You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Fall Ceramic DM - Final Round Judgment Posted!

- Thread starter mythago

- Start date

dreaded_beast

First Post

Apologies everyone.

I will not have Internet access for a while and I am not finished with my story.

Sorry, but I must quit this round.

Good game everyone!

I will not have Internet access for a while and I am not finished with my story.

Sorry, but I must quit this round.

Good game everyone!

RangerWickett

Legend

Hunger

By Ryan Nock

Flesh is weak, the adults taught. Spirit is eternal, they insisted. One’s body is suffering until freedom, and Rawann believed that. But every adult had once been young, and all had undergone the Trial of Hunger. They appreciated that the weakness of flesh has its benefits, though they could no longer enjoy them.

The celebration cookfires filled the darkness of Rawann’s village with a joyous glow, but as his elders danced and sang for his rise to maturity, Rawann fought the pangs of his stomach.

“This night,” the shaman promised, “you shall hunger your last.”

The shaman smeared seasoned blood on his forehead, and Rawann nodded, hopefully.

This meal would bless him on his trial, and if he could survive it, the magic would sustain him for the rest of his life, as it did all the adults of his tribe. Food had been scarce all his life, and for countless generations before him, scarce since the scorching of the sky, scarce forever.

How the village had brought together foods of so many scents bewildered Rawann, frightened him. The shaman’s wrinkled face cracked in a smile at his nervouness, and for a moment he was merely Rawann’s father again, not the leader of the tribe. Then, with a confident shove to his back, Rawan was propelled out of the fasting hut into the village commons.

The beautiful Pandaweth, skinny and weak like him just a year earlier, now lush and strong, escorted him to the feast table. Into his ear she whispered, “Listen to the shaman’s words. They are subtle but important.”

The sweetness of her scent mingled with the spiced blood and the banquet, and Rawann’s head spun. Even the music of the tribe seemed to have a taste. He smiled suddenly, feeling confident that he would not fail. The tribe danced around him, and all senses blurred together in euphoria. *

Pandaweth helped him onto the stone seat at the head of the table, and then she slipped away, through the sparse crowd of the younger, Rawann’s siblings, friends, and cousins. Their ribs pressed out through their skin, their bellies strained with the bulge Rawann was so familiar with, though the elders assured him it was not the way their people had always been. They looked like him, not like the adults, whom hunger never bit.

His dizziness faded, and Rawann became aware of the food spread in front of him, more food than he had ever been allowed near before. A bowl of stewed beetles and mashed bone marrow; an entire bat, free from rot, coated in the grease he had always wished he could lick from the cookpots; a flayed eel over noodles of dried fungus; and a strange platter of crisp, curled strips of meat. He nearly broke then and started to eat, but the shaman’s voice sang out wordlessly amid the tribe’s music, and Rawann waited. Everyone grew silent.

“Rawann, child of Nusen and Toxell, today comes into manhood. He has chosen to undertake the Trial of Hunger, and so we commend him into its dangers with this parting feast.”

The shaman, Rawann’s father, circled the banquet table as he spoke, staring one by one in the faces of each member of the village. Some showed fear, others awe, a few disgust. As the shaman passed each, staring into his or her eyes, that villager’s face would shift to a look of profound longing.

“The great beast, Hunger, largest of the creatures of this island, roams beyond the wall, in the truly dead lands. All the adults here have faced it, and have seen that though the eternal famine we endure is painful, it can be survived. In the lands Hunger roams, however, nothing thrives. There is no life, only the endless heat of the burning sky, and the lonely song of the ocean. It takes bravery to look upon such bleakness, and Rawann’s test is to be as brave as his elders, as his parents, as his ancestors. With this final meal, we pray to bless Rawann with victory.”

A cheer went up from all the adults. The youths were more subdued. They knew none of the meal was for them, that they would have to wait for their chance to defeat Hunger.

“Not all who face Hunger pass this test,” the shaman continued, “but none who attempt it shall ever need to fear hunger again. The beast is a fearsome foe, and one we must forever contend with, but those who humble its bite are forever nourished and made healthy. This alone is how we can survive hunger’s presence.”

The shaman turned and kneeled beside Rawann, bowing his head and extending his hands, wrists forward.

“Rawann,” he asked, “are you brave?”

Rawann opened his mouth, a reply forming on his lips, and the cheers of his tribe drowned out his words. Again he smiled, confident.

Soon only a few of the adults remained, for the youths were not allowed to witness any more of the trial.

“Eat,” the shaman said, laughing at Rawann’s sudden timidity before the food.

He finally gave in, rapaciously finishing the beetle stew before he could even appreciate the exquisite skill that had gone into its creation. The assembled adults, all friends or family, laughed with good nature.

Pandaweth called out, “I guess you’ll be wanting a knife for your trial?”

He nodded back and kept eating. He wanted to ask what he needed to do for the trial, but he knew they would not tell him. He focused only on the food, sometimes feeling his eyes roll back in his head from the pleasure of eating. The others talked while Rawann ate – beetles, bat, and eel, but by then he felt the unfamiliar sensation of fullness in his stomach. He paused to savor in it, and a long moment passed.

