlance universe, Plaintiff-Creators have authored or edited 31 separate books, short story anthologies, game materials, and art and reference books in a related series of works all dedicated to furthering the Dungeons & Dragons/Dragonlance brand.

3. In or around 2017, Plaintiff-Creators learned that Defendant was receptive to licensing its properties with established authors to revitalize the Dungeons & Dragons brand. After a ten-year hiatus, Plaintiff-Creators approached Defendant and began negotiating for a license to author a new Dragonlance trilogy. Plaintiff-Creators viewed the new trilogy as the capstone to their life’s work and as an offering to their multitude of fans who had clamored for a continuation of the series. Given that the Dragonlance series intellectual property is owned by Defendant, there could be no publication without a license. In March, 2019, the negotiations between the parties hereto culminated in new written licensing agreement whereby Weis and Hickman were to personally author and publish a new Dragonlance trilogy in conjunction with Penguin Random House, a highly prestigious book publisher (the “License Agreement”).

4. By the time the License Agreement was signed, Defendant had a full overview of the story and story arc, with considerable detail, of the planned trilogy. Defendant knew exactly the nature of the work it was going to receive and had pre-approved Penguin Random House as the publisher. Indeed, Defendant was at all times aware of the contract between Penguin Random House and Plaintiff-Creators (the “Publishing Agreement”) and its terms. In fact, the License Agreement expressly refers to the Publishing Agreement.

5. By June 2019, Defendant received and approved a full outline of the first contracted book in the trilogy (“Book 1”) and by November 2019 the publisher accepted a manuscript for Book 1. Plaintiff-Creators in turn sent the Book 1 manuscript to Defendant, who approved it in January 2020. In the meantime, Defendant was already approving foreign translation rights and encouraging Plaintiff-Creators to work on the subsequent novels.

6. During the development and writing process, Plaintiff-Creators met all contractual milestones and received all requisite approvals from Defendant. Defendant at all times knew that Hickman and Weis had devoted their full attention and time commitment to completing Book 1 and the trilogy as a whole in conformity with their contractual obligations. During the writing process, Defendant proposed certain changes in keeping with the modern-day zeitgeist of a more inclusive and diverse story-world. At each step, Plaintiff-Creators timely accommodated such requests, and all others, within the framework of their novels. This collaborative process tracks with Section 2(a)(iii) of the License Agreement, which requires Defendant to approve Plaintiff- Creators’ drafts or, alternatively, provide written direction as to the changes that will result in Defendant’s approval of a draft.

7. On or about August 13, 2020, Defendant participated in a telephone conference with Plaintiff-Creators’ agents, which was attended by Defendant’s highest-level executives and attorneys as well as PRH executives and counsel. At that meeting, Defendant declared that it would not approve any further Drafts of Book 1 or any subsequent works in the trilogy, effectively repudiating and terminating the License Agreement. No reason was provided for the termination. (In any event, no material breaches or defaults were indicated or existed upon which to predicate a termination.) The termination was wholly arbitrary and without contractual basis. The termination was unlawful and in violation of multiple aspects of the License Agreement (arguably almost every part of it, in fact). The termination also had the knowing and premeditated effect of precluding publication and destroying the value of Plaintiff-Creators’ work—not to mention their publishing deal with Penguin Random House.

8. Defendant’s acts and failures to act breached the License Agreement and were made in stunning and brazen bad faith. Defendant acted with full knowledge that its unilateral decision would not only interfere with, but also would lay waste to, the years of work that Plaintiff-Creators had, to that point, put into the project. Given that the obligation to obtain a publisher was part and parcel of the License Agreement, Defendant was fully cognizant that its backdoor termination of the License Agreement would nullify the millions of dollars in remuneration to which Plaintiff-Creators were entitled from their publishing contract.