Finally, he sighed and patted his belly, then looked to the last plate of unfamiliar meat. His father saw the movement and raised his hands. Immediately the assembled adults grew quiet, listening. When Rawann’s father spoke, it was again the shaman, his voice filled with pride.

“This is our body.”

The shaman pulled down his collar to reveal a fresh raw wound on his chest. Rawann looked around, and all the others were doing the same. Some of the older villagers had many scars across their chest, and the shaman had dozens, more than Rawann could count.

The shaman said, “Only by selflessness can we survive in this desolate land. Only by generosity can we have any meaning in this faminous life. Only by sacrifice can the stronger protect the weaker.

“Every adult of the tribe has given a slice of his or her flesh, has sacrificed willingly to strengthen you. Hunger cannot be killed. It can only be staved off by sacrifice. Eat, and have our bravery. This is our final blessing to you.”

The shaman, his father, bent and ran his fingers through Rawann’s hair. He whispered, “You will make us proud.”

Then, without another word, the adults left the village commons, all but Pandaweth. Rawann hesitated, waiting for her to speak, but she did not move. He could still smell her, the girl he had adored, now a woman waiting to guide him into his trial. Finally, almost like a concession, she gave a faint smile.

Rawann ate, carefully finishing each piece of meat, wondering who it had belonged to, conscious that this might be his last ever contact with them. When he was done, he looked back at Pandaweth. She smiled sincerely this time, and pulled down her collar to reveal a thin cut, just above her breasts.

Rawann started to speak, but Pandaweth raised a forestalling hand.

“Take these, and follow the shore east beyond the wall. If you survive, return and you will be met at the fence. There are things you will still need to learn, and your body may ache from the sudden fullness.”

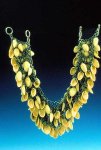

She handed him his weapons, then held out one last item, a sea shell covered with bright colors, trimmed in gold. *

“Wear this pin on your chest. It will keep you from needing to eat during the trial. You may be gone for several days, seeking Hunger, and there is no food at all beyond the wall. Do not lose it, for it will keep you safe from the heat of the daylit sky.”

She leaned close and put a hand over his belly, and the touch reminded him of the joy of being full. So intent was he on the feeling that he did not notice when she left him. All he knew was that day was coming, and that he was alone in his trial.

The fiery glow of the burning sky floated in the distant north, concealed by miles of clouds, but still casting a wretched, searing wind upon the island. It was day, and Rawann’s feet burned in the brown sands at the edge of the ocean. Heat pressed up between his toes as he sprinted, but the sight of the black wall carried him onward. He cast off his pants and sleeves, leaving only his shirt, his loincloth, his dagger, and the golden pin. They might burn behind him in the sand, but the thought did not worry him. If he failed on his trial, he would not need them. *

The wall stretched the length of the island, dozens of miles of stone covered in tar and oil, the only protection between Rawann’s people and the beast known as Hunger. All youths of the village were forbidden to cross the wall, or to even touch it. Skulls of old shamans lined the top of the wall, staring into the forbidden land.

Flesh raw from the heat but somehow not burning, Rawann scrambled up the blackened stones, his sprinting pace not slowing until he reached the top and could see beyond.

The line of the coast stretched out beyond his sight, obscured by waves of heat. Rock crackled and gasped steam, and a faint orange glow spread across the most distant land. The ground was bare of anything but ash and tainted water. What little life could survive behind the protection of the wall could never thrive here. There was only the movement of mist, tide, and heat. The land was death, illuminated by the red-gold glow of the great fiery rift in the distant north.

Rawann’s heart faltered, but he clenched the hilt of his knife and looked for a path. Beyond all this wasteland was the mountain, bleak and dark on the horizon. He knew he would find Hunger there.

Eventually night fell and the distant fires of the burning sky were dimmed by moonlight over the ocean, but Rawann ran onward. He felt something strange inside. It was not the pain of an empty stomach, nor the pleasant fullness of the previous evening’s banquet. He only felt nothing. His body seemed numb inside, a contrast to the pain without.

Exhaustion took him as day again neared, and he took refuge in pile of stones he fashioned into a crude cave, where he slept. When darkness fell, he ran again, always toward the mountain.

The third day passed, and Rawann survived the searing orange fields of fire that made him feel like a cooked strip of meat. He ran onward still, wondering what beast could suck the life from so much land. He had heard the tales of the old world, green and flowing with food, but now almost nothing would grow.

The others may have survived Hunger, he thought, but seeing this desolation, he wanted to defeat the beast. Maybe with Hunger dead, they would have a chance to find a life somewhat like that of the old world.

On dusk of the third day, Rawann climbed the mountain. He had long lost sight of shore, and his home had begun to fade from memory. He struggled through the night, scrambling up strange slick rocks, wandering blindly through clouds of cold mist. Often he thought he heard the distant beating of feet into stone, but as fast as he could chase, he could not catch the beast. The numbness inside him blended with the weariness of his mind, and finally he collapsed, and dreamed.

The mountainside was green, soft like cloth. He lay on his back, staring up to a blue sky, bright, but not painful to see. Tender wind blew across his face and stirred his hair, and a voice spoke to him.

Before I came to be, your people fled the burning sky, taking the mother deep beneath the earth. There, magic protected you and guided you, but the only element that gave its power freely was decay. Your people protected the mother, but despair strengthened, and you feared you had made a terrible mistake. Some wished to return to the land above, for your people knew not how to live in the land of darkness.

Before your people left, you spoke to the mother, then but a child herself. You asked her, dream to save us from our suffering. Dream to end this pain. But the mother’s sleep held only nightmares, and so was born Hunger. Incarnation of all your people’s fears, the beast was driven from the land below to the land of the burning sky. You followed it, and defeated it, but could never kill it, for you were too wise to free it.

Some of your people followed you, vowed to guard the beast and keep it from returning to the land below. You hoped to keep your people safe, but like the mother and her dreamborn son, you could only hope your descendants would be strong enough to accept their burden.

Wind gusted across Rawann, and he heard a sound from behind him, like a pained, heavy breath. Half-dreaming, half-awake, he sat up and spun to face the speaker. At first he saw a noble, peaceful creature, staring down at him with sorrowful black eyes. It stood on four legs, its heavy white coat stirring in the mountain gales. *

But then the dream began to fade, and hair seared away, curling black and streaking limply across the creature’s emaciated ribcage. Yellow blood seeped from its eyes, and its body spasmed, something twisting visibly in the intestines that pressed against its underbelly. It stood over Rawann on the blasted mountain landscape as the fires of the burning sky began to boil dew to searing steam.

“Please,” the creature said, its hollow voice cracking with an ageless thirst, “it gnaws at me. It burns me from within. It devours me and is never sated. Please, kill this hunger inside me.”

Rawann recoiled and kicked away, pulling his dagger and holding it forward to ward off the beast. The monster balked, and when its bleating voice tore through the air, it seemed as if the entire world was in pain. It tried to walk toward him, but staggered and fell to its knees. Jagged stone tore away fur and skin and revealed no flesh, nothing but bone beneath.

“Help me,” pleaded Hunger, helpless before him. “Let me devour you.”

Rawann felt a heave in his stomach, and something burned the inside of his throat, but he fought it down, focusing his will on the hilt of his knife. He trembled, then raised the blade. The creature would not trick him like it must have tricked the others. He knew what pain it had brought his tribe, and he would not let this creature live after coming so far to defeat it.

He had never killed anything before, but the beast’s body gave little resistance to his plunging blade. Bones snapped, flesh tore, and the creature wailed as it struggled to stand, but slowly, painfully, it slid to the ground. Its breath rattled out of its shattered skull, and then it moved no more. Rawann’s arms were covered in yellow and black bile, and he cast aside the dagger, leaving it and the beast’s corpse to whatever scavengers might some day come to this desolate mountain.

Something thrummed briefly around him, and the air felt heavy, wet and hard to breath, but then once more he felt nothing inside his body. He was satisfied, proud, but he cared not for his flesh. As he wandered down the mountainside he wondered if this is how he would feel from now on, detached from the physical world. He looked forward to it.

Three days later, at midnight, Rawann stood again at the top of the black wall.

Two torches illuminated the shaman and Pandaweth, standing on the shore. Rawann waited for them to approach him, anticipating whatever ceremony would formally make him an adult. He would not tell them he had slain Hunger, he decided, until he was more certain how they would react.

The shaman and Pandaweth met him at the top of the black wall, and his father embraced him.

“Rawann, my son. You have returned. Were you successful in your trial?”

The question seemed odd to Rawann. Why would he know if he had succeeded? Wasn’t it the shaman’s place to tell him?

Pandaweth pointed to Rawann’s belt. “He does not have his dagger.”

His father looked at him in confusion, then drew in a worried breath. Rawann stepped away, afraid he had made a horrible mistake. But then his father was the shaman again, staring into Rawann’s eyes. The old shaman spoke with despair.

“Oh no, child. You have failed.”

The shaman tore the pin from Rawann’s shirt, and the numbness left him in a writhing boil of pain, struggling within his belly. Rawann doubled over and cried out, clutching his stomach, trying to pull at whatever was devouring him from within.

Pandaweth cried out and looked away. “I’m sorry, Rawann.”

Rawann twisted on the ground, choking on his own blood. He looked up for his father, pleading, but saw only the shaman, watching his agony with dispassion.

“Rawann,” the shaman said, drawing a knife of his own, “Hunger cannot be killed. It is not a beast that must be fought, but a suffering that must be endured, and a pain that must be lessened by us however we can. The beast did not need your fury, boy. It needed your mercy.”