9. As Plaintiff-Creators subsequently learned, Defendant’s arbitrary decision to terminate the License Agreement—and thereby the book publishing contract—was based on events that had nothing to do with either the Work or Plaintiff-Creators. In fact, at nearly the exact point in time of the termination, Defendant was embroiled in a series of embarrassing public disputes whereby its non-Dragonlance publications were excoriated for racism and sexism. Moreover, the company itself was vilified by well-publicized allegations of misogyny and racist hiring and employment practices by and with respect to artists and employees unrelated to Dragonlance. Plaintiff-Creators are informed and believe, and based thereon allege, that a decision was made jointly by Defendant and its parent company, Hasbro, Inc., to deflect any possible criticism or further public outcry regarding Defendant’s other properties by effectively killing the Dragonlance deal with Plaintiff-Creators. The upshot of that was to inflict knowing, malicious and oppressive harm to Plaintiff-Creators and to interfere with their third- party contractual obligations, all to Plaintiff-Creator’s severe detriment and distress.

Delving into the attached document, all seemed to be going to plan until June 2020, at which the team overseeing the novels was replaced by WotC. The document cites public controversies involving one of the new team, issues with Magic: The Gathering, Orion Black's public complaints about the company's hiring practices, and more. Eventually, in August 2020, the suit alleges that during a telephone call, WotC terminated the agreement with the statement "We are not moving toward breach, but we will not approve any further drafts.”

Ending the Agreement

The suit notes that "None of the termination provisions were triggered, nor was there a claim of material breach much less written notice thereof, nor was a 30-day cure period initiated." The situation appears to be that while the agreement could not in itself be unilaterally 'terminated' in this way, WotC was able to simply not approve any further drafts (including the existing draft). The text of that allegation reads:

Not only was Defendant’s statement that “we will not approve any future drafts” a clumsy effort to circumvent the termination provisions (because, of course, there was no ground for termination), it undermined the fundamental structure of the contractual relationship whereby the Defendant-Licensor would provide Plaintiff-Creators the opportunity and roadmap to “fix”/rewrite/cure any valid concerns related to the protection of the Dungeons & Dragons brand with respect to approvals. In any event, Defendant had already approved the essential storylines, plots, characters, creatures, and lore for the new Dragonlance trilogy when it approved Plaintiff-Creators’ previous drafts and story arc, which were complete unto themselves, were delivered prior to execution of the License Agreement, and are acknowledged in the text of the License Agreement. In other words, Defendant’s breach had nothing to do with Plaintiff-Creators’ work; it was driven by Defendant’s response to its own, unrelated corporate public relations problems—possibly encouraged or enacted by its corporate parent, Hasbro, Inc.

Basically, while the contract itself could not be terminated, refusing to approve work amounts to an 'effective' termination. Weis and Hickman note that the license itself does not allow for arbitrary termination. The following section of the document is relevant:

Nothing in the above provision allows Defendant to terminate the License Agreement based on Defendant’s failure to provide approval. To the contrary, should Defendant find any aspect of the Draft to be unacceptable, Defendant has an affirmative duty under contract to provide “reasonable detail” of any changes Plaintiff-Creators must make, which changes will result in Defendant’s approval of the manuscript. Accordingly, for Defendant to make the blanket statement that it will never approve any Drafts going forward is, by itself, a breach of the license agreement.

So, the agreement apparently requires WotC to allow W&H to fix any approval-based concerns. Notwithstanding that WotC might be unsatisfied with W&H's previous rewrites, the decision in advance to simply not approve drafts without giving them this chance to rewrite appears to be the crux of the issue, and this is what the writers are alleging is the breach of contract.

Weis & Hickman are demanding a jury trial and are suing for breach of contract, damages, and a court order to require WotC to fulfill its end of the agreement. They cite years of work, and millions of dollars.

Licensing Agreements

Defendant acted with full knowledge that its unilateral decision would not only interfere with, but also would lay waste to, the years of work that Plaintiff-Creators had, to that point, put into the project. Given that the obligation to obtain a publisher was part and parcel of the License Agreement, Defendant was fully cognizant that its backdoor termination of the License Agreement would nullify the millions of dollars in remuneration to which Plaintiff-Creators were entitled from their publishing contract.