Rawann shrieked as a newborn Hunger tore through his intestines and stomach. As his vision blurred red, he saw the shaman, his father, cutting a strip of flesh from his own chest. As his ears ruptured from his own screams, he heard a whispered apology. As he lost all sense in his skin, he felt warm flesh brush his lips. And in his last moment, he tasted sweet flesh and blood, banishing his hunger to the endless darkness.

Flesh is weak. Spirit is eternal. And the food of the soul is mercy.

By Ryan Nock

Flesh is weak, the adults taught. Spirit is eternal, they insisted. One’s body is suffering until freedom, and Rawann believed that. But every adult had once been young, and all had undergone the Trial of Hunger. They appreciated that the weakness of flesh has its benefits, though they could no longer enjoy them.

The celebration cookfires filled the darkness of Rawann’s village with a joyous glow, but as his elders danced and sang for his rise to maturity, Rawann fought the pangs of his stomach.

“This night,” the shaman promised, “you shall hunger your last.”

The shaman smeared seasoned blood on his forehead, and Rawann nodded, hopefully.

This meal would bless him on his trial, and if he could survive it, the magic would sustain him for the rest of his life, as it did all the adults of his tribe. Food had been scarce all his life, and for countless generations before him, scarce since the scorching of the sky, scarce forever.

How the village had brought together foods of so many scents bewildered Rawann, frightened him. The shaman’s wrinkled face cracked in a smile at his nervouness, and for a moment he was merely Rawann’s father again, not the leader of the tribe. Then, with a confident shove to his back, Rawan was propelled out of the fasting hut into the village commons.

The beautiful Pandaweth, skinny and weak like him just a year earlier, now lush and strong, escorted him to the feast table. Into his ear she whispered, “Listen to the shaman’s words. They are subtle but important.”

The sweetness of her scent mingled with the spiced blood and the banquet, and Rawann’s head spun. Even the music of the tribe seemed to have a taste. He smiled suddenly, feeling confident that he would not fail. The tribe danced around him, and all senses blurred together in euphoria. *

Pandaweth helped him onto the stone seat at the head of the table, and then she slipped away, through the sparse crowd of the younger, Rawann’s siblings, friends, and cousins. Their ribs pressed out through their skin, their bellies strained with the bulge Rawann was so familiar with, though the elders assured him it was not the way their people had always been. They looked like him, not like the adults, whom hunger never bit.

His dizziness faded, and Rawann became aware of the food spread in front of him, more food than he had ever been allowed near before. A bowl of stewed beetles and mashed bone marrow; an entire bat, free from rot, coated in the grease he had always wished he could lick from the cookpots; a flayed eel over noodles of dried fungus; and a strange platter of crisp, curled strips of meat. He nearly broke then and started to eat, but the shaman’s voice sang out wordlessly amid the tribe’s music, and Rawann waited. Everyone grew silent.

“Rawann, child of Nusen and Toxell, today comes into manhood. He has chosen to undertake the Trial of Hunger, and so we commend him into its dangers with this parting feast.”

The shaman, Rawann’s father, circled the banquet table as he spoke, staring one by one in the faces of each member of the village. Some showed fear, others awe, a few disgust. As the shaman passed each, staring into his or her eyes, that villager’s face would shift to a look of profound longing.

“The great beast, Hunger, largest of the creatures of this island, roams beyond the wall, in the truly dead lands. All the adults here have faced it, and have seen that though the eternal famine we endure is painful, it can be survived. In the lands Hunger roams, however, nothing thrives. There is no life, only the endless heat of the burning sky, and the lonely song of the ocean. It takes bravery to look upon such bleakness, and Rawann’s test is to be as brave as his elders, as his parents, as his ancestors. With this final meal, we pray to bless Rawann with victory.”

A cheer went up from all the adults. The youths were more subdued. They knew none of the meal was for them, that they would have to wait for their chance to defeat Hunger.

“Not all who face Hunger pass this test,” the shaman continued, “but none who attempt it shall ever need to fear hunger again. The beast is a fearsome foe, and one we must forever contend with, but those who humble its bite are forever nourished and made healthy. This alone is how we can survive hunger’s presence.”

The shaman turned and kneeled beside Rawann, bowing his head and extending his hands, wrists forward.

“Rawann,” he asked, “are you brave?”

Rawann opened his mouth, a reply forming on his lips, and the cheers of his tribe drowned out his words. Again he smiled, confident.

***

Soon only a few of the adults remained, for the youths were not allowed to witness any more of the trial.

“Eat,” the shaman said, laughing at Rawann’s sudden timidity before the food.

He finally gave in, rapaciously finishing the beetle stew before he could even appreciate the exquisite skill that had gone into its creation. The assembled adults, all friends or family, laughed with good nature.

Pandaweth called out, “I guess you’ll be wanting a knife for your trial?”

He nodded back and kept eating. He wanted to ask what he needed to do for the trial, but he knew they would not tell him. He focused only on the food, sometimes feeling his eyes roll back in his head from the pleasure of eating. The others talked while Rawann ate – beetles, bat, and eel, but by then he felt the unfamiliar sensation of fullness in his stomach. He paused to savor in it, and a long moment passed.

Finally, he sighed and patted his belly, then looked to the last plate of unfamiliar meat. His father saw the movement and raised his hands. Immediately the assembled adults grew quiet, listening. When Rawann’s father spoke, it was again the shaman, his voice filled with pride.

“This is our body.”

The shaman pulled down his collar to reveal a fresh raw wound on his chest. Rawann looked around, and all the others were doing the same. Some of the older villagers had many scars across their chest, and the shaman had dozens, more than Rawann could count.

The shaman said, “Only by selflessness can we survive in this desolate land. Only by generosity can we have any meaning in this faminous life. Only by sacrifice can the stronger protect the weaker.

“Every adult of the tribe has given a slice of his or her flesh, has sacrificed willingly to strengthen you. Hunger cannot be killed. It can only be staved off by sacrifice. Eat, and have our bravery. This is our final blessing to you.”

The shaman, his father, bent and ran his fingers through Rawann’s hair. He whispered, “You will make us proud.”

Then, without another word, the adults left the village commons, all but Pandaweth. Rawann hesitated, waiting for her to speak, but she did not move. He could still smell her, the girl he had adored, now a woman waiting to guide him into his trial. Finally, almost like a concession, she gave a faint smile.

Rawann ate, carefully finishing each piece of meat, wondering who it had belonged to, conscious that this might be his last ever contact with them. When he was done, he looked back at Pandaweth. She smiled sincerely this time, and pulled down her collar to reveal a thin cut, just above her breasts.

Rawann started to speak, but Pandaweth raised a forestalling hand.

“Take these, and follow the shore east beyond the wall. If you survive, return and you will be met at the fence. There are things you will still need to learn, and your body may ache from the sudden fullness.”

She handed him his weapons, then held out one last item, a sea shell covered with bright colors, trimmed in gold. *

“Wear this pin on your chest. It will keep you from needing to eat during the trial. You may be gone for several days, seeking Hunger, and there is no food at all beyond the wall. Do not lose it, for it will keep you safe from the heat of the daylit sky.”

She leaned close and put a hand over his belly, and the touch reminded him of the joy of being full. So intent was he on the feeling that he did not notice when she left him. All he knew was that day was coming, and that he was alone in his trial.

***

The fiery glow of the burning sky floated in the distant north, concealed by miles of clouds, but still casting a wretched, searing wind upon the island. It was day, and Rawann’s feet burned in the brown sands at the edge of the ocean. Heat pressed up between his toes as he sprinted, but the sight of the black wall carried him onward. He cast off his pants and sleeves, leaving only his shirt, his loincloth, his dagger, and the golden pin. They might burn behind him in the sand, but the thought did not worry him. If he failed on his trial, he would not need them. *

The wall stretched the length of the island, dozens of miles of stone covered in tar and oil, the only protection between Rawann’s people and the beast known as Hunger. All youths of the village were forbidden to cross the wall, or to even touch it. Skulls of old shamans lined the top of the wall, staring into the forbidden land.

Flesh raw from the heat but somehow not burning, Rawann scrambled up the blackened stones, his sprinting pace not slowing until he reached the top and could see beyond.

The line of the coast stretched out beyond his sight, obscured by waves of heat. Rock crackled and gasped steam, and a faint orange glow spread across the most distant land. The ground was bare of anything but ash and tainted water. What little life could survive behind the protection of the wall could never thrive here. There was only the movement of mist, tide, and heat. The land was death, illuminated by the red-gold glow of the great fiery rift in the distant north.

Rawann’s heart faltered, but he clenched the hilt of his knife and looked for a path. Beyond all this wasteland was the mountain, bleak and dark on the horizon. He knew he would find Hunger there.

***

Eventually night fell and the distant fires of the burning sky were dimmed by moonlight over the ocean, but Rawann ran onward. He felt something strange inside. It was not the pain of an empty stomach, nor the pleasant fullness of the previous evening’s banquet. He only felt nothing. His body seemed numb inside, a contrast to the pain without.

Exhaustion took him as day again neared, and he took refuge in pile of stones he fashioned into a crude cave, where he slept. When darkness fell, he ran again, always toward the mountain.

The third day passed, and Rawann survived the searing orange fields of fire that made him feel like a cooked strip of meat. He ran onward still, wondering what beast could suck the life from so much land. He had heard the tales of the old world, green and flowing with food, but now almost nothing would grow.

The others may have survived Hunger, he thought, but seeing this desolation, he wanted to defeat the beast. Maybe with Hunger dead, they would have a chance to find a life somewhat like that of the old world.

On dusk of the third day, Rawann climbed the mountain. He had long lost sight of shore, and his home had begun to fade from memory. He struggled through the night, scrambling up strange slick rocks, wandering blindly through clouds of cold mist. Often he thought he heard the distant beating of feet into stone, but as fast as he could chase, he could not catch the beast. The numbness inside him blended with the weariness of his mind, and finally he collapsed, and dreamed.