So how does all this work? Obviously we don't have access to the original contract, so we don't know the exact terms of the licensing agreement; similarly, we are hearing one side of the story here.

The arrangement appears to have been a licensing arrangement -- that is, Weis & Hickman will have licensed the Dragonlance IP from WotC, and have arranged with Penguin Random House to publish the trilogy. It's not work-for-hire, or work commissioned by and paid for by WotC; on the contrary, in most licensing deals, the licensee pays the licensor. Indeed in this case, the document indicates that Penguin Random House paid Weis & Hickman an advance in April 2019, and W&H subsequently paid WotC (presumably a percentage of this).

Licensing agreements vary, but they often share similar features. These usually involve the licensee paying the IP owner a licensing fee or an advance on royalties at the start of the license, and sometimes annually or at certain milestones. Thereafter, the licensee also often pays the IP holder royalties on the actual book profits. We don't know the exact details of this licensing agreement, but it seems to share some of those features.

On March 29, 2019, Plaintiff-Creators and PRH entered into the Publishing Agreement. PRH remitted the signing payment due under the Publishing Agreement to Plaintiff- Creators in April 2019. Per the terms of the License Agreement, Plaintiff-Creators in turn remitted a portion of the signing payment to Defendant—an amount Defendant continues to retain despite having effectively terminated the License Agreement.

Tortious Interference

On information and belief, Defendant also engaged in back-channel activities to disrupt the Publishing Agreement by convincing PRH that Defendant would prevent Plaintiff- Creators from performing under the Publishing Agreement

There's another wrinkle, a little later. The document says that a second payment was due on November 2019 -- similarly it would be paid to W&H by Penguin Random House, who would then pay WotC. It appears that PRH did not make that second payment to W&H. W&H later say they discovered that WotC was talking directly to Penguin Random House about editorial topics, which is what the term 'tortious interference with contract' is referring to.

By June 2019, Defendant/Hasbro expressly approved a detailed outline of Book 1. In November 2019, PRH indicated that the complete manuscript of Book 1 was accepted and it would push through the second payment due on the Publishing Agreement. At that time, Plaintiff-Creators submitted the complete manuscript of Book 1 to Defendant/Hasbro who expressly approved the Book 1 manuscript in January 2020. Inexplicably, and despite Plaintiff- Creators’ repeated request, PRH never actually delivered the second payment due on approval of the Book 1 manuscript.

What Happened?

Throughout the process, WotC asked for 'sensitivity rewrites'. These appear to include four points, including the use of a love potion, and other "concerns of sexism, inclusivity and potential negative connotations of certain character names." W&H content that they provided the requested rewrites.

One section which might provide some insight into the process is this:

During the writing process, Defendant proposed certain changes in keeping with the modern-day zeitgeist of a more inclusive and diverse story-world. At each step, Plaintiff-Creators timely accommodated such requests, and all others, within the framework of their novels.

It's hard to interpret that without the context of the full conversations that took place, but it sounds like WotC, in response to the previously-mentioned publicity storm it has been enduring regarding inclusivity, wanted to ensure that this new trilogy of books would not exacerbate the problems. We know they asked for some rewrites, and W&H say they complied, but the phrase "within the framework of their novels" sounds like a conditional description. It could be that WotC was not satisfied with the rewrites, and that W&H were either unable or unwilling to alter the story or other details to the extent that they were asked to. There's a lot to unpack in that little "within the framework of their novels" phrase, and we can only speculate.

It sounds like this then resulted in WotC essentially backing out of the whole deal by simply declaring that they would refuse to approve any further drafts, in the absence of an actual contractual clause that would accommodate this situation.

What we do know is that there are two completed drafts of new Dragonlance novels out there. Whether we'll ever get to read them is another question! Dragons of Deceit is complete, Dragons of Fate has a draft, and the third book has been outlined.