***

The mountainside was green, soft like cloth. He lay on his back, staring up to a blue sky, bright, but not painful to see. Tender wind blew across his face and stirred his hair, and a voice spoke to him.

Before I came to be, your people fled the burning sky, taking the mother deep beneath the earth. There, magic protected you and guided you, but the only element that gave its power freely was decay. Your people protected the mother, but despair strengthened, and you feared you had made a terrible mistake. Some wished to return to the land above, for your people knew not how to live in the land of darkness.

Before your people left, you spoke to the mother, then but a child herself. You asked her, dream to save us from our suffering. Dream to end this pain. But the mother’s sleep held only nightmares, and so was born Hunger. Incarnation of all your people’s fears, the beast was driven from the land below to the land of the burning sky. You followed it, and defeated it, but could never kill it, for you were too wise to free it.

Some of your people followed you, vowed to guard the beast and keep it from returning to the land below. You hoped to keep your people safe, but like the mother and her dreamborn son, you could only hope your descendants would be strong enough to accept their burden.

Wind gusted across Rawann, and he heard a sound from behind him, like a pained, heavy breath. Half-dreaming, half-awake, he sat up and spun to face the speaker. At first he saw a noble, peaceful creature, staring down at him with sorrowful black eyes. It stood on four legs, its heavy white coat stirring in the mountain gales. *

But then the dream began to fade, and hair seared away, curling black and streaking limply across the creature’s emaciated ribcage. Yellow blood seeped from its eyes, and its body spasmed, something twisting visibly in the intestines that pressed against its underbelly. It stood over Rawann on the blasted mountain landscape as the fires of the burning sky began to boil dew to searing steam.

“Please,” the creature said, its hollow voice cracking with an ageless thirst, “it gnaws at me. It burns me from within. It devours me and is never sated. Please, kill this hunger inside me.”

Rawann recoiled and kicked away, pulling his dagger and holding it forward to ward off the beast. The monster balked, and when its bleating voice tore through the air, it seemed as if the entire world was in pain. It tried to walk toward him, but staggered and fell to its knees. Jagged stone tore away fur and skin and revealed no flesh, nothing but bone beneath.

“Help me,” pleaded Hunger, helpless before him. “Let me devour you.”

Rawann felt a heave in his stomach, and something burned the inside of his throat, but he fought it down, focusing his will on the hilt of his knife. He trembled, then raised the blade. The creature would not trick him like it must have tricked the others. He knew what pain it had brought his tribe, and he would not let this creature live after coming so far to defeat it.

He had never killed anything before, but the beast’s body gave little resistance to his plunging blade. Bones snapped, flesh tore, and the creature wailed as it struggled to stand, but slowly, painfully, it slid to the ground. Its breath rattled out of its shattered skull, and then it moved no more. Rawann’s arms were covered in yellow and black bile, and he cast aside the dagger, leaving it and the beast’s corpse to whatever scavengers might some day come to this desolate mountain.

Something thrummed briefly around him, and the air felt heavy, wet and hard to breath, but then once more he felt nothing inside his body. He was satisfied, proud, but he cared not for his flesh. As he wandered down the mountainside he wondered if this is how he would feel from now on, detached from the physical world. He looked forward to it.

***

Three days later, at midnight, Rawann stood again at the top of the black wall.

Two torches illuminated the shaman and Pandaweth, standing on the shore. Rawann waited for them to approach him, anticipating whatever ceremony would formally make him an adult. He would not tell them he had slain Hunger, he decided, until he was more certain how they would react.

The shaman and Pandaweth met him at the top of the black wall, and his father embraced him.

“Rawann, my son. You have returned. Were you successful in your trial?”

The question seemed odd to Rawann. Why would he know if he had succeeded? Wasn’t it the shaman’s place to tell him?

Pandaweth pointed to Rawann’s belt. “He does not have his dagger.”

His father looked at him in confusion, then drew in a worried breath. Rawann stepped away, afraid he had made a horrible mistake. But then his father was the shaman again, staring into Rawann’s eyes. The old shaman spoke with despair.

“Oh no, child. You have failed.”

The shaman tore the pin from Rawann’s shirt, and the numbness left him in a writhing boil of pain, struggling within his belly. Rawann doubled over and cried out, clutching his stomach, trying to pull at whatever was devouring him from within.

Pandaweth cried out and looked away. “I’m sorry, Rawann.”

Rawann twisted on the ground, choking on his own blood. He looked up for his father, pleading, but saw only the shaman, watching his agony with dispassion.

“Rawann,” the shaman said, drawing a knife of his own, “Hunger cannot be killed. It is not a beast that must be fought, but a suffering that must be endured, and a pain that must be lessened by us however we can. The beast did not need your fury, boy. It needed your mercy.”

Rawann shrieked as a newborn Hunger tore through his intestines and stomach. As his vision blurred red, he saw the shaman, his father, cutting a strip of flesh from his own chest. As his ears ruptured from his own screams, he heard a whispered apology. As he lost all sense in his skin, he felt warm flesh brush his lips. And in his last moment, he tasted sweet flesh and blood, banishing his hunger to the endless darkness.

***

Flesh is weak. Spirit is eternal. And the food of the soul is mercy.

alsih2o

First Post

Berandor said:Well, congrats Firelance, I guess.

You still want feedback on the story?

I would.

He/she earned it.

Berandor

lunatic

I just saw that the boards will be shut down for maintenance soon.

I don't feel good about publishing mythago's mail addy, so if you can't get on the boards to post your story, and don't know her address, you can send the story to

(a classified e-mail address, as the threat has gone past). I'll keep an eye on the timestamp, too

I hope Eluvan reads this in time

Feedback for firelance will follow.

I don't feel good about publishing mythago's mail addy, so if you can't get on the boards to post your story, and don't know her address, you can send the story to

(a classified e-mail address, as the threat has gone past). I'll keep an eye on the timestamp, too

I hope Eluvan reads this in time

Feedback for firelance will follow.

Last edited:

Berandor

lunatic

Firelance, here are my preliminary comments on your story. At least you're now the first to be judged (I know, that's a lame benefit).

I don't think posting them should be a problem, even without mythago's agreement.

Firelance, "The Gnomish Word for Word"

You get me at the first sentence. "Someone had stolen the Quill of Aureon." Who? What? Tell me!

What follows is a nice little story about an insane death-loving elf and the gnomish paladin that pursues him.

"But someone had stolen the Quill of Aureon anyway" made me smile. Very nice. The same with Zilan feeling a little annoyed at his brother for disallowing the enchanting of Zilan's lance. Cute touch.

I wasn't too clear about the world you have your heroes inhabit, because most comments and titles are quite contemporary, whereas the background seems more like a fantastic D&D world. So, I can't really accuse you of using too modern a language, but I sure suspect it.

I was also not too clear on the significance of the history book that got stolen from the library. Why did the elf need it?

I enjoyed the sign language you made up. That was a good touch, even if the symbol for "bridge" was ubiquitous. Also a humorous explanation for the gnomish enthusiasm for a written alphabet.

In all, the story really shines in its humor; it's a fine little quirky tale you weave. On the other hand, most conflict is glossed over or ended in a quite convenient manner. Combined with the humor, there's not much tension in your tale, it just flows along merrily. Everything happens just because it does, and there's never really a question to the eventual outcome.

A good example is when the elf casts Bagiby's hand (or something like it). He simply casts the spell, and Zilan doesn't do anything to stop him. Then, he's grabbed by the hand, but doesn't really struggle. Instead, he comments "there's not much I could do against it" when the eld draws his blood. That's a little... bloodless for my taste. (And how come the elf knew Zilan's name?)

In the mirror cabinet, when the heroes meet the skeletons, howe come the skeletons don't give of a reflection the heroes might notice. And what exactly happens to the guildmaster? After the Allip is gone, the guildmaster is, as well.

What I really liked was your description of the bard. The calm voice, the boring lecture (funny, yet contemporary "comparative religion seminary"), a very fun and funny approach!

Still, your protagonists remain quite hard to know. We're shown that Zilan knows a lot about words and vocabulary. But we're not told how he knows. In fact, we don't really get to know a lot about him, let alone Amelia. (and from a D&D perspective, how come the bard knows less about gnomish history than a paladin? )

)

You bring up points as they are needed; for example, it would have been nice to know beforehand that the paladin has a waraxe and at least one throwing axe, so it doesn't look like "I need a throwing axe, I'm gonna write one in".

And the final paragraph runs close to being worse than an afternoon special.

"You should do your homeworkd properly" - ugh.

Fortunately, you still end on a high note. "Trust me, I'm a paladin." is a *great* quote!

All in all, a fast-paced fun story, and a D&D-story to boot (we don't often have that!). Thank you very much, Firelance.

THE PICS:

The Quill-Thingy

-I don't really know what that's supposed to be, myself, so I accept the rotten quill at face value. The quill starts the story off and ends up being quite important for the ritual. It also fits thematically into the whole story; a good use.

The girl in the mirror

(doesn't she look like Sarah Michelle Gellar? Or is that just me?) Buffy... er, Amelia is the hero's sidekick, and her use of bardic "music" is one of the funnier ones I've read. Still, she remains fairly lifeless even after being instilled with positive energy by Zilan.

The sign

Now, I was dreading the sign in a "fantasy" story, but it together with the bridge helped you sell the story to me as being set in a more contemporary setting. And your explanation of the sign is very funny! Swiftcats/cheetahs, indeed!

The Bridge

Well, aside from the ever-appearing symbol in gnomish sign language, the bridge is the setting of the final conflict. Here, it really pays off that gnomish signs are so similar, as the elf can easily use the bridge to strengthen his ritual.

All in all, your pictures are used competently. I forgive the weaker sign for the funny explanation you give us, and I wish you'd have given us more about Amelia.

JUDGEMENT

The strong parts of your story is the humor and the inventiveness of it all. On the other hand, the story lacks details and descritpion, so we neither identify with the characters very much nor do we feel tension as much as would be possible. The idea certainly merits a story, but it could use being fleshed out some more.

A promising start-off, Firelance, and I'm really looking forward to your next entry.

Note: Even though it wasn't necessary, I somewhat copied the format of my other judgement for consistency.

I don't think posting them should be a problem, even without mythago's agreement.

Firelance, "The Gnomish Word for Word"

You get me at the first sentence. "Someone had stolen the Quill of Aureon." Who? What? Tell me!

What follows is a nice little story about an insane death-loving elf and the gnomish paladin that pursues him.

"But someone had stolen the Quill of Aureon anyway" made me smile. Very nice. The same with Zilan feeling a little annoyed at his brother for disallowing the enchanting of Zilan's lance. Cute touch.

I wasn't too clear about the world you have your heroes inhabit, because most comments and titles are quite contemporary, whereas the background seems more like a fantastic D&D world. So, I can't really accuse you of using too modern a language, but I sure suspect it.

I was also not too clear on the significance of the history book that got stolen from the library. Why did the elf need it?

I enjoyed the sign language you made up. That was a good touch, even if the symbol for "bridge" was ubiquitous. Also a humorous explanation for the gnomish enthusiasm for a written alphabet.

In all, the story really shines in its humor; it's a fine little quirky tale you weave. On the other hand, most conflict is glossed over or ended in a quite convenient manner. Combined with the humor, there's not much tension in your tale, it just flows along merrily. Everything happens just because it does, and there's never really a question to the eventual outcome.

A good example is when the elf casts Bagiby's hand (or something like it). He simply casts the spell, and Zilan doesn't do anything to stop him. Then, he's grabbed by the hand, but doesn't really struggle. Instead, he comments "there's not much I could do against it" when the eld draws his blood. That's a little... bloodless for my taste. (And how come the elf knew Zilan's name?)

In the mirror cabinet, when the heroes meet the skeletons, howe come the skeletons don't give of a reflection the heroes might notice. And what exactly happens to the guildmaster? After the Allip is gone, the guildmaster is, as well.

What I really liked was your description of the bard. The calm voice, the boring lecture (funny, yet contemporary "comparative religion seminary"), a very fun and funny approach!

Still, your protagonists remain quite hard to know. We're shown that Zilan knows a lot about words and vocabulary. But we're not told how he knows. In fact, we don't really get to know a lot about him, let alone Amelia. (and from a D&D perspective, how come the bard knows less about gnomish history than a paladin?

You bring up points as they are needed; for example, it would have been nice to know beforehand that the paladin has a waraxe and at least one throwing axe, so it doesn't look like "I need a throwing axe, I'm gonna write one in".

And the final paragraph runs close to being worse than an afternoon special.

"You should do your homeworkd properly" - ugh.

Fortunately, you still end on a high note. "Trust me, I'm a paladin." is a *great* quote!

All in all, a fast-paced fun story, and a D&D-story to boot (we don't often have that!). Thank you very much, Firelance.

THE PICS:

The Quill-Thingy

-I don't really know what that's supposed to be, myself, so I accept the rotten quill at face value. The quill starts the story off and ends up being quite important for the ritual. It also fits thematically into the whole story; a good use.

The girl in the mirror

(doesn't she look like Sarah Michelle Gellar? Or is that just me?) Buffy... er, Amelia is the hero's sidekick, and her use of bardic "music" is one of the funnier ones I've read. Still, she remains fairly lifeless even after being instilled with positive energy by Zilan.

The sign

Now, I was dreading the sign in a "fantasy" story, but it together with the bridge helped you sell the story to me as being set in a more contemporary setting. And your explanation of the sign is very funny! Swiftcats/cheetahs, indeed!

The Bridge

Well, aside from the ever-appearing symbol in gnomish sign language, the bridge is the setting of the final conflict. Here, it really pays off that gnomish signs are so similar, as the elf can easily use the bridge to strengthen his ritual.

All in all, your pictures are used competently. I forgive the weaker sign for the funny explanation you give us, and I wish you'd have given us more about Amelia.

JUDGEMENT

The strong parts of your story is the humor and the inventiveness of it all. On the other hand, the story lacks details and descritpion, so we neither identify with the characters very much nor do we feel tension as much as would be possible. The idea certainly merits a story, but it could use being fleshed out some more.

A promising start-off, Firelance, and I'm really looking forward to your next entry.

Note: Even though it wasn't necessary, I somewhat copied the format of my other judgement for consistency.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 187

- Views

- 16K

- Replies

- 180

- Views

- 29K

Recent & Upcoming Releases

-

June 16 2026 -

June 16 2026 -

September 16 2026

Arcana Unleashed(Dungeons & Dragons)

Rulebook featuring "high magic" options, including a host of new spells.

Replies (45) -

September 16 2026 -

October 1 2026 -

October 6 2026 -

January 1 2